Melissa Connelly watched as a nurse coaxed her wife, Kim, awake following her colonoscopy on November 4, 2020. Drowsy from the anesthesia, Kim couldn’t hold a can of ginger ale to her lips, so Melissa did it for her.

The nurse explained to Melissa that the procedure had gone well, but Kim would feel a bit woozy. Before heading home, Kim, who’s an ICU nurse, was able to ask about the drugs she’d been given. The nurse told her they had administered 5 milligrams of the sedative Versed and 100 micrograms of the narcotic painkiller Fentanyl.

Nearly one month later, on December 2, 2020, Melissa, who’s Black, was admitted to the same major Midwest hospital, this time for her own colonoscopy. She had the same doctor and support staff as Kim, who’s white and Asian.

Once the anesthesia was administered, Melissa says she was still conscious, though “slightly loopy.” And for a while, she watched her procedure play out on the monitor. She knew it wasn’t unusual to remain slightly alert and experience some sensation following sedation, so she wasn’t worried at first. “However, at some point, it hurt to the point that I audibly cried out, ‘Ow, that hurts. I can feel that.’” In response, Melissa was advised to “breathe in through your nose and out through your mouth.” She was shocked. “I remember thinking, ‘You’ve got to be kidding me. That’s the best advice you have?’”

When the procedure was over and Kim came to meet Melissa, Kim remarked, “You’re so awake!” And when Kim noticed Melissa was able to hold her own apple juice, Kim asked the nurses, “How much [sedation and pain relief] did she get?” The nurse replied, 3 milligrams of Versed and 50 micrograms of Fentanyl. Neither woman had a certified registered nurse anesthetist on their surgical teams, meaning it was the doctor himself who decided what their respective doses of anesthesia would be.

At the time, Melissa, who’s 37, outweighed a then-34-year-old Kim by 20 pounds. She’s also 2 1/2 inches taller, and, like Kim, has no underlying health conditions. Still, Melissa received only a half of the drugs her wife did. And when she felt pain, Melissa was expected to manage it on her own.

“I couldn’t have done a better ‘lab experiment’ than to have two identical scenarios and such a different level of treatment,” Melissa says.

Numerous studies investigating racial disparities in healthcare indicate that Black people’s pain is often perceived to be less severe than that of their non-Black counterparts.

“Racial disparities in healthcare, both access to care and quality of care, are the product of systemic racism and individual prejudice,” says Sophie Trawalter, PhD, associate professor of public policy and psychology at University of Virginia, whose research focuses on social diversity. The evidence is compelling, she says, and speaks for itself.

Racism In Science

One such study Trawalter worked on investigated the role of unconscious bias in a sample of 222 soon-to-be healthcare professionals. Trawalter and fellow researchers found that about 50 percent of medical students and residents attribute higher pain tolerance to Black patients compared to white patients. These students falsely believed Black people have less sensitive nerve endings, thicker skin, or stronger immune systems so therefore would require less invasive pain care than white people. As a result, residents and medical students “made less accurate treatment recommendations” for Black patients, according to the study published in 2016.

