Dental anxiety has been a topic of scientific attention since the 1970’s1. The term refers to the specific reaction of patients to dental treatment-related stress2. Dental fear, however, is explained by the feeling that arises in connection with specifically occurring impulses3, for instance the sound of drills or the smell of dental practices. Dental fear and anxiety (DFA) create challenges in oral healthcare not only for patients’ well-being and health but also for the dental care team4,5. The global prevalence of DFA is estimated at 15.3% with any DFA, 12.4% with high DFA, and 3.3% with severe DFA whereby mostly women seem to be affected3. Treating patients with DFA may result in increased time required for treatment or a stressful experience for both patients and dentists due to the anxiety and corresponding reactions5. Moreover, research indicates that DFA increases the pain perception of patients during treatment6. The negative effects of DFA might also intensify in a vicious cycle of anxiety7,8. Hence, dealing with DFA is considered a challenging task for dentists and dental staff9.

Based on these findings, the need for strategies to prevent and treat DFA is apparent and currently reflected in several approaches: pharmacological management of patients with a high level of DFA is well established10. Also, non-pharmacological techniques are frequently used, such as distraction, relaxation, providing information about the treatment and establishing a trusting relationship7. This also includes methods used in complementary and integrative medicine (CIM) to reduce stress and anxiety, and enhance general well-being, such as progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery, hypnosis, music therapy, and acupuncture5,7,11. The specific use of stress-reducing essential oils via inhalation, also known as aromatherapy, is also considered to be effective at reducing anxiety and pain in health related research12 including pain experienced during dental care5,6,7,11,13. Overall, applying aromatherapy with essential oils has the advantage of potentially being beneficial to all dental patients, regardless of their DFA level.

Aromatherapy

Essential oils are “mixture[s] of highly reactive, volatile, mostly fragrant chemical compounds”14 (quote translated by JC) extracted from plant components such as flowers, peels, resins, wood, bark, and roots. Under the term aromatherapy, essential oils are used mostly via inhalation and/or percutaneously15 for health promotion and disease relief as a supportive treatment approach in health related contexts16. The complex composition and the multitude of ingredients of essential oils are considered the basis for the potential of aromatherapy for health and well-being. The synergistic effects are assumed to go beyond the effects of the individual ingredients15,17,18. In addition, there are indications that a blend of different essential oils could enhance positive effects further19 while minimizing risks14,20.

According to current knowledge, the effects of essential oils are explained by two different modes of action/principles: psychological and pharmacological21,22. The psychological principle refers to individual and culturally shaped experiences associated with an odor that lead to subjective reactions. Thus, the same essential oil can trigger completely different reactions in different people. The pharmacological mechanism, on the other hand, is based on the specific composition of the essential oils and the affinity of its components to certain receptors. This is accompanied by a specific dose–response relationship and a substance specificity that is independent of cognitive control mechanisms. It can be assumed that in aromatherapy allocated through inhalation (e.g., via room vaporization), the psychological mechanisms of action predominate22,23. Accordingly, the explanations of the biological mechanism underlying the specific anxiolytic effect of essential oils have not been conclusively clarified12. Explanatory models invoke, for example, the influence of essential oil components on neurotrophic factors, the endocrine system, and neurogenesis19. Another assumption relates to the hypothesis that a subjectively positive association with odors could have a positive influence on emotions and thus an alleviating effect on acute anxiety22,24.

Despite the growing conviction that aromatherapy has the potential to reduce DFA, and pain, and to enhance the well-being of dental patients5, evidence underscoring these effects is still limited11. Some reasons can be related to the specific characteristics of the research field: Comparability is hampered because of differences in, for instance, essential oils used, context of application, and sample size. Moreover, transparency regarding the information about the essential oils used (e.g., manufacture, botanical names of the ingredients, composition), the devices for vaporizing, and the contextual conditions of the essential oil application (e.g., odor intensity, characteristics of the premises) is not always provided23,25. Furthermore, although the number of reviews on aromatherapy as an intervention against DFA5,6,7,11,13 suggests growing research activity on the topic, research gaps can be identified. For instance, no research about aromatherapy limiting DFA has considered the relevance of individual reactions on smell, and in all studies, only singular essential oils and no essential oil blends were used to our knowledge.

Research objective and design-shaping context

Subsequently, this study aimed to investigate the efficacy of aromatherapy on the acute state of anxiety and pain at the dentist, considering the psychological mechanism of action in terms of culturally shaped olfactory experiences in the study design.

