1 Introduction

Premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) is a syndrome characterized by ovarian hypofunction occurring prior to the age of 40, with an approximate incidence of 1% (1). Various factors including genetic (2, 3), immunological, viral, iatrogenic (4, 5), and environmental factors are common contributors to POI, with over 50% of patients encountering an etiology that remains undetermined (6). Irregular menstruation is a common manifestation in POI patients, presenting as oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea persisting for ≥4 months. The condition is characterized by elevated levels of gonadotropins and reduced estradiol, ultimately leading to a decrease in reproductive capacity. Symptoms of POI encompass hot flashes, perspiration, reduced libido, bone rarefaction, metabolic disturbances, and other repercussions. It not only impacts fertility, mental health, and quality of life but also exerts influence on various systems, including skeletal, cardiovascular, urogenital, and nervous systems among others (6–8). The concept of POI was introduced in 2008 (9), but its diagnosis has always lacked a precise criterion. In 2016, the European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) lowered the cutoff point for follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) in early-onset ovarian insufficiency to 25 IU/L. This adjustment has drawn attention to POI, differentiating it from premature ovarian failure (POF).

Common treatments for POI encompass hormone replacement therapy (HRT), selenium and vitamin E supplementation, exercise therapy, and more (7). HRT is sequential estrogen–progesterone therapy with progesterone supplementation for 10 to 14 days per month in addition to continuous estrogen use. HRT stands as the recommended standard protocol for individuals with POI to alleviate symptoms of low estrogen (10, 11). Additionally, HRT has the potential to prevent cardiovascular diseases and bone rarefaction. However, this therapy has limitations as it cannot enhance ovarian activity, and breast cancer is a contraindication (12). Oral hormone therapy may elevate the risk of hypertension in women (13). Furthermore, judicious assessment is imperative for the use of HRT in POI patients with conditions such as SLE, gallbladder disorders, epilepsy, or asthma (6, 14, 15). A novel therapy known as in-vitro activation of follicles has been introduced, with a limited number of clinical pregnancy reports; however, its efficiency falls below the optimal level (16–18). Advanced treatments, including immunotherapy, stem cells, and gene editing, are currently in the research stage (19, 20).

Acupuncture, regarded as a traditional Chinese non-pharmacological intervention, has demonstrated promising outcomes, a high degree of safety, and minimal adverse effects. It is widely utilized in the field of reproductive endocrinology (21, 22). Recently, there has been a surge in randomized controlled trials investigating the efficacy of acupuncture for POI. It is imperative to integrate and systematically evaluate these research findings. Given the revised diagnostic criteria for POI by ESHRE in 2016 and the limited attention to the impact of acupuncture on the subset of POI patients with FSH >25 IU/L, a meta-analysis and systematic evaluation of existing data were conducted to furnish a pertinent reference for clinical practice.

2 Materials and methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (23) were followed in the reporting of this systematic review and meta-analysis (PROSPERO registration No. CRD42023467751).

2.1 Search strategy and study selection

Eight databases were comprehensively searched, namely, the English-language databases Cochrane Library, Web of Science, EMBASE, and PubMed and the Chinese-language databases Wanfang, VIP Information, CBM, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) from inception up to October 2023. Our retrieval strategy comprised three main components: clinical conditions (including premature ovarian failure, primary ovarian failure, primary ovarian insufficiency, premature ovarian insufficiency, premature menopause, POI, POF), interventions (such as acupuncture, electroacupuncture, manual acupuncture, warming needle, acupuncture therapy, needling, needles, needle therapy), and study types (RCT). No retrieval filters or limits were applied. To identify redundant papers, researchers manually examined the reference summaries of the retrieved articles. The initial screening of articles, independently conducted by the first two authors (H.J.C. and H.Z.L.), involved a thorough review of titles, abstracts, or full text to substantiate the eligibility of the studies. Any uncertainties regarding inclusion were deliberated among the other authors (L.W.X and S.M.L).

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies that met the following criteria were included: 1) subjects: the standard of diagnosis was based on the clinical recommendations for the treatment of POI patients presented by ESHRE in 2016: a) women under 40 years old with amenorrhea/oligomenorrhea or symptoms of estrogen deficiency, b) oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea persisting for ≥4 months, and c) FSH level >25 IU/L on two occasions with a gap of >4 weeks; 2) intervention: acupuncture (including manual acupuncture and electroacupuncture regardless of the level of needling techniques), as well as the singular or combined use of Chinese herbal medicine or (and) HRT. Studies would be included if acupuncture was regarded as an adjuvant therapy for POI, and there were similar concomitant treatments between the experimental group and the control group; 3) controlled method: HRT, Chinese herbal medicine, or a combination of HRT and Chinese herbal medicine; 4) outcome indicators with sufficient data: effective rate, FSH, LH, E2, AMH, etc. Blood tests were performed before and after treatment, respectively, on the second to fourth days of the menstrual cycle to evaluate the basic hormone levels during the cycle; 5) study type: RCT; and 6) availability of complete data in the literature and precise data in the experimental and control groups.

Studies that met the following criteria were excluded: 1) interventions without acupuncture treatment (e.g., massage, moxibustion, or electrostimulation without needle); 2) interventions of control groups receiving different acupuncture treatments (e.g., acupoint catgut embedding); 3) patients suffering from other endocrine diseases (e.g., polycystic ovary syndrome, thyroid dysfunction, and hyperprolactinemia); 4) lack of definite or self-made criteria for efficacy evaluation; 5) studies about animal experiments, commentaries, editorials, experience introductions, conference articles, reviews, graduation theses, and case reports; 6) duplicate publication; 7) literature with incomplete outcome index data or full texts that cannot be obtained; and 8) literature with incorrect data and unidentified authors.

2.3 Data extraction and quality evaluation

Two authors, H.J.C. and H.Z.L., independently extracted relevant data using a standardized form. Information regarding the characteristics of the study population (such as sample size, age, and disease duration), treatment specifics (including types of interventions, acupoints, and duration), and group-wise results was collected.

Meanwhile, the quality assessment of the included studies was carried out by two independent reviewers (H.J.C. and H.Z.L.) utilizing the Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias tool. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion with L.W.X.

The STRICTA (Standards for Reporting Interventions in Controlled Trials of Acupuncture: the STRICTA recommendations) (24) standard was used to evaluate acupuncture intervention measures. A response is considered “positive” by the STRICTA standard if every item is fully recorded. There were three categories for the reporting rate (N = reported RCTs/13): high (N ≥ 80%), moderate (N = 50%–80%), and low (N < 50%).

2.4 Statistical analysis

The data management software RevMan 5.3 was employed for data organization. Each group’s mean and standard deviation of the pretreatment and posttreatment results was collected. Continuous data were measured using the mean difference (MD) or standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The following formula was used to figure out the D-value of the statistical mean and standard deviation: S * S = S1 * S1 + S2 * S2 − 2 * R * S1 * S2; D = M1 − M2 (D-value, difference before and after treatment; S, standard deviation of D-value; S1 and S2, standard deviation before and after treatment, respectively; M1 and M2, mean value before and after treatment; R = 0.4) (25). Statistical significance was established at p <0.05 on both sides. Dichotomous variables, such as the total effective rate, were presented as the risk ratio (RR). Additionally, I2 statistics were utilized to assess interstudy heterogeneity. In cases of non-significant heterogeneity, we adopted the fixed-effects model; otherwise, the random-effects model was employed. A subgroup analysis based on the type of intervention was conducted to explore potential sources of heterogeneity. If a meta-analysis was considered inappropriate, we would offer a qualitative description of the results. To ensure result stability, a sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding specific studies. Moreover, if at least 10 studies were included, Begg’s tests and funnel plots were adopted by evaluating the p-value for publication bias.