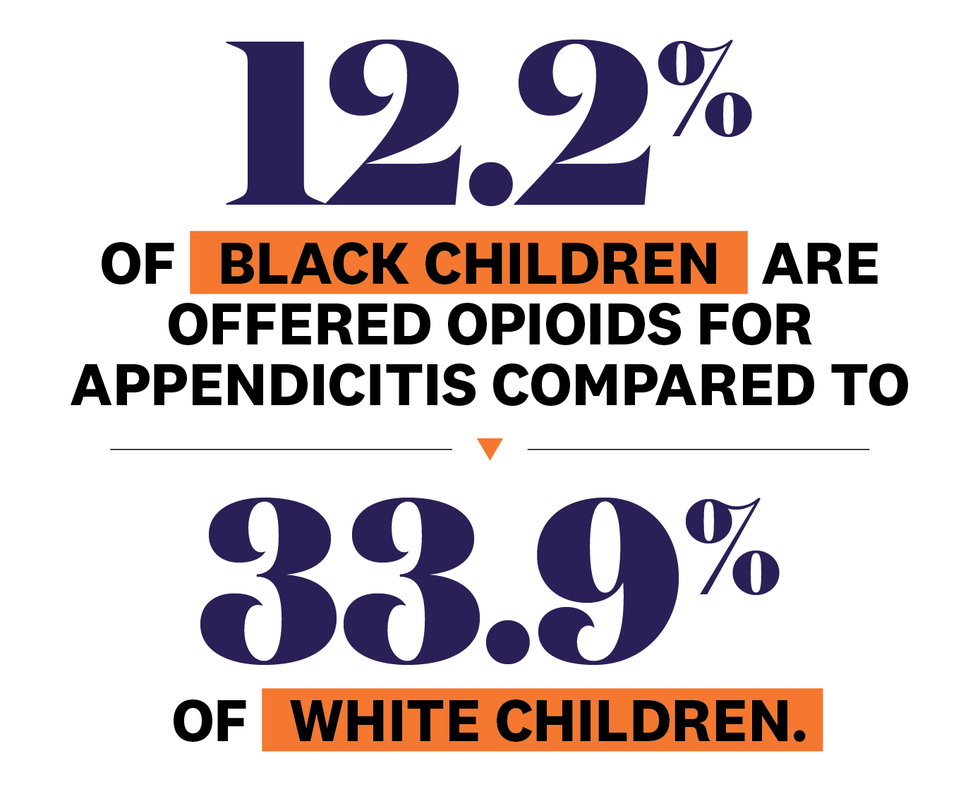

Black children are also significantly less likely to receive pain medication for appendicitis compared to white children, according to a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association Pediatrics in 2015. Only 12.2 percent of Black children were offered opioids, compared to 33.9 percent of white children. And when they described their pain as moderate, Black children were less likely to receive any pain medication at all.

These misconceptions are ingrained in people at a young age, too. Researchers who asked Black and white children to rate each other’s pain determined they’d adopted a “weak racial bias” by 7 years old and a “strong and reliable” bias by 10 years old.

A 2014 study asked participants to select whether they associated superhuman characteristics, including skin capable of withstanding the burn of hot coals and the ability to suppress hunger and thirst, with Black or white people. Results, published in Social Psychological and Personality Science, showed white participants typically “superhumanized” and attributed power capacities to Black people in order to justify beliefs that they’re inherently more resilient when hurt. Something, Trawalter says, is the result of the dehumanization of the Black community.

History Of Harm

The myth that there are significant biological differences between Black and white people has been prevalent in the United States for centuries.

In 1932, the Tuskegee Institute promised Black men free medical care to take part in a medical study. But in reality, doctors weren’t actually treating them at all. Instead, they were using the men to track the progression of untreated syphilis—even after a cure was discovered. When the researchers were found out, the study wasn’t shut down until 1972. And by then, a number of men went blind, deaf, became mentally ill, or died.

But Tuskegee isn’t where this legacy starts. Judgments about Black pain predate that. In fact, they predate the United States, says Carolyn Roberts, PhD, assistant professor and medical historian at the department of African American studies at Yale University.

“These ideas began to circulate when Europeans first got to the African continent, and they begin writing about their observations,” Roberts says. During the 15th century, Black people were perceived to be “coarse” and “savage,” unable to “express themselves in ways that were legible from a Eurocentric framework.” So, when they noticed African women returning to work after childbirth rather than keeping to the home, colonizers assumed Black people must not have felt pain at all.

By the 18th century in the United States, Roberts explains, figures including Thomas Jefferson built upon these theories and presented them as fact to justify slavery. In his “Notes On The State of Virginia” published in 1785, Jefferson writes about enslaved people: “Their griefs are transient.” Not only were they capable of enduring the physical labor and abuses of slavery without discomfort, but Black people, Jefferson characterized, were also incapable of internalizing the distress that comes with tragedy and brutality.

“Eventually, the use of the Black body in this particular way becomes layered with violence,” Roberts explains, speaking to when enslaved people were made to participate in the medical experiments that shaped anatomy, pathology, and obstetrics.