Taking the psychological mechanism of action of essential oils into account, especially regarding the association of memories and cultural imprints with odor, essential oils used should meet two requirements. (1) They should cause physical relaxation given their pharmacological properties, and (2) they should be associated with relaxation and well-being by the greatest possible number of people to create a similar psychological effect. In many different cultures, the scent of forests is associated with relaxation, positive connotations, and memories. Associations with forests often coincide with idealized concepts of peacefulness, stillness, and closeness to nature, and are frequently closely linked to positive emotions and moods. This corresponds to the positive effect of the forest on the body and mind as shown by the multitude of scientific reviews on forest bathing26,27,28,29, forest therapy30, and nature therapy31. Nature-therapeutic approaches are also receiving increasing attention in the public presentation as health-promoting, preventing concepts.

Accordingly, and in line with the psychological effects of olfactory stimuli, it can be hypothesized that the scent of forest is associated with relaxation and may therefore have stress and anxiety-reducing effects in many people. Given this background, four different essential oils resp. oil blends were selected after consultation of professional aromatherapists from the company Primavera® for investigation regarding their anxiety-relieving effects in the dentistry setting: “Orange”, “Zirbelkiefer” (Swiss Pine), “Waldspaziergang” (Forest Walk), and “Gute Laune” (Good Mood). Rationales for the selection of essential oils and detailed information about their characteristics—orientated on the TREATS checklist (transparent reporting for essential oil & aroma therapeutic studies)32—are summarized in Table 1.

Based on the outlined considerations, the study investigated the following hypotheses:

-

1. Aromatherapy with stress reducing essential oils evaporated in dental practices has an alleviating effect on patients’ feelings of acute anxiety.

-

2. The anxiety reducing effect of the essential-oil blends (Good Mood and Forest Walk) is stronger than that of the corresponding mono oils (Orange and Swiss Pine).

-

3. The forest associated essential oil (Swiss Pine) and the corresponding blend (Forest Walk) show the strongest effect compared to the essential oil Orange and the corresponding blend Good Mood.

-

4. The anxiolytic effect of the essential oil vaporization corresponds to a lower subjective pain perception in patients during the treatment.

Material and methods

A controlled, single-blinded, cluster-randomized design with four dental practices in Berlin was conducted between October and December 2022. The study was registered in the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS00027233, 16/11/2021) and followed the CONSORT reporting guidelines45.

Study design

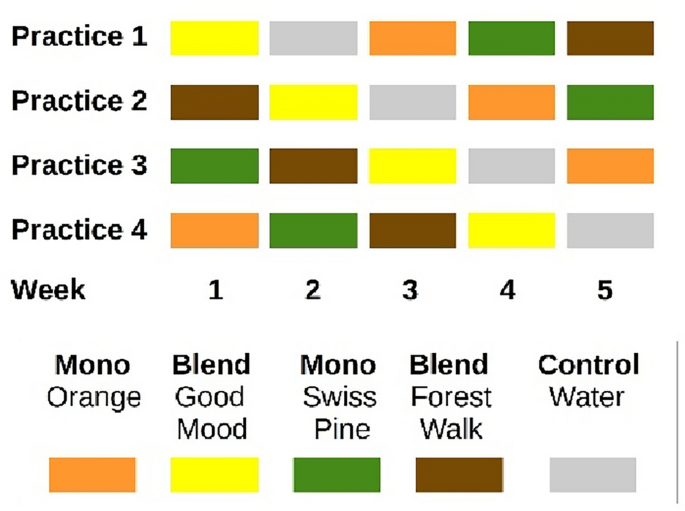

In the selection process of dental practices, care was taken to ensure a wide variation in size, practice layout, location, and patient clientele in order to target and collect data on a broad group sample. Each of the five conditions (Orange, Swiss Pine, Forest Walk, Good Mood, and water as a control, cf. Figure 1 and Table 1) was tested in each practice for 1 week for data collection. The order of five conditions was put into a random order and each practice started with a different condition also randomized (using randomization routines provided in Python). This ensured a balanced design wherein each week, each practice utilized a different essential oil. (cf. Figure 1). In that way, patients were allocated to their intervention group based on the week of their appointment. Data collection took place in all four practices for a total of 5 weeks between October 10th and November 11th, 2022. However, it was extended by an additional 5 weeks in practice 1 and by 1 week in practice 3 in order to reach the calculated sample size.

