Alive and Alive: Caring for the Soul in Turbulent Times; Elizabeth Oldfield

(London: Hodder & Stoughton, £18.99/€26.99)

Elizabeth Oldfield was director of Theos, a London-based think tank, from 2011 to 2022. Founded in 2006 with the support of Cardinal Murphy O’Connor, the then Archbishop of Westminster, and Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams, Theos researches issues of public concern from a Christian perspective and gives a voice to the Christian tradition in the public sphere.

A distinction can be made between debate and dialogue: debate is entering into an argument in order to correct errors and reveal truths, dialogue is bringing what you see from your perspective into the perspective of the “other”. The common ground found in this merging of perspectives leads to a shared understanding, even if agreement is not reached. Theos’ style is dialogical, and Oldfield’s book is a great example of that style.

principle

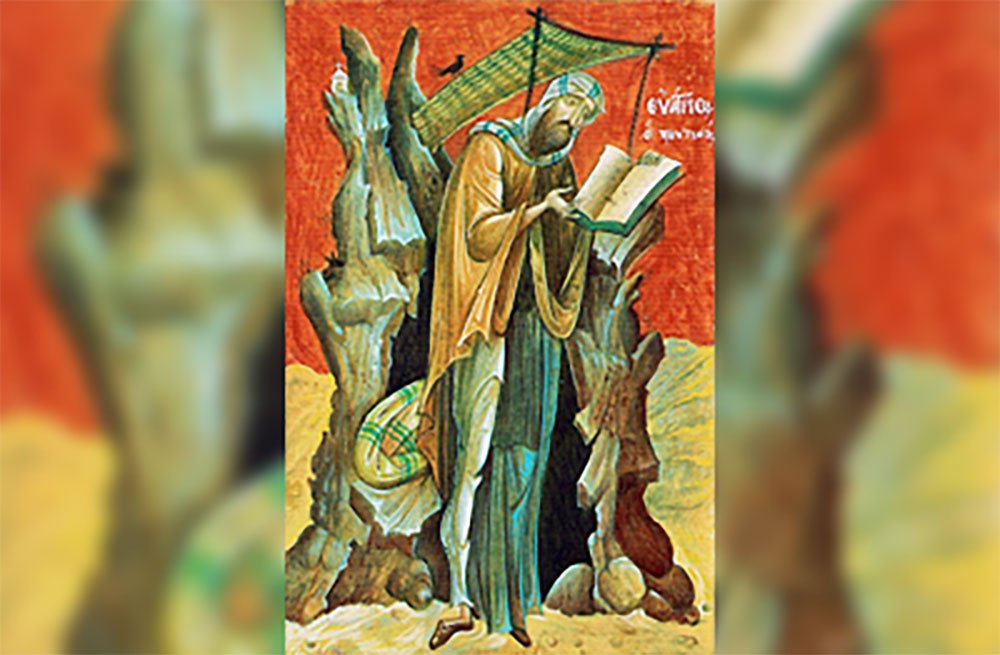

The book, she says, is “written for those seeking spiritual strength who want to know what Christian practice, attitudes, and principles can teach us.” She does this by examining the deadly sins listed by Evagrius Ponticus (345-399 AD), which may seem an unusual choice, given that sin receives little or no attention in secular discourse, where a focus on “self-esteem” precludes attention to “serious shortcomings.”

Catholics still say prayers, but I can’t remember the last time I heard a sermon on sin. I suspect I may be part of the last generation that can even enumerate the sins of anger, greed, sloth, jealousy, gluttony, lust, pride, etc.

We learned in grade school that sin offends God and deserves punishment, but can be forgiven. This is not a good starting point for developing understanding as an adult.

Oldfield grounds her account in her own experience and in the ways we screw things up, frustrate our desires, and damage our relationships. She weaves together considerable intelligence, psychological insight, sociological sensibility, and the wisdom of tradition to lead the reader into a world in which the particular damage each sin does to our flourishing is clearly visible, where our weaknesses are laid out before our eyes, and our responsibility for why things go wrong is made clear.

We create our own hell by distorting our relationships with others and the world around us.

Sartre’s assertion that “hell is other people” is an extreme example of a common fear that human relationships threaten our independence, limit our freedom, and expose us to exploitation.

Whereas Sartre and our culture put the individual first, Oldfield puts relationships first. She correctly surmises that the individual emerges from relationships in which the capacity for autonomous action is formed. We create our own “hell” by distorting our relationships with others and the world around us. And the deadly sins express these.

value

I believe she succeeds in convincing nonbelievers that there is much value in the Christian explanation of sin, and believers, too, will learn a lot from a compelling retelling of a part of tradition that has remained in the shadows. But questions remain.

The notorious atheist Richard Dawkins recently declared himself a “cultural Christian.” He believes that talk of God and revelation is nonsense, but he thinks that the norms Christianity promotes and the insights it offers are worth preserving. Has Oldfield done more than contribute to “cultural Christianity”?

Where is God on her account? Proving God’s existence is a key challenge for those who challenge the atheistic, scientific foundations of our secular culture.

effort

Believers benefit from this effort. Their faith is strengthened and they are protected from the temptation to imagine God as some kind of superhero, the biggest and most powerful being in the universe. A Creator is not a living thing. But it is doubtful that these arguments have convinced unbelievers to believe.

If mortal sin describes the hell we create for ourselves, it also illustrates the happiness that can be found in human flourishing.”

So Oldfield wisely leaves such considerations out of the conversation: she wants to show what it means to “believe in God” by telling us what it meant to her: a relationship based on the experience of deep love, which transforms what might have been a hopeless portrayal of human misery.

To recognize the damage that sin causes is to simultaneously recognize the good it prevents. If mortal sin represents the hell we create for ourselves, it also represents the happiness that can be found in human flourishing.

Alfield’s story of faith lost and found, of the rewards and challenges of family, work, and community, is also the story of how God’s love is transformative: When we respond to that love by striving to love our neighbor, we see and come closer to realizing the good our nature is capable of.

Non-believers seeking “spiritual strength” will be inspired by their need for salvation and that it is at hand. Believers will find a new understanding of the Atonement and encouragement for renewed effort.

Oldfield’s easy-going, relaxed style is easy to read, yet rooted in deep theological understanding and a firm philosophical grasp.