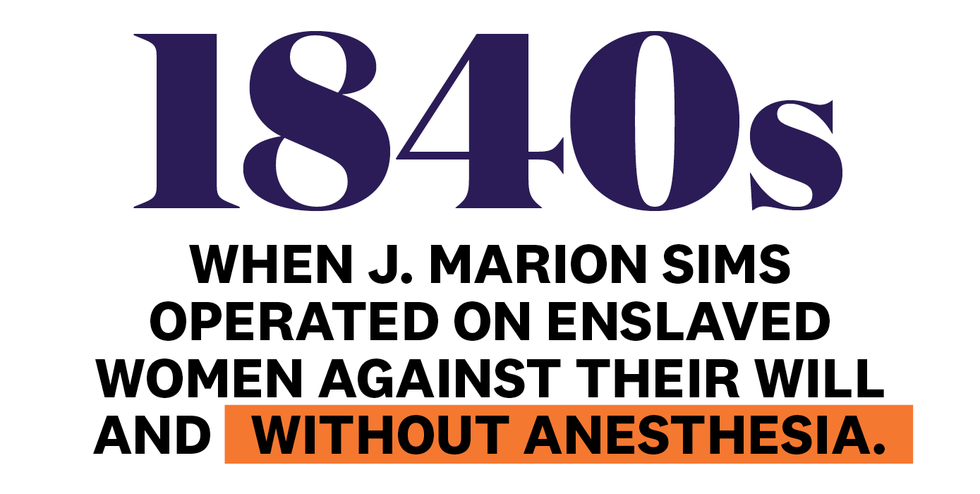

Take J. Marion Sims. He developed the surgical technique to repair vesicovaginal fistulas, a condition in which urine passes through an opening in the bladder wall and leaks out of the vagina. Before he mastered it, however, he tested various procedures on enslaved women—three of whom are known as the Mothers of Gynecology—against their will and without anesthesia during the 1840s. After repeatedly operating on Black women—as many as 30 times on one in particular—Sims discovered sutures made of silver were the answer because of their antimicrobial properties. The procedure perfected, he performed it on willing white women—only they got anesthesia, says Roberts.

Sims was just one of many who experimented on enslaved people. Following the Civil War during segregation, exploitative practices continued to downplay Black people’s physical and the emotional pain. When Henrietta Lacks, a poor tobacco farmer, went to Johns Hopkins Hospital in 1951 to treat a tumor, a doctor collected her cells without her knowledge or consent.

Lacks died later that same year, but to this day, her cells are being used in biomedical research. Because of an unusually active enzyme called telomerase, they have a unique capacity to survive and reproduce indefinitely. Her cells have been used to develop the polio vaccine, in-vitro fertilization, and most recently, for COVID-19 research.

For decades, Lacks’ family never knew her cells had been taken. They had no say over what was done with the tissue harvested from Lacks’ body, nor did they see any of the compensation the biomedical companies were given.

Medical segregation was formalized when The Hill-Burton Act of 1946 passed and used federal funds to improve healthcare facilities around the country. “The Act explicitly permitted racially exclusionary care and codified hospitals as ‘separate but equal.’ Additionally, the distribution of funds favored white hospitals,” adds Roberts. It wasn’t until the 1970s, years after the 1964 Civil Rights Act, that hospitals finally integrated—on paper, says Roberts.

Decades of experimentation and segregation didn’t usher in a wave of new initiatives to protect Black lives. On the contrary, the past has only served as the template for the present. “Some ideas have managed to endure across the centuries,” Roberts says. Long-held assumptions that pain doesn’t make Black people vulnerable has become the very thing that puts them at risk. Associations baked into our culture that paint Black people as hysterical, aggressive, and angry take up space in medical centers, says Roberts. And so today, though she’s treated in the same facility and has access to the same doctors, the pain management offered to Melissa Connelly and other Black Americans remains demonstrably different.

It doesn’t take a medical historian to know that, as a Black person, we have reason to be mistrustful of a disparate medical system. The lessons from the past are compounded now more than ever and have informed our worldview. The underestimation of our pain is inextricably linked to the notion that we’re disposable—abused and killed by law enforcement, dying of COVID-19 at higher rates, dying from childbirth at higher rates, and disproportionately incarcerated. And so, as happens in so many aspects of our lives, the onus falls on Black people to ensure we make it out alive. It’s on the people who are hurting to advocate for the very care we deserved all along.

