“Over the past 10 to 15 years, the proportion of people needing mental health support has increased,” says Smith, whose focus is on treating young people.

The reasons are complex and wide-ranging, she says, but include the long-term economic impact of the financial crisis, which puts strain on families, and the devastating effects of the pandemic and lockdown, which increase loneliness and isolation.

She also cited expensive and unsafe housing and the potential for social media to repeatedly expose users to negative posts as factors.

Treating so many people is difficult, and there aren’t enough doctors to meet their needs. Mr Smith, who is also president of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, said almost a fifth of consultant posts were vacant in the specialist field.

NHS figures tell a similar story. Last year, 1.2 million people were placed on waiting lists for community mental health services.

More than 250,000 children and young people who received mental health services between 2022 and 2023 were still waiting for help at the end of that period, a study by Children’s Commissioner for England has found.

This is not just a crisis for individual patients or the health service as a whole. Poor mental health is now highly prevalent and a drag on the economy.

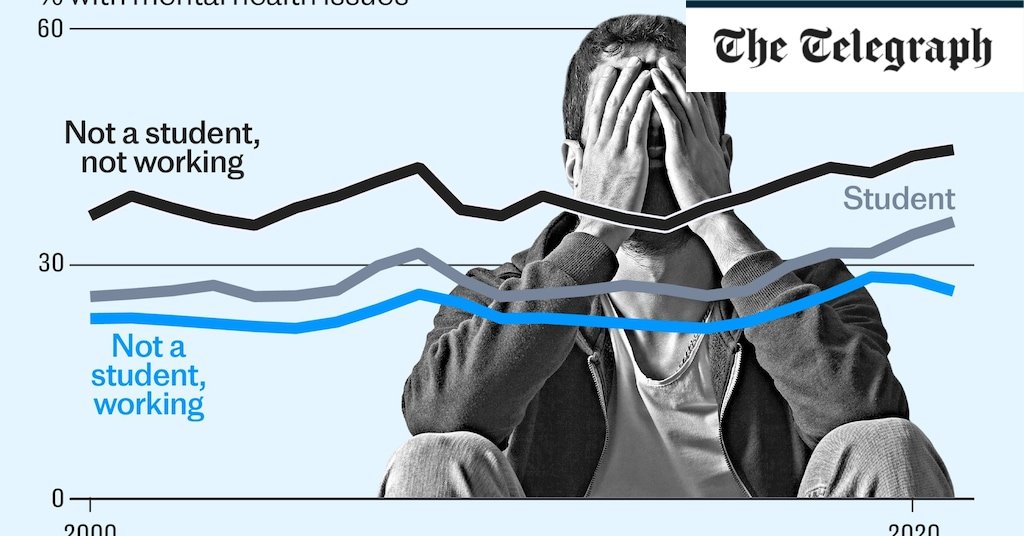

“The number of young people unable to work because of poor health has doubled in the past decade. People in their early 20s are now more likely to be unemployed due to poor health than those in their early 40s. This is really surprising,” says Louise Murphy, an economist at the Resolution Foundation.

“It’s very different from what we saw 25 years ago. Back then, there was a very simple trend that the older you got, the more likely you were to be in poor health, and therefore the more likely you were to be unemployed. .”

Poor mental health is a major driver of this trend.

Missing the early stages of your career can have lifelong effects on your earning power, known among economists as “scars.” In fact, people never catch up after missing these important early opportunities.

Policymakers are concerned and looking for solutions. But at the moment it seems likely that the situation will get even worse.

The number of school children suffering from mental health conditions is increasing. This means that unless something changes dramatically, a new generation of young people is likely to struggle when finishing school and looking for work if they are healthy enough.

More than one in five pupils aged eight to 16 are thought to have a ‘suspected mental health disorder’, according to NHS research. This is up from 1 in 8 people before the pandemic.

On top of that, an additional 12% are considered “probably diseased.”

Among teenagers aged 17 to 19, this number rises to nearly a quarter. In this group, it is thought that almost one in three young women may suffer from the disorder.

According to Smith, half of all mental illnesses begin before the age of 14, and 75% by the age of 24. With early treatment, about a quarter of cases are completely cured. If you wait, you run the risk of the patient developing a chronic disease and relapse.

Tackling this mental health crisis and the resulting unemployment problem is a priority for the government.

Employers are facing severe staff shortages, with more than 900,000 vacancies at the start of the year, according to the Office for National Statistics. Going the extra mile to hire and retain people with mental health issues would be good for both workers and companies.