summary

The “Spiritual Geographies” exhibition at UCI’s Jack and Shanaz Langson Institute and the California Institute of Art features artists such as Sierra Club co-founder John Muir, Protestant ministers, theosophists, and various painters. explore how they used landscape painting to convey their theological ideas.

Many people see God in nature.But what then? painting natural? That’s the subject of “Spiritual Geography: Religion and Landscape Art in California, 1890-1930,” a new exhibition at UCI’s Jack and Shanaz Langson Institute and the California Institute of Art.

The show, on display from March 2 to June 8, explores how Sierra Club co-founder John Muir, Protestant pastors, theosophists, and various painters used landscape photography to convey their theological ideas. Find out how you used it.

Although the works do not contain overt sacred symbols, religion “definitely influenced a lot of landscape paintings” around the turn of the last century, curator Michaela Mormann said. She developed this exhibition after noticing a “spiritual undercurrent” in some of Langson IMCA’s collections.

Examining how religion has influenced art is almost taboo in museum circles these days, Morman says. But that started to change a few years ago, she points out.

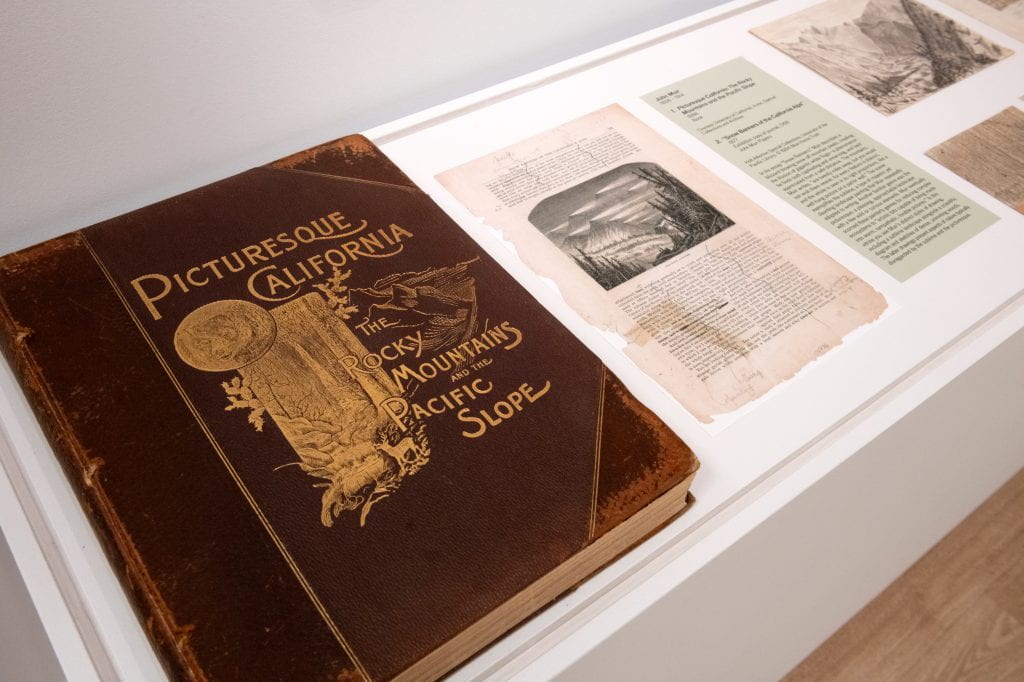

The first section of Langson IMCA’s show revolves around Muir, who memorized the Bible at age 11 and came up with mystical metaphors to lobby for conservation in California. According to Morman, he called the artist whose most famous work was Yosemite Valley God, compared immersion in nature to baptism, and wrote about the “sacrament” of sipping “sequoia blood.”

From Muir, the gallery became Protestant, and in 1919th Sermons and tracts of the century evoked panoramic landscapes as conduits to the divine. Morman said some pastors asked their congregations to imagine the Bible story taking place in rural California rather than Israel.

German-born artist William Wendt, a devout Lutheran who married a Catholic sculptor, was also known as the dean of Southern California’s landscape painters and titled several of his works after Bible verses. Ta. However, the other names remained a mystery. Morman discovered that one of his most puzzling songs, “Tender Evening Bendes”, was inspired by a now unknown 1800s hymn of his. For viewers at the time, she says, the effect was similar to watching a music video today. Once you know the title, you’ll hear the song in your head while looking at the art. Visitors to the Langson IMCA can listen to the song on headphones and read the lyrics to the 1894 hymn on display nearby.

Unraveling the story behind “Bendes” led Mollman to make connections between other Wendt paintings and forgotten Christian hymns, and she wanted to publish a magazine article about her discoveries. I am.

The third wing of “Spiritual Geography” features artists influenced by Theosophy. Theosophy is a fusion of Buddhism, science, and occultism developed by Helena Blavatsky, a Russian immigrant who was based in Point His Roma and claimed paranormal powers.

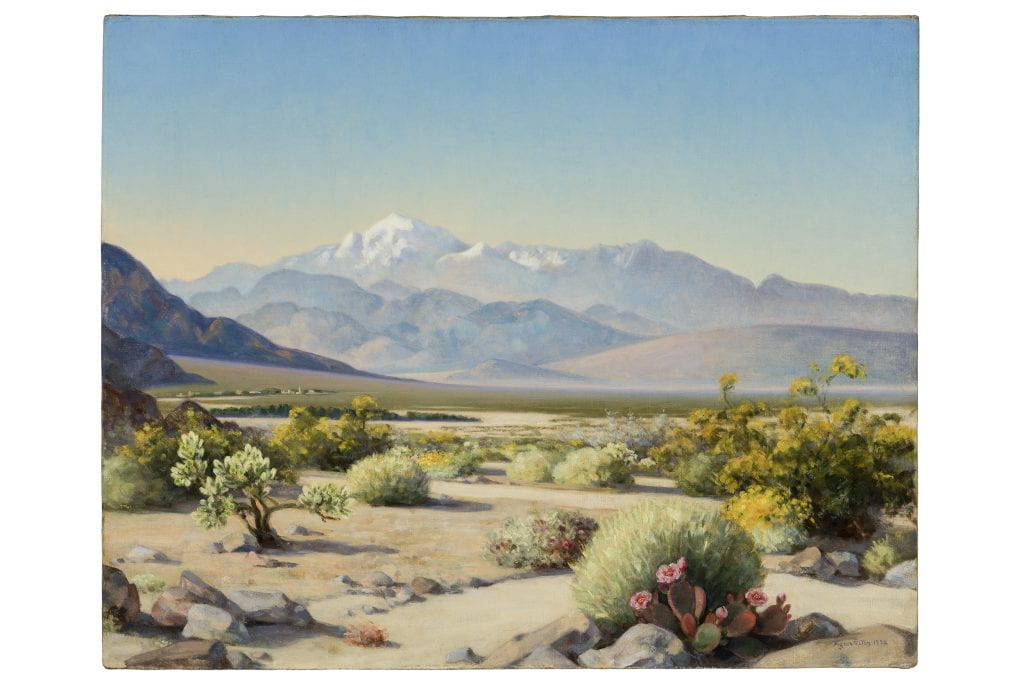

Agnes Pelton’s “San Gorgonio in Spring” depicts mountains that Theosophists believed were spiritual guardians and portals to other dimensions. Artist Maurice Brown conveyed the sect’s doctrine of reincarnation by depicting plane trees in different seasons, from the withering heat of summer to the lushness of spring leaves, subtly depicting the cycle of death and rebirth. Morman says.

The final stop on Langson IMCA’s Spiritual Art Expedition focuses on California’s Spanish mission network, but not because the artists are Catholic or trying to pass on the Church’s teachings.Rather, the 1884 novel Ramona It sparked a wave of public interest in relics of the state’s religious past.

Many of the plein air paintings were romantic depictions of the mission, but there were also darker interpretations, Morman said. Some saw the depictions of crumbling buildings and ruins as evidence of the decline of Catholicism and the rise of Protestantism.

Overall, the exhibition highlights 35 Impressionist and early modernist paintings, as well as rare books, sketches, diaries, newspaper clippings, and other archival materials.

“This show is a love letter to my new hometown of California,” says Morman, who was born in Texas and grew up in South America, Kentucky and France. “We hope our visitors leave with an understanding of our state’s complex history as a ‘spiritual frontier,’ shaped not only by conflict and persecution but also by ideals of religious tolerance.”

Full artwork credits:

john muir Picturesque California: Rocky Mountains and Pacific Slope, 1888 (1894 edition). Book. Provided by University of California, Irvine.Special collections and archives

John Muir “Snowy Flag of the California Alps” Harper’s new monthly magazine, Section 55, no. 326, 1877. Copy of the exhibition. 068 John Muir Papers, Holt Atherton Special Collections, University of the Pacific Library. © 1984 Muir Hanna Trust

William Wendt Gentle Evening Bendes, 1938, oil on canvas, 46 x 40 inches. Provided by: Hoefer Family Foundation

Agnes Pelton Spring San Gorgonio, 1932, oil on canvas, 24 x 30 inches. Back Collection of the UCI Jack and Shanaz Langson Institute and the Museum of California Art

George K. Brandliff Old San Juan Bell1929-1933, oil on canvas, 19 x 23 inches, gift of UCI Jack and Shanaz Langson Institute and California Institute of Art, Irvine Museum of Art

william adam San Juan Capistrano Mission back corridorafter 1894, oil on canvas, 16 x 21 inches, gift of UCI Jack and Shanaz Langson Institute and California Institute of Art, Irvine Museum of Art

George Gardner Simmons The Arches1906-1915, oil on canvas, 10 x 14 inches, gift of UCI Jack and Shanaz Langson Institute and California Institute of Art, Irvine Museum of Art