3 Results

3.1 Included articles

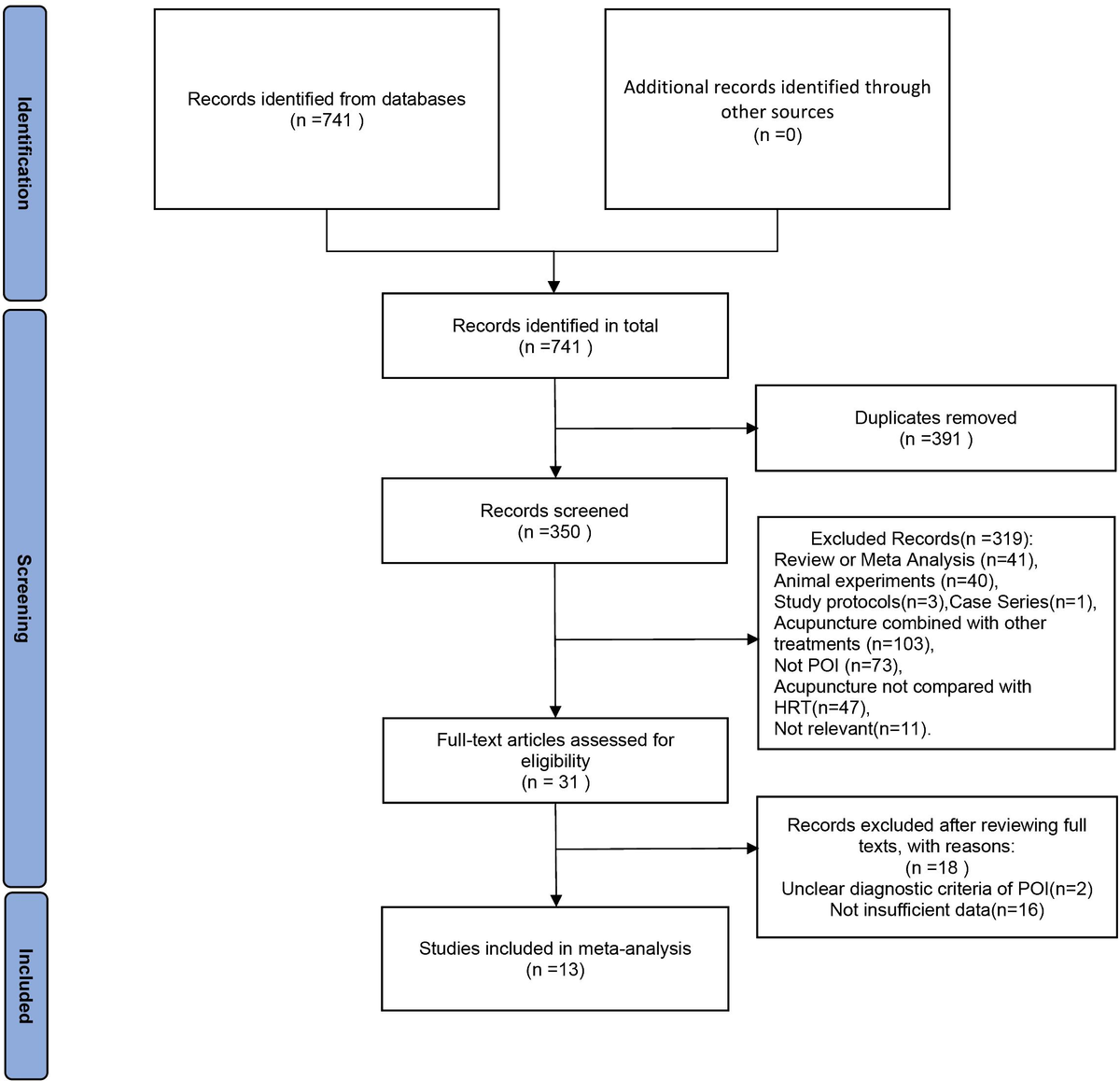

Figure 1 illustrates the flowchart utilized for selecting publications. Initial database searches yielded 741 papers related to the therapeutic efficacy of acupuncture therapy in the treatment of premature ovarian insufficiency. After removing 391 duplicate publications, 350 pieces of literature remained. Upon reviewing the titles and abstracts among the remaining studies, 319 papers were excluded for failing to meet the inclusion criteria. Subsequently, 18 additional studies were excluded due to non-compliance with POI diagnostic criteria or insufficient data for evaluation. Finally, the meta-analysis included 13 RCTs published between 2019 and 2023.

Figure 1 The PRISMA flowchart.