How To Advocate For Yourself In An Emergency

Self-advocacy can take on a few forms, says Adaira Landry, MD, MEd, an emergency medicine physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School. First, she says, it’s important that you describe your situation in detail. Tell the medical staff how you got hurt, what your symptoms are, and how long you’ve been in pain. You might even write it down before you get to the doctor’s office or emergency room, so you don’t have to recall it on the spot.

➊ Be as specific as possible.

➔ Given the nature of the job, health professionals don’t have much time to get to know their patients, says Lisa A. Cooper, MD, MPH, director at Johns Hopkins Center for Health Equity and author of the forthcoming book Why Are Health Disparities Everyone’s Problem? So, if you’ve tried to treat yourself, you might say, “I have taken 1000 milligrams of Tylenol every six hours today without improvement of my pain” or “I iced my pain point for three hours with no improvement.” This way, your physician can make the most accurate treatment call possible, says Dr. Landry.

➋ Ask questions.

➔ Once they share a treatment plan, take notes. “Health professionals tell you a whole bunch of stuff,” says Dr. Cooper. “But once you leave, you’ll think, ‘Wait, what did they say?’” By writing down what your physicians and nurses tell you, you can refer back to your notes, ask questions, and keep an eye out for any irregularities that don’t line up with the healing process they described.

➌ Bring a friend.

➔ Dr. Landry suggests bringing someone along who can speak on your behalf, like a family member or a close friend. “Having someone who is familiar with medicine is most ideal, but even someone at your bedside who can say, ‘I know my mom’ or ‘I know my brother. They’re never in pain like this. This is not usual,’ will help frame the story that this person is off their baseline,” says Landry. Due to COVID-19, most hospitals have set up precautions prohibiting friends and family at patients’ bedsides, so having your physician or nurse speak to your advocate via phone or video call will likely be your only option.

➍ Have your primary care doc back you up.

➔ Another advocate you might consider calling on is your primary care physician (PCP). “Many emergency room patients are sent to the ER by their PCPs, and when that happens it’s nice if the primary care doctor calls the emergency room ahead of time,” says Dr. Landry. So, don’t shy away from asking yours to make a call on your behalf. They’ll take on the work of describing your pain and the treatments they’ve recommended up until this point.

➎ Contact a patient advocacy program.

➔ If neither of these options is available to you, some hospitals have patient advocacy programs, says Onyeka Otugo, MD, MPH, an emergency medicine physician and health policy research and translation fellow at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. You can call the office during or after your appointment to tell a patient representative you’re not getting your pain controlled, you feel like you’re not being heard, and you need someone to act as an intermediary on your behalf. “It’s a very convenient option, but it’s totally dependent on the hospital system, if they have one, and if it’s open while you’re there,” Dr. Landry points out.

➏ Ask for a different doctor or nurse.

➔ A number of things have to fall into place for the options listed above to work. When you’re in pain and likely scared, you’ll have to muster the energy to call on a support system. They, in turn, have to be available. When these things do fall into place, it can make all the difference. But when they don’t, you may end up having to advocate for yourself.

One way to to do this is by requesting a different physician or nurse, Dr. Otugo says, or seeking out a second opinion. You can even ask if there’s a person of color available who can treat you. While this may not be an option—Dr. Landry notes that she’s the only Black woman faculty member in her department, for example—it doesn’t hurt to ask.

What Happens Next

Dismantling the racism ingrained in pain management and the healthcare system would require a considerable overhaul. It would mean pressing pause on the practices and lessons we’ve been told are sure and unshakeable and starting from scratch. Reform isn’t a matter of reverting to a healthcare system that was once “good” and has since become corrupt, says Roberts. How could it be, when the existing infrastructure was never “good” to begin with? The innovations we rely on today on were built on the bodies of Black people only to work against those very same bodies when put into practice.

Upon realizing they weren’t getting the medical care they deserved, someone might have gathered their things and walked out of the hospital. But that risks the consequences of going untreated. It also begs the question: Why should anyone have to take that gamble in the first place?

In Melissa’s case, it was too late. She was mid-colonoscopy, when her pain was dismissed, so leaving wasn’t an option.

Next time, she’ll make sure her provider is aware of racial disparities in pain management. “I just need to confirm that you are aware of the bias in healthcare for Black people and people of color,” Melissa will say. And if they’re not, she’ll find someone else to treat her.

3 Patient Advocacy Programs You Need to Know About

Independent patient-advocacy programs: