Longevity has the world on fire these days, with everyone competing for the perfect amount of mucus to smear on their faces as they take the wild swim toward eternal life. But can we learn the secrets of longevity from nature? And if so, what does the world’s longest-living vertebrate have to say about it?

New experimental research on the subject suggests that metabolic activity may be key to the Greenland shark’s incredible longevity. This improved understanding may help protect these animals on a warming planet, as well as inform interventions for human cardiovascular health.

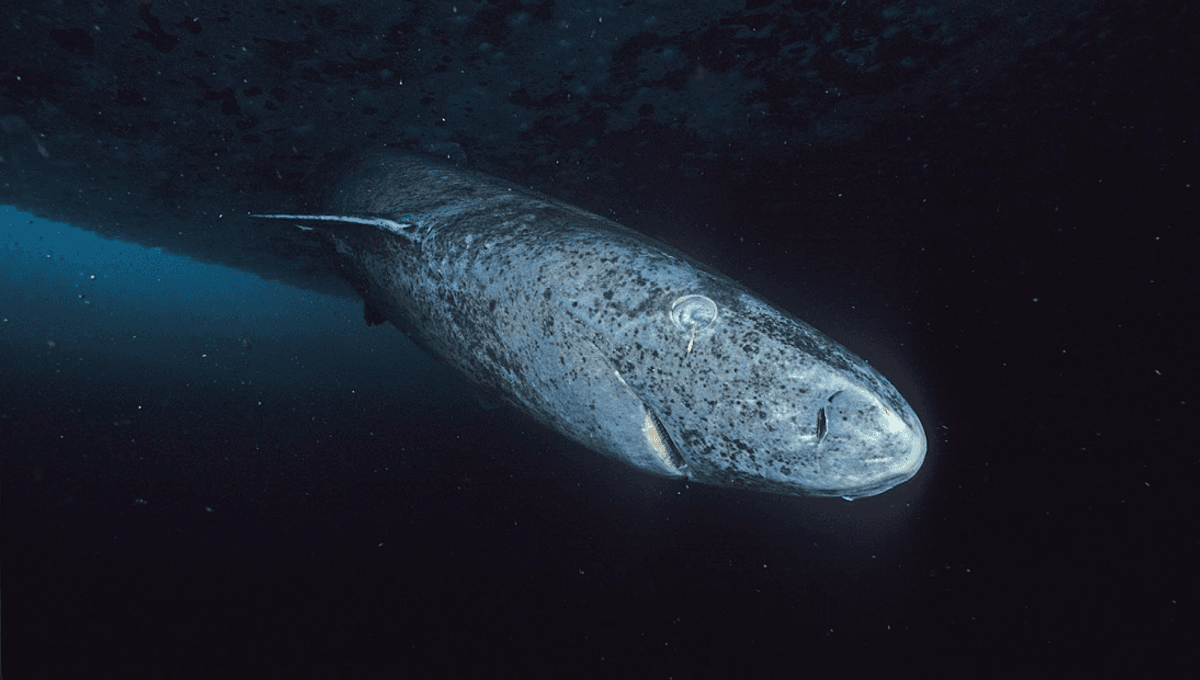

Greenland Shark – Scientifically Somniosus microcephalus Their lifespan is expected to be at least 270 years, but in the most amazing cases they can live for over 500 years (weirdly, we know this thanks to nuclear weapons). It has long been suggested that the cold environment they live in, and the little effort it takes to move around, may be key, but a team including Euan Camplison, a doctoral student at the University of Manchester, UK, decided to look more closely.

To explore the adaptations that enable Greenland sharks to live so long, the team carried out enzyme analyses on preserved muscle tissue samples. Such samples provide a unique opportunity to study these animals, which are the focus of the University of Copenhagen’s “Old and Cold” project.

A tissue collection of Greenland sharks.

Image credit: Ewan Camplisson

“During the expedition, the main focus will be to capture sharks and equip them with both electronic and physical tags so that we can release them and either monitor where they swim (via the electronic tag) or record their growth if they are recaptured and identify them via the physical tag,” Camplison explained to IFLScience.

“Sometimes sharks are injured during this process and may not survive release. To avoid the shark suffering unnecessarily, we sometimes make the decision to ethically euthanize the shark rather than release it back into the ocean. In these cases, we collect samples for future research so the animal is not wasted and can be used for scientific research. The remains of the shark are donated to local fishermen and hunters, who feed shark meat to their sled dogs to ensure the animal is not wasted.”

The team measured the metabolic activity of shark enzymes using a spectrophotometer in preserved red muscle samples and observed the sharks at different ages and environmental temperatures. Surprisingly, they found no significant changes in the metabolic activity of the sharks’ muscles. This indicates that their metabolism does not decline with age as in other animals, which may be a major contributing factor to the longevity of sharks.

“For us, this is important because most animals that show typical signs of aging experience a decline in some enzyme activity and an increase in others as they get older,” Camplison says. “This is all part of a natural metabolism, which slows down and changes over time as we age. The fact that we don’t see this in the Greenland sharks suggests that they don’t show this typical sign of aging.”

The results showed a change with environmental temperature, with metabolic enzymes showing a significant increase in activity in hotter areas, suggesting that muscle metabolism is not adapted to the polar environment, Camplison said, otherwise the difference in activity with temperature would be smaller.

The team hopes that a better understanding of Greenland sharks will help them understand how they respond to Earth’s rapidly changing climate, and may also provide insights that can be applied to the study of human cardiovascular health as we age.

“I have other projects studying ageing in Greenland sharks,” Camplison says, “looking at metabolic changes is just one of these projects, but in this small project we will also be looking at different tissues from the Greenland shark that may show different metabolic profiles, as well as enzymes that will give us even more insight into the metabolism of this incredible species.”

The research will be presented at the Society for Experimental Biology Annual Meeting, which will take place July 2-5, 2024 in Prague.