Essential oil vaporization was performed in both the waiting areas and treatment rooms. For the waiting rooms, one large app-controlled vaporizer (HAAL ROSA) was used in each practice. Settings were adjusted to a medium diffusion intensity that was adapted to size and layout of the respective premises. For the individual treatment rooms, the smaller manual diffusers Feel Happy (Primavera®) were used and filled with 4–6 drops of essential oils (for medium diffusion intensity, depending on the size of the respective treatment room, and per the intensity of diffusion in the waiting areas) and water (maximum capacity) three times a day, approximately every 3 h. The manual diffusers were cleaned with water daily before closing time. The app-controlled vaporizer was cleaned once a week on Friday just before closing time and filled with the essential oil for the following week. During the control week, all devices were switched off. The staff from all participating dental practices was instructed and trained by one member of the research team (JC) on the safe use of the equipment and the essential oils. In addition, the staff received detailed manuals on how to use the devices. The research team could be contacted at any time if questions arose.

Sample size calculation

The required number of patients was calculated prospectively on the following basis: with a large effect size (0.7) (based on the published study populations of Lehrner et al., Zabirunnisa et al.9,34), alpha* = 0.013 (three patient groups), beta = 0.20 (power = 80%), ICC = 0.01, 47 patients* should be included per patient group and condition (essential oil and control groups), i.e., 705 patients* where planned in total (G*Power 3.1), i.e. 750 allowing for a dropout of 6%.

Sample description

Adult patients at the four dental practices between 18 and 65 years during the data collection period who were willing were eligible to participate in the study. Patient recruitment (distribution of study information, obtaining informed consent, distribution, and collection of questionnaires) was undertaken by the individual dental practice staff. A cover story was initially used to blind the patients from the true study objective of testing essential oil vaporization effects on state anxiety and the perception of pain. The cover story described the subject of the study as an investigation of the effect of anxiety on pain perception, as was similarly done in a study by Lehrner et al.33.

Patients’ reasons for the visit to the dentist were clustered into three groups, “routine examination”, “acute pain” and “planned intervention”, since it can be assumed that the severity of anxiety also might depend on the planned treatment. Sociodemographic data was collected on the age range (18–30 years, 31–45, or 46–65) and gender (diverse, female, male).

Data collection

The primary outcome measure for the study was the acute anxiety of the dental patients. In addition, three secondary outcomes were collected on trait anxiety, dental anxiety, and subjective pain perception during treatment. Acute and trait anxiety were measured with the state-trait-anxiety inventory (STAI). The STAI is a questionnaire that separately assesses state anxiety (= acute anxiety, STAI-S) and trait anxiety (= general disposition to anxiety, STAI-T) with 20 separate items using the most current, validated, and widely distributed version published in 1983 by Charles Spielberger. The German version used in the study AROMA_dent was developed and validated in 198146. Participants were grouped by their score according to the trait anxiety scale with respect to a cutoff-score of ≤ vs > 42 as an average between the published cutoff-scores for STAI of 40 and 4447,48,49.

The second secondary outcome, dental anxiety, was collected with the Kleinknecht’s dental fear survey (KDFS)50. The questionnaire was translated into a German version. The translation process took place in accordance with relevant guidelines51.

The third and final secondary outcome of the patient’s subjective pain perception during treatment was collected by a numeric rating scale (NRS) ranging from 0 (= no pain) to 10 (= strongest pain imaginable).

The data was collected at two time points: the measurement of the data on anxiety by means of STAI and KDFS took place directly after the registration of the patients at the reception, allowing exposure to the essential oils for a short time (assumed 10–20 min) from the time they entered the practice until they completed the questionnaires, with documentation of acute anxiety with the STAI-S planned at the end of the questionnaire. The subjective pain perception of the patients was collected directly after the treatment by the dentist.

Data analysis

The data was analyzed separately for each of the reason for visit patient groups, i.e., for patients visiting the practice for acute pain, for control or for planned procedures. For the primary outcome, acute anxiety prior to dental treatment was measured and compared between the four essential-oil conditions and the control condition. Independent ANCOVAs were calculated to estimate the contribution of the confounders: age, gender, trait anxiety and practice. For the secondary outcomes, the comparison between control condition and essential oil treatments was repeated regarding the outcome pain, and STAI-S was compared between blended essential oils vs. mono essential oils as well as forest-associated essential oils (Swiss Pine, Forest Walk) vs. fruit-associated essential-oils (Orange, Good Mood).

Only the three tests (for the three patient groups) for the primary endpoint were tested in confirmatory fashion using an adjusted alpha * of 0.0167. All of the other tests were assessed on an exploratory level only (against an unadjusted alpha = 0.05). Data was analyzed using custom-written python (version 3.9) routines and the statistical packages Statsmodels and Pingouin.

Safety and adverse events

Since the patients were partially blinded by the cover story and the actual intervention (= essential oil vaporization in the dental practices) was undisclosed, the staff was asked to forward complaints expressed in relation to the odor in the dental practice to the research team.

Ethics approval

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Charité—Universitätsmedizin Berlin on August 20th, 2021 (EA2/197/21).