3.2 Study characteristics

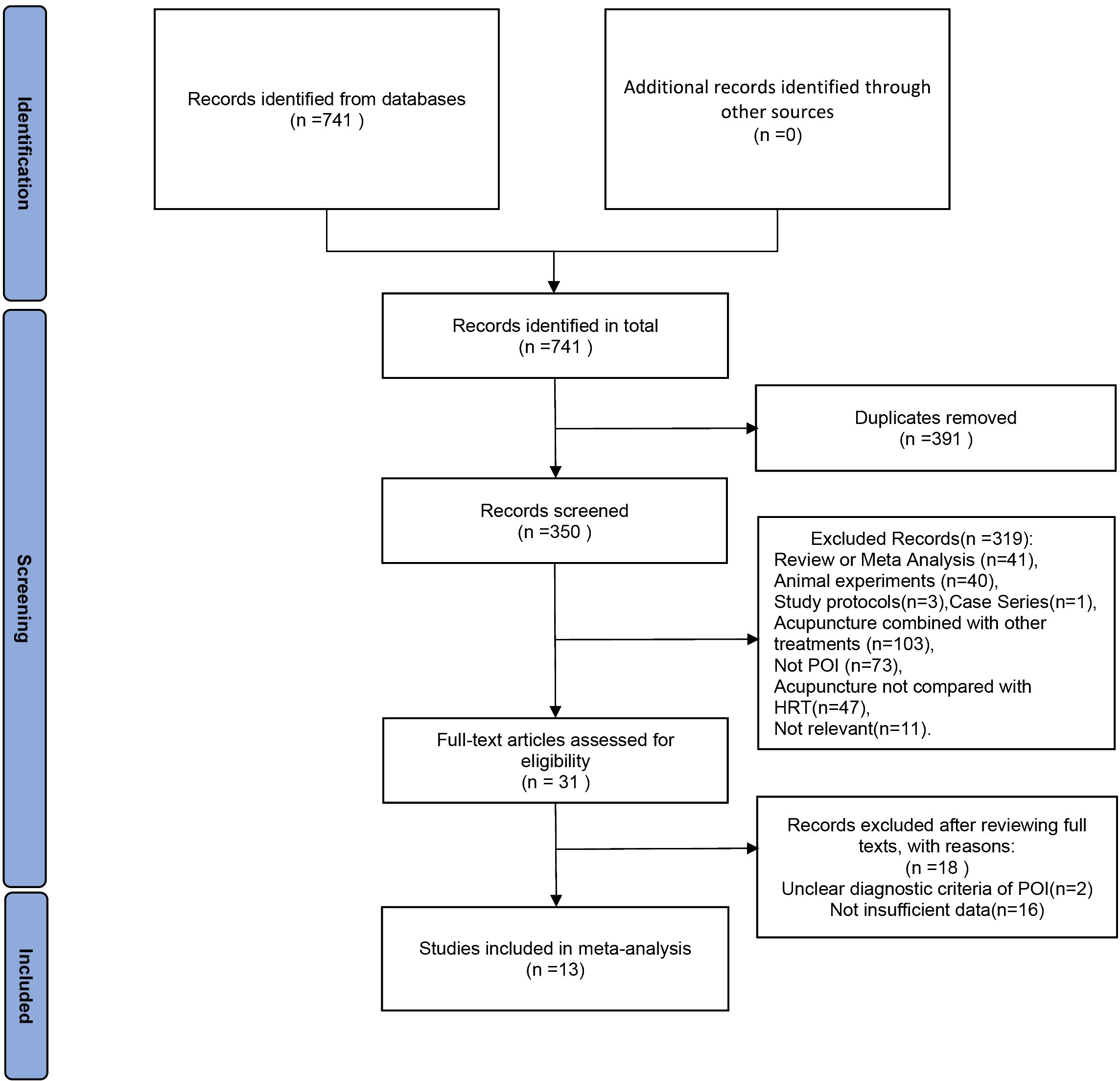

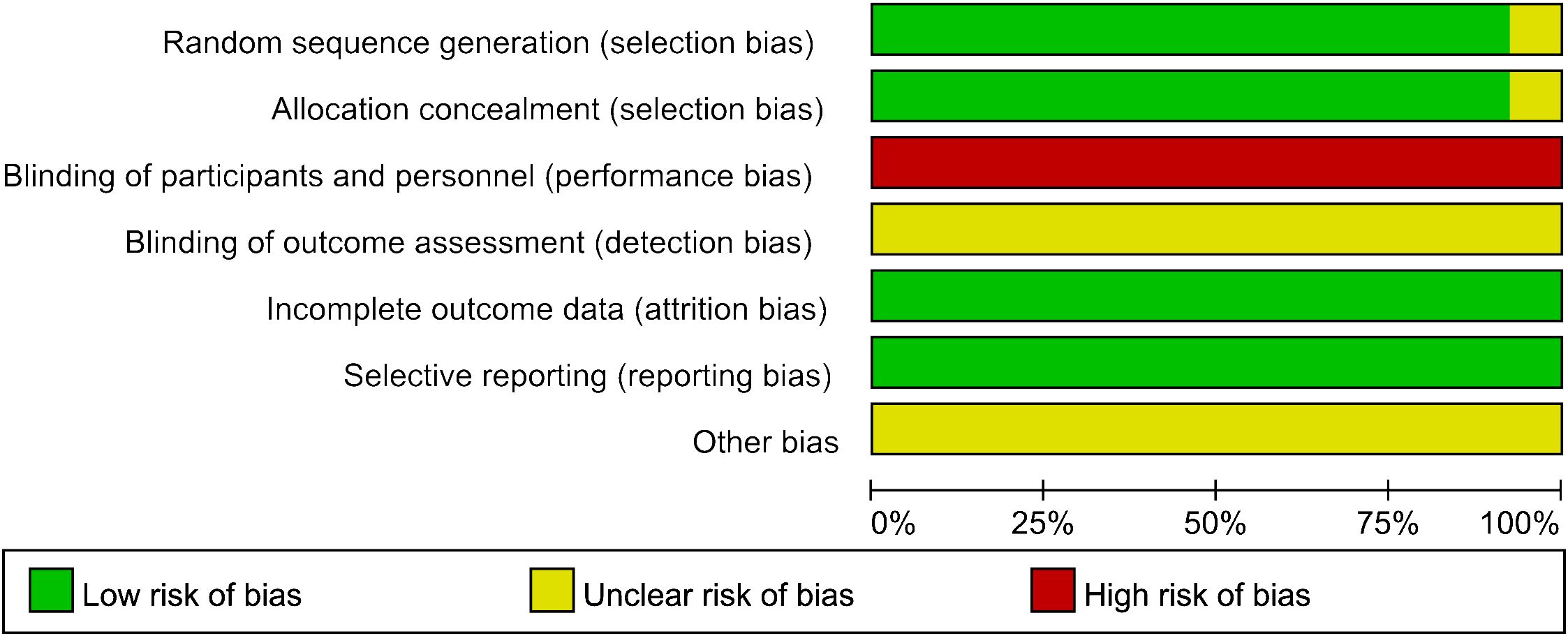

We incorporated 13 RCTs, all conducted in China and published in Chinese between 2019 and 2023. The studies encompassed 775 POI patients, divided into an experimental group (acupuncture group) and a control group, with 388 and 387 cases, respectively. In the studies, blood samples were collected on days 2–4 of the menstrual cycle to assess baseline sex hormone indices. Twelve of the studies collected blood samples before and after the last treatment, while the other study (26) collected blood samples before treatment and 3 months after the cessation of treatment, respectively. Among them, 13 reported FSH levels (26–38), 12 reported LH and E2 levels (26–33, 35–38), 8 reported AMH levels (26, 27, 31–33, 35–37), 5 trials reported the total effective rate (26, 30–32, 35), and 9 presented adverse events (26, 27, 29–33, 35, 38). Baseline homogeneity was observed across all RCTs. Comprehensive details on the characteristics of the study are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Study characteristics.

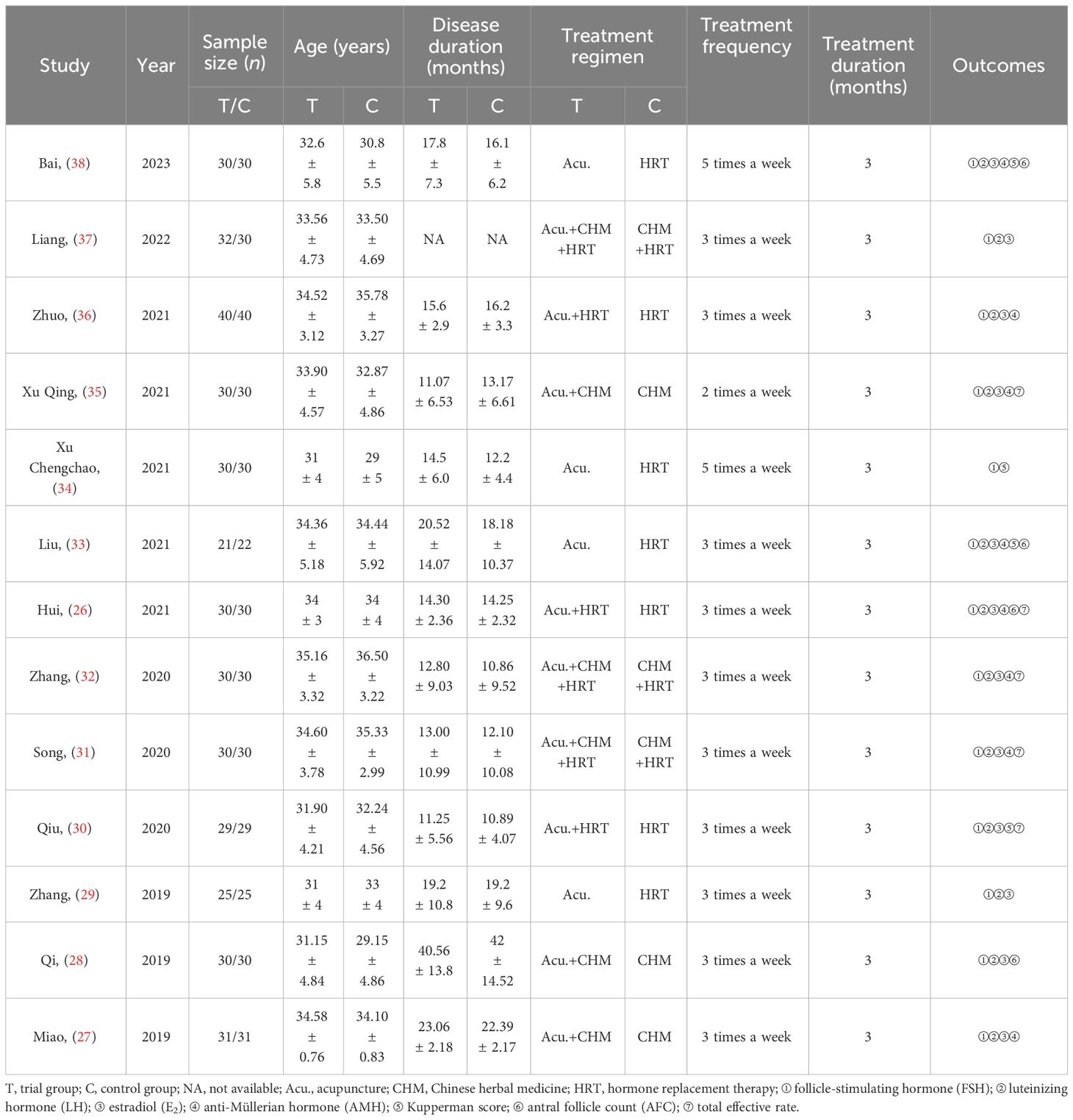

3.3 Quality assessment

Except for Song (31), the methodological quality of all studies regarding selection bias was assessed as low risk due to clear procedures and concealed allocation in the patient randomization process. Given the inherent limitation that acupuncture therapy cannot be blinded, all included RCTs were categorized as “high risk” for participant and staff blinding. Incomplete outcome data and selective reporting were considered to pose a low risk of bias across all studies. Among the 13 studies, no indication of potential bias was identified (Figure 2). The quality of interventions reported was evaluated against the STRICTA list, with a mean reporting rate of 71.04% for all entries (Table 2). In summary, the quality of the included studies was considered moderate.

Figure 2 Risk of bias assessment.

Table 2 Quality evaluation based on the STRICTA list.

3.4 Outcome measurements

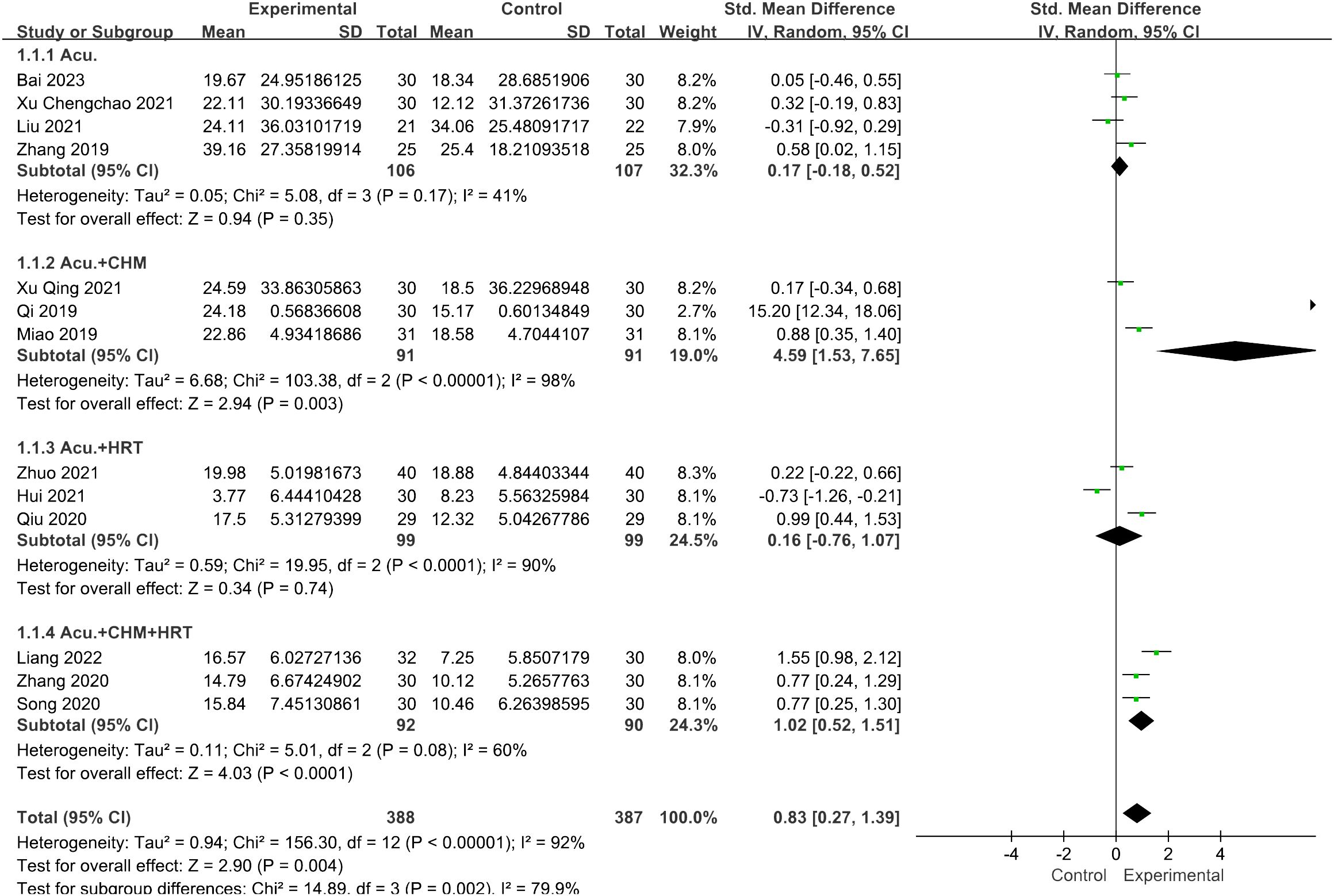

3.4.1 FSH levels

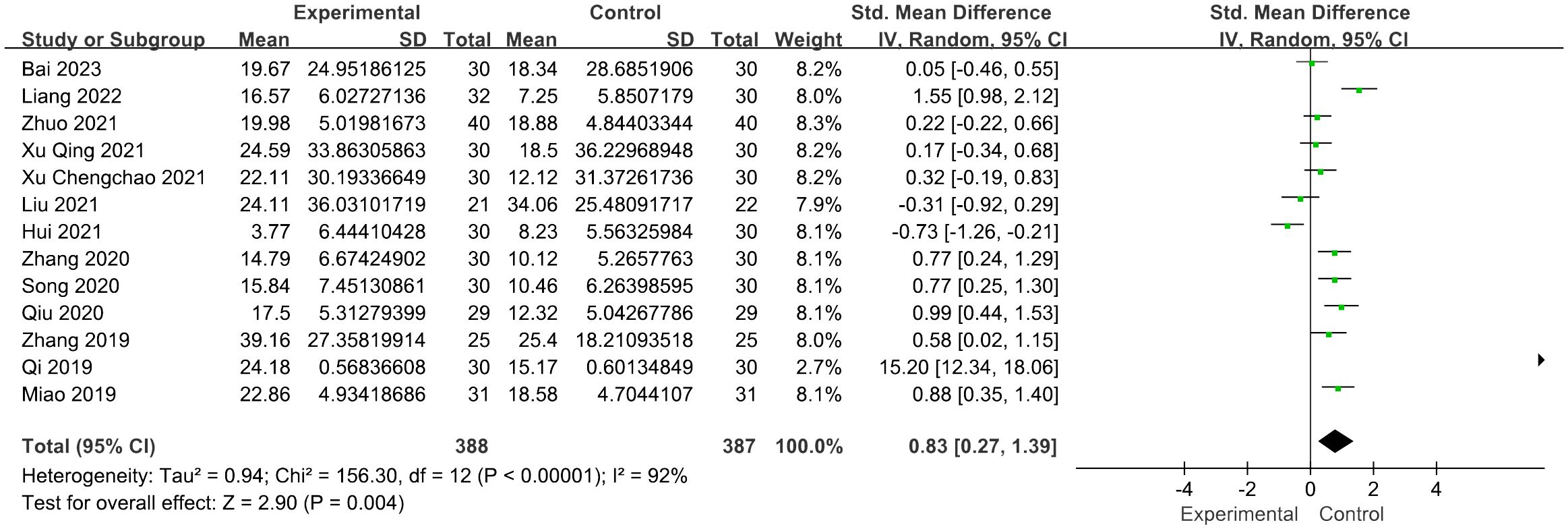

Thirteen studies reported FSH levels of 388 participants in the acupuncture group. Combining the results of these studies showed that acupuncture dramatically reduced the levels of FSH in women with POI [SMD = 0.83, 95% CI (0.27, 1.39), I2 = 92%, p = 0.004] (Figure 3). Sensitivity analysis was employed to confirm the robustness of the aggregated outcomes.

Figure 3 Forest plot illustrating the relationship between FSH levels and acupuncture therapy.

3.4.2 LH levels

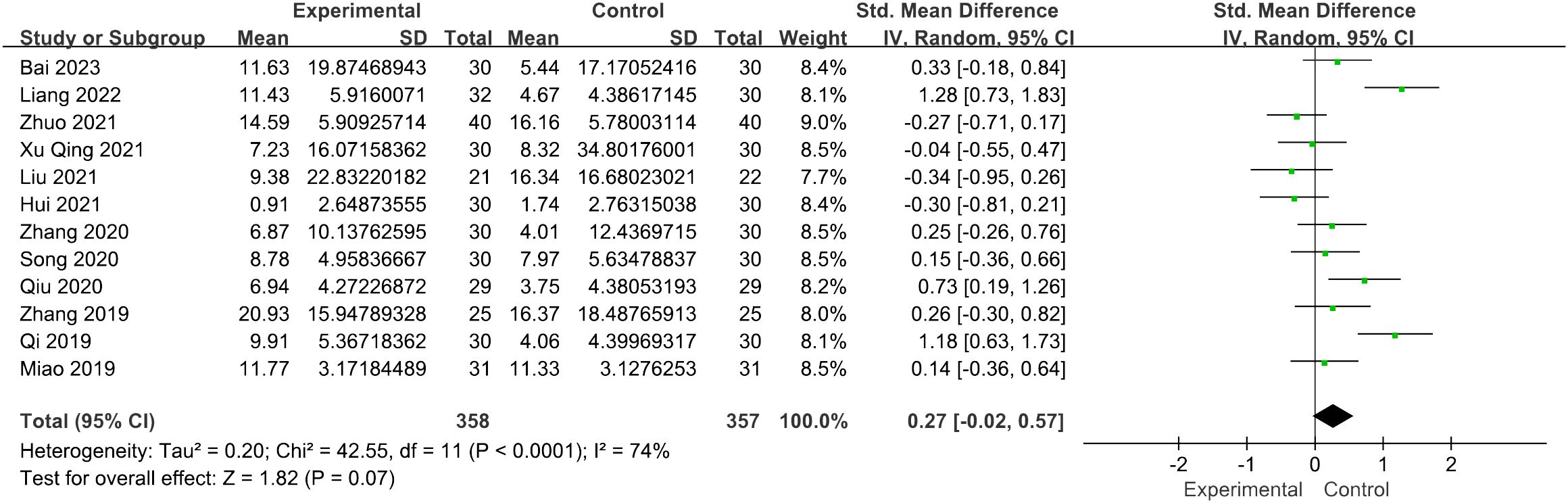

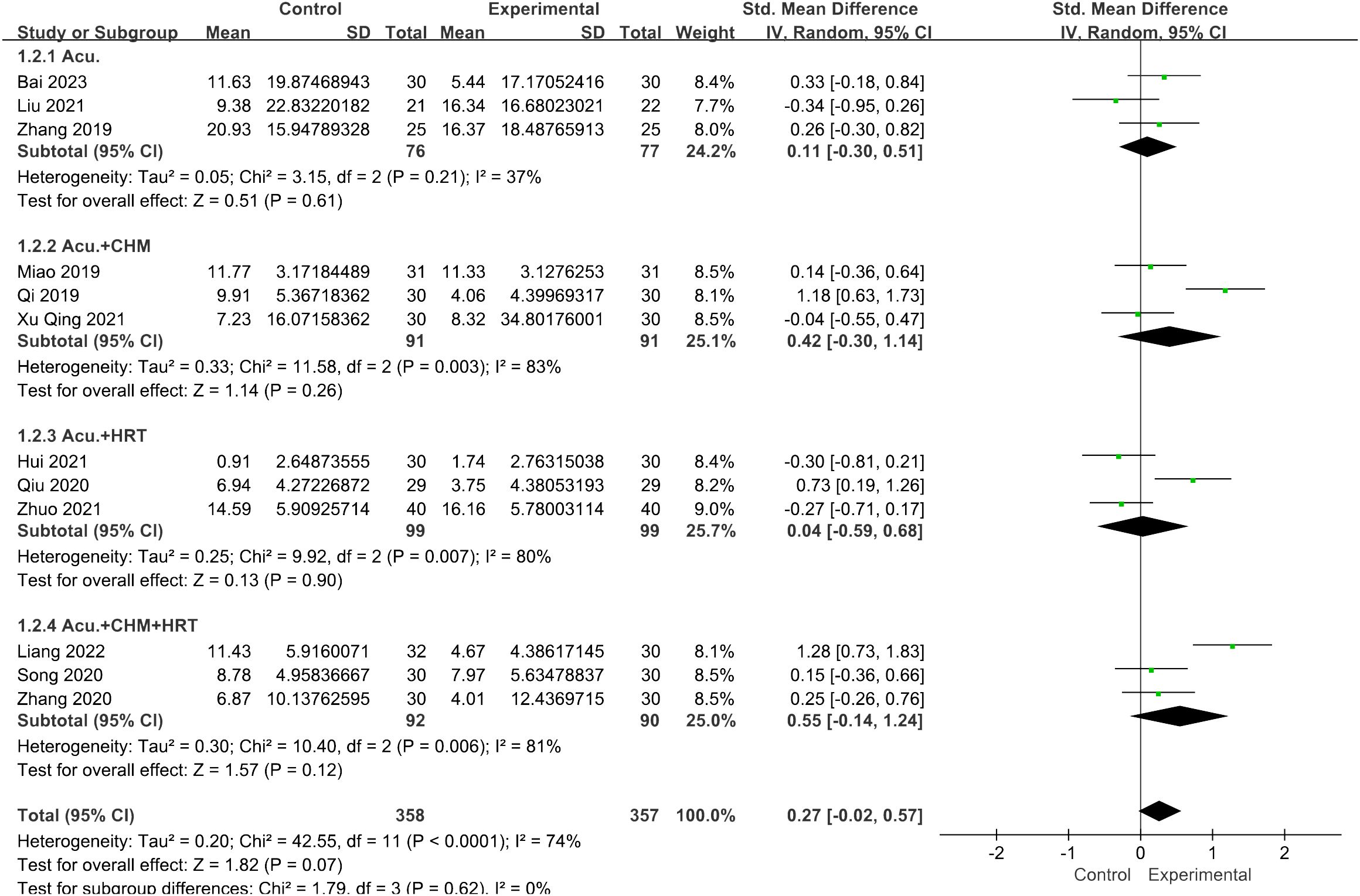

Twelve studies involving 715 patients focused on the LH levels. Compared with the control groups, the acupuncture group had no advantage [SMD = 0.27, 95% CI (−0.02, 0.57), I2 = 74%, p = 0.07] (Figure 4). The robustness of the combined findings was confirmed through sensitivity analysis.

Figure 4 Forest plot illustrating the relationship between LH levels and acupuncture therapy.

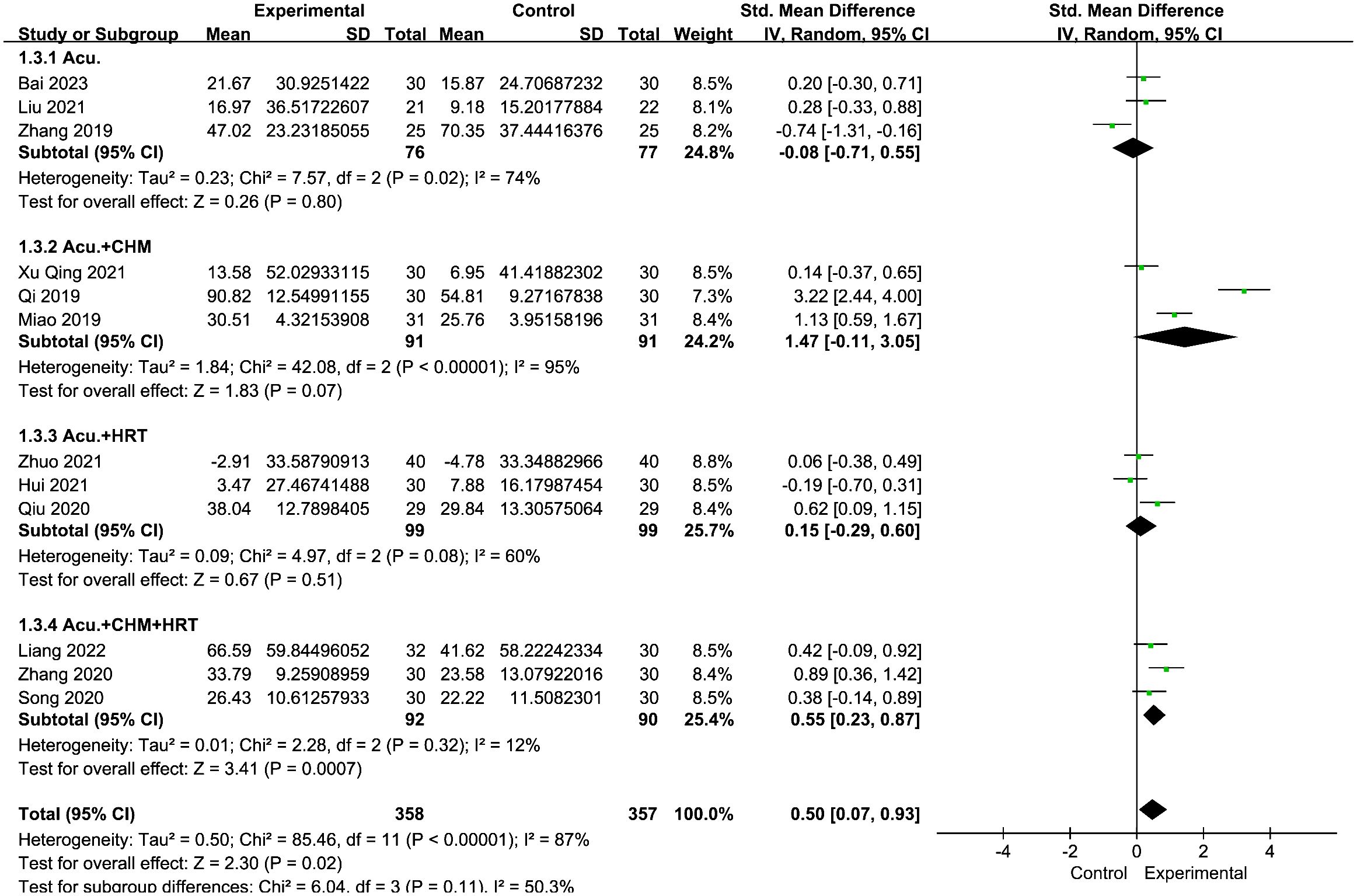

3.4.3 Estradiol levels

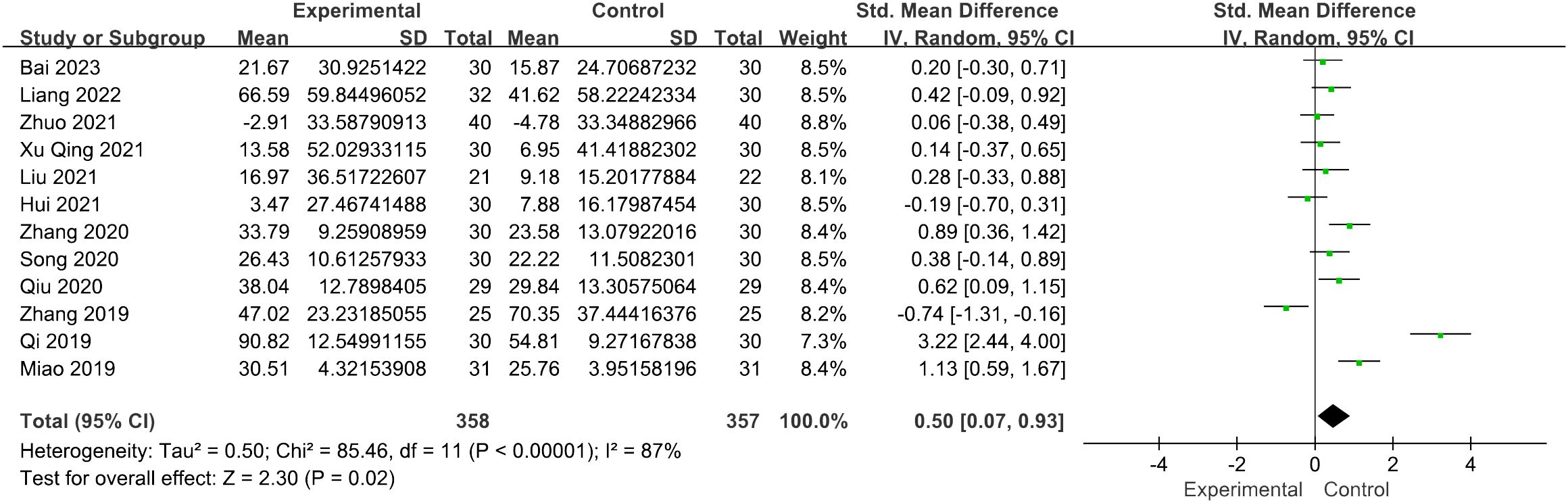

The evaluation of the impact of acupuncture on estradiol levels yielded 12 RCTs with a total of 715 individuals. It showed a statistically significant connection between the function of acupuncture and the improvement in estradiol levels [SMD = 0.50, 95% CI (0.07, 0.93), I2 = 87%, p = 0.02] (Figure 5). The pooled estimates remained unaffected by any individual study, as confirmed through the sensitivity analysis.

Figure 5 Forest plot illustrating the relationship between E2 levels and acupuncture therapy.

3.4.4 AMH levels

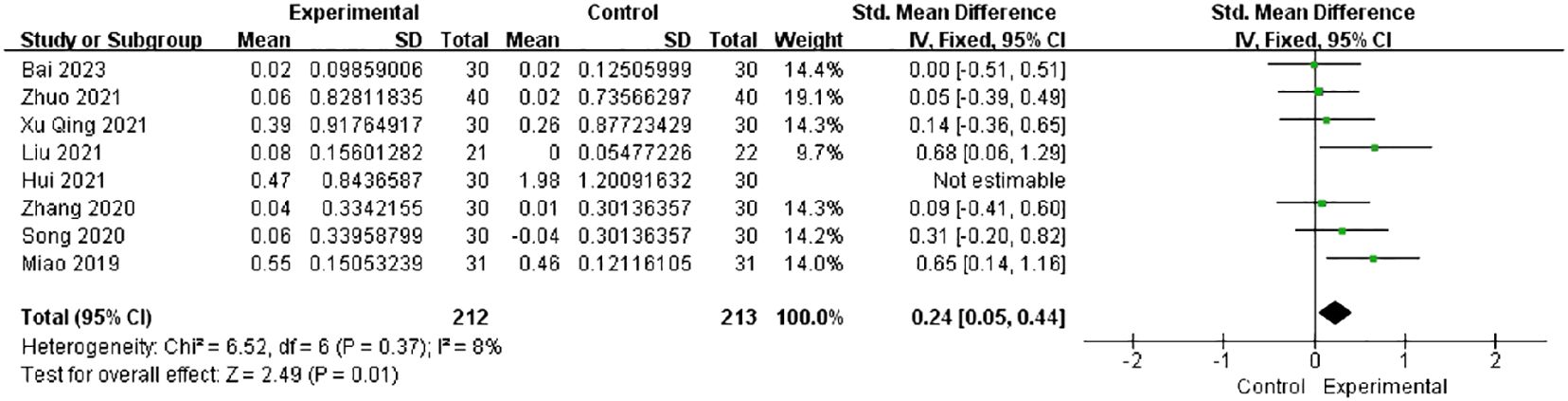

Among all studies, only eight studies reported the AMH levels. The heterogeneity dropped from 81% to 8% after the exclusion of one study (26) in the sensitivity analysis. The combined findings of seven trials with 212 individuals showed a significant increase in the AMH levels [SMD = 0.24, 95% CI (0.05, 0.44), I2 = 8%, p = 0.01] (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Forest plot illustrating the relationship between AMH levels and acupuncture therapy.

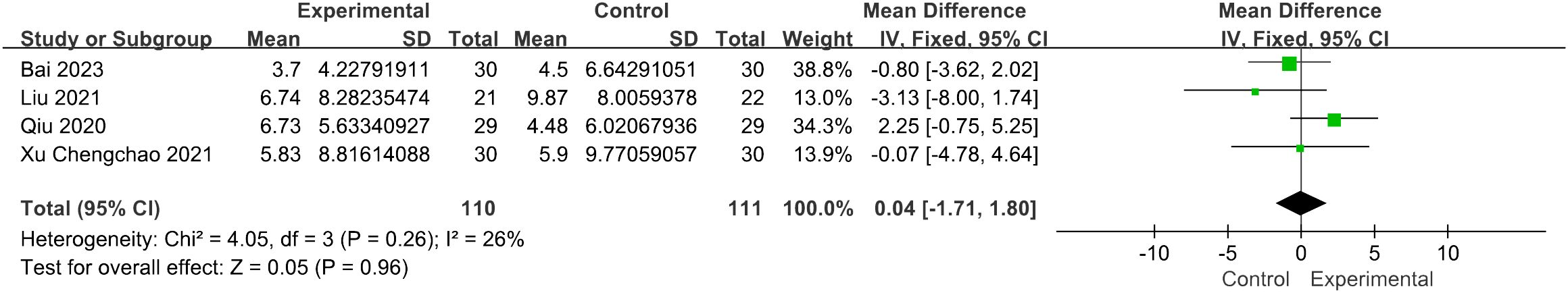

3.4.5 KI score

Four studies reported the modified KI score (39). The results of the fixed-effects model analysis indicated that there was no statistically significant difference between the control group and the acupuncture therapy group [MD = 0.04, 95% CI (−1.71, 1.80), I2 = 26%, p = 0.96] (Figure 7).

Figure 7 Forest plot illustrating the relationship between KI score and acupuncture therapy.

3.4.6 Antral follicle count

This meta-analysis of the antral follicle count (AFC) result contained 111 participants from a total of four studies. The pooled result revealed that the effects of acupuncture did not exhibit a significant difference from others [MD = 0.38, 95% CI (−0.73, 1.49), I2 = 89, p = 0.50] (Figure 8). Furthermore, following the sensitivity analysis, the outcomes remained unchanged.

Figure 8 Forest plot illustrating the relationship between AFC and acupuncture therapy.

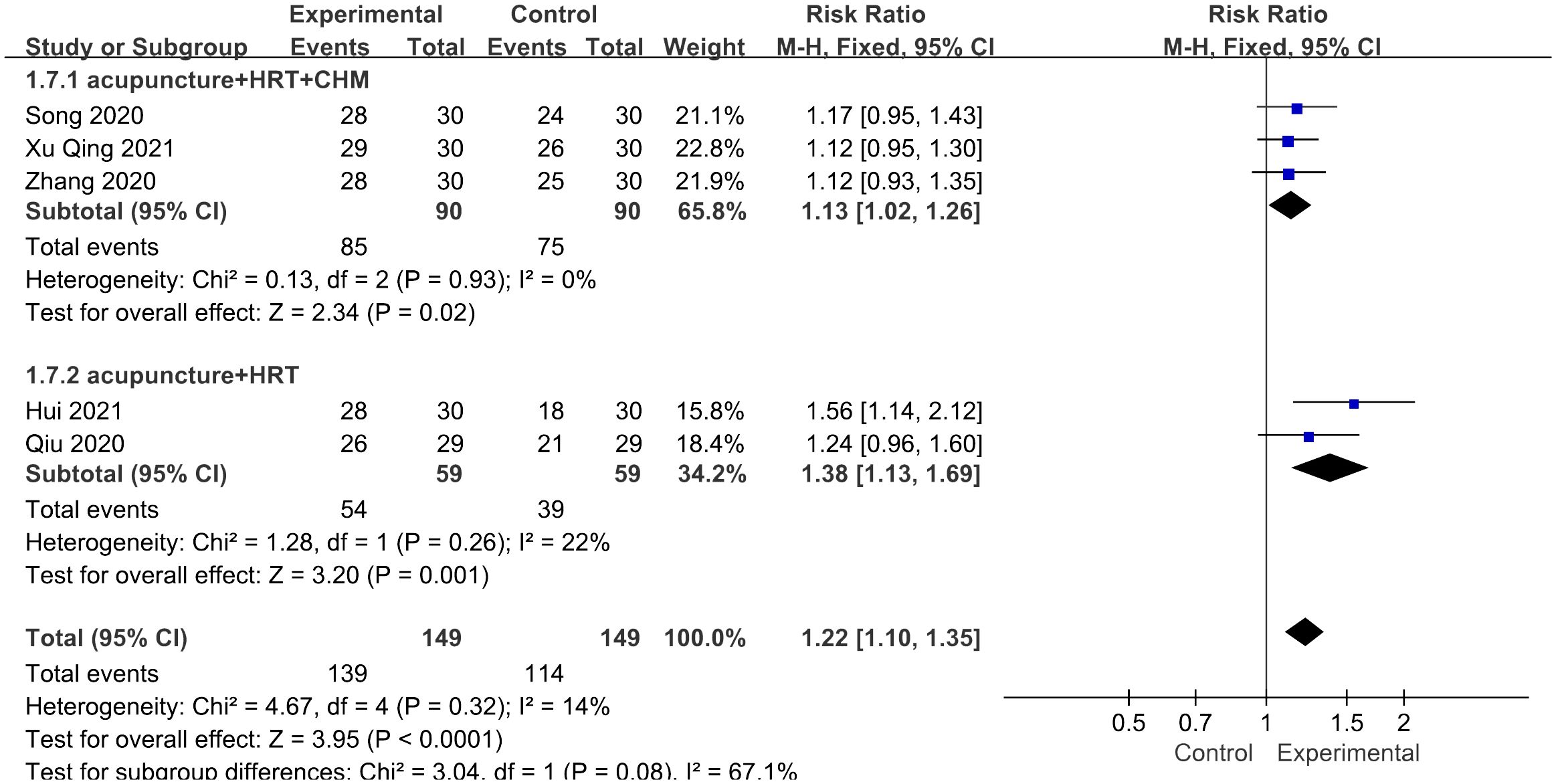

3.4.7 Total effective rate

Five studies assessed the overall effective rate (26, 30–32, 35), sticking to the same score scale including the menstrual cycle, menstrual blood volume, and general symptoms, such as palpitation and sleeplessness. Pretreatment and posttreatment evaluations were conducted, revealing a notable increase of 30% or more in symptom amelioration, thereby indicating effectiveness. The study results indicated that patients who received acupuncture treatment had a higher overall effective rate compared with those who did not receive acupuncture treatment [RR = 1.22, 95% CI (1.10, 1.35), I2 = 14%, p < 0.01] (Figure 9). The figure revealed low heterogeneity.

Figure 9 Forest plot illustrating the relationship between total effective rate and acupuncture therapy.

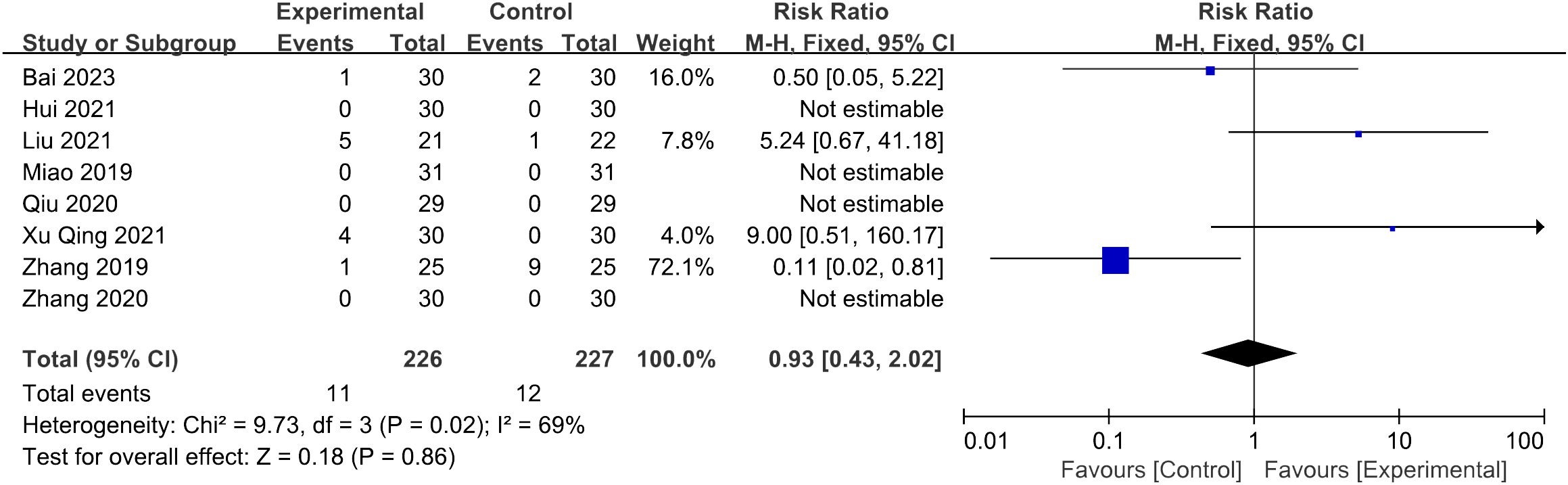

3.4.8 Adverse effect

Nine of the thirteen studies reported the situation of adverse effects: five of them reported adverse effects (29, 31, 33, 35, 38), while the remaining four documented no adverse effects (26, 27, 30, 32). One study reporting abdominal distension was excluded due to insufficient detailed description (31), while the following statistics included eight studies (26, 27, 29, 30, 32, 33, 35, 38). Among 226 patients in the trial groups, 11 cases of adverse events were reported, consisting of nine cases of subcutaneous hemorrhage (33, 35, 38), one case of breast distending pain (29), and one case of needle sticking (35). In the control groups, 12 adverse events were reported in 227 patients, consisting of five cases of stomach discomfort (29, 33), five cases of breast distending pain (29), and two episodes of menostaxis (38). Meta-analysis showed that the difference between the two groups lacks statistical significance (p = 0.86 > 0.05) (Figure 10).

Figure 10 Forest plot illustrating the relationship between adverse effect and acupuncture therapy.

3.5 Subgroup analysis

Due to three pooled results indicating significant heterogeneity (I2 > 60%) in the levels of FSH, LH, and estradiol, subgroup analysis was conducted based on various types of interventions.

3.5.1 FSH and LH levels

In the subgroup analysis for FSH levels, the pooled result revealed that both the acupuncture combined with CHM and HRT group [SMD = 1.02, 95% CI (0.52, 1.51), I2 = 60%, p < 0.0001] and the acupuncture with CHM group [SMD = 4.59, 95% CI (1.53, 7.65), I2 = 98%, p = 0.003] exhibited greater efficacy in lowering FSH levels compared with the non-acupuncture group (Figure 11). However, for the LH levels, no decrease in heterogeneity was observed during the subgroup analysis (Figure 12).

Figure 11 Forest plot illustrating the relationship between FSH levels and acupuncture therapy with subgroup analysis.

Figure 12 Forest plot illustrating the relationship between LH levels and acupuncture therapy with subgroup analysis.

3.5.2 Estradiol levels

The meta-analysis indicated that the acupuncture with CHM and HRT group outperformed the control groups [SMD = 0.55, 95% CI (0.23, 0.87), I2 = 12%, p = 0.0007] (Figure 13). High-level heterogeneity was seen in the remaining three subcategories, including nine journals. Rather than using a meta-analysis, a qualitative description was employed. Out of the nine investigations, three (28–30) demonstrated an increase in estradiol levels of the trial groups following treatment, surpassing those of the control groups (p < 0.05). The remaining six (26, 27, 35–38) investigations revealed no difference between the two groups (p > 0.05).

Figure 13 Forest plot illustrating the relationship between E2 levels and acupuncture therapy with subgroup analysis.

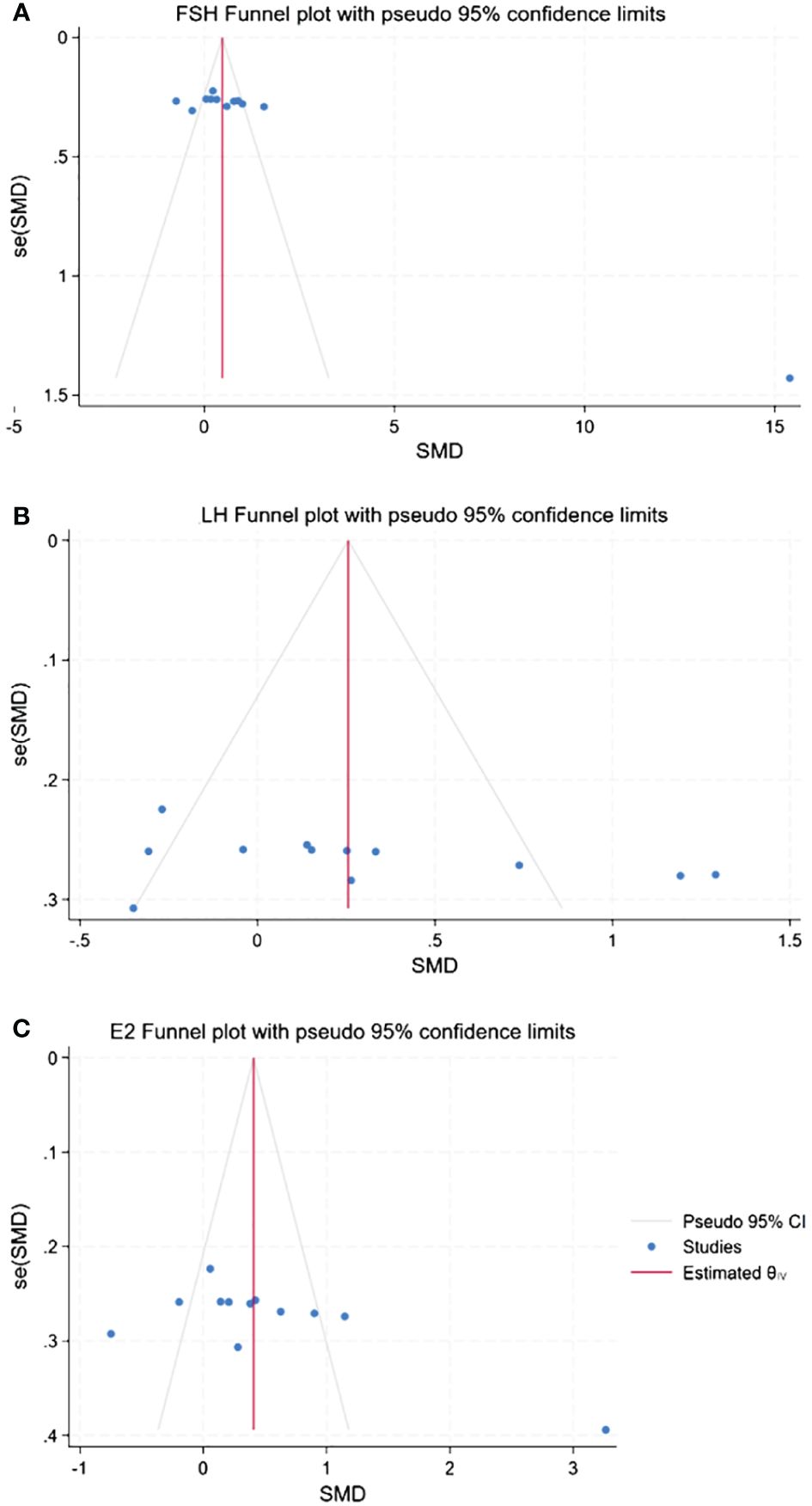

3.6 Publication bias

The presence of publication bias was assessed using Begg’s tests, with a minimum of 10 studies being included in the analysis. There was no apparent asymmetry in the funnel plots, as shown in Figure 14. Begg’s test for FSH (p = 0.06), LH (p = 0.06), and E2 (p = 0.09) was not significant for publication bias in this meta-analysis due to p >0.05.

Figure 14 Funnel plots of publication bias. (A) Publication bias of FSH. (B) Publication bias of LH. (C) Publication bias of E2.

4 Discussion

This study represents the inaugural meta-analysis evaluating the clinical efficacy of acupuncture for POI, employing FSH >25 IU/L as the diagnostic criterion. In this investigation, we incorporated a total of 13 RCTs, involving 775 patients, to scrutinize the efficacy of acupuncture for POI. The findings are succinctly presented as follows: 1) sex hormones—acupuncture demonstrated a significant reduction in FSH levels and an increase in AMH and E2 levels in POI patients, with negligible impact on LH levels. 2) Follicular development status—following the reduction of heterogeneity, acupuncture yielded a significant improvement in AMH levels, while no discernible difference was observed in AFC. 3) Climacteric symptoms—patients subjected to acupuncture exhibited a higher overall effective rate compared with their counterparts without acupuncture. However, the acupuncture group manifested no improvement in the Kupperman index, and the difference in adverse effects between the two groups lacked statistical significance.

FSH possesses the capability to enhance follicular development and stimulate estrogen secretion. Elevated FSH levels are associated with excessive follicular depletion, culminating in diminished follicular reserve. Lower FSH levels can enhance fertility probabilities. Serving as a biomarker of follicular development, estrogen not only protects the cardiovascular system and nerves but also prevents the risk of bone rarefaction. Addressing estrogen deficiency effectively markedly improves the quality of life for POI patients. AMH can prevent premature follicular depletion by inhibiting the recruitment of primordial follicles. According to our findings, acupuncture demonstrated the potential to lower FSH levels, elevate E2 and AMH levels, and alleviate associated symptoms. Preantral follicle development took 85 days to mature, during which time the follicles underwent continuous growth (grades 1 to 4) and exponential growth (grades 5 to 8). The findings of the study suggest that acupuncture has the potential to decrease FSH levels, increase E2 and AMH levels, and alleviate associated symptoms. However, due to the long time required for follicle development from the preantral follicle to the antral follicle, which can be observed by B-ultrasound, this study did not find any benefit of acupuncture treatment on antral follicle-related outcomes.

In contrast to previous systematic reviews, we adhered to the latest diagnostic criteria for POI as outlined by the ESHRE. Additionally, the intervention window was advanced. The literature incorporated into this study was not considered in prior relevant articles. Consistent with earlier discoveries (40, 41), our findings demonstrate the efficacy of acupuncture in lowering serum FSH levels and increasing E2 levels. Limited research has focused on the isolated effects of acupuncture. Our study revealed that acupuncture has the potential to elevate AMH levels and the overall effective rate, exerting positive effects on menstrual disorders and perimenopausal symptoms.

Acupuncture, emerging as a novel therapy for POI, has been demonstrated to modulate a diverse array of cellular processes and pathways. In another investigation, acupuncture exhibited the capacity to stimulate Bcl-2 and diminish Bax expression in ovarian tissues, thereby mitigating granulosa cell apoptosis and impeding primordial follicle loss through the induction of antioxidant and anti-apoptotic systems (42). Additionally, Zhang et al. (43) unveiled that electroacupuncture could potentially inhibit the phosphorylation of proteins in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, leading to the restoration of serum levels of AMH, E2, FSH, and LH, along with the proliferation of small follicles. Remarkably, electroacupuncture exhibited the potential to regulate characteristic metabolites linked to energy and neurotransmitter metabolism in the liver and kidney, thereby enhancing the menstrual cycle in the participants (44). Moreover, a recent experiment revealed that electroacupuncture could potentially stabilize hormone levels and mitigate follicular atresia by upregulating the expression of CDK6/CCND1 in murine ovarian granulosa cells (OGCs) (45).

The limitations of this systematic study are as follows: firstly, the clinical effect is susceptible to various factors such as acupoint selection, stimulation intensity, qi generation, and acupuncture techniques, lacking uniformity and objectivity at present. It may contribute to the observed heterogeneity, and no significant improvement was achieved in the subgroup analysis. Furthermore, due to limitations in the source studies, pregnancy outcomes cannot be assessed though serving as a crucial concern for reproductive-aged women with POI. Individuals with POI may experience anxiety, depression, and dyssomnia (46). Although acupuncture has demonstrated benefits for ovarian function, its impact on physical and psychological health or quality of life remains unexplored. Additionally, the thickness of the endometrium should be monitored in time after the rise of estrogen, and if necessary, progesterone should be used to transform the endometrium. Moreover, a majority of the included studies lacked explicit descriptions of double-blind procedures, resulting in methodological shortcomings. Nevertheless, the nature of acupuncture involves mutual interaction between the physician and the patient, making the application of a blinding approach challenging. Therefore, our study represents the inaugural meta-analysis and systematic review of RCTs adhering to the 2016 ESHRE criteria, with a specific focus on acupuncture for POI patients. Despite these limitations, future efforts should involve larger and higher-quality RCTs incorporating essential acupuncture outcomes to comprehensively assess its current clinical efficacy.

5 Conclusion

Considering the research findings, acupuncture emerges as a potentially efficacious alternative therapy for the treatment of POI, particularly in light of the existing deficiencies in HRT. However, the quality of evidence remains constrained due to the significant heterogeneity and the small sample effect. Future research is imperative to substantiate the efficacy of acupuncture in the treatment of POI, necessitating meticulously designed, large-scale and multicenter RCTs.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

HC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing. XL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing. SL: Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. PL: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. CC: Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. LX: Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study received funding from the Three-Year Action Plan for Further Accelerating the Development of Traditional Chinese Medicine Inheritance and Innovation in Shanghai (2021–2023) [grant number ZY(2021–2023)-0209–01] and the Shanghai Science and Technology Commission under Grant 23Y21920300. Clinical study of internal adjustment and external treatment combined with prevention and treatment of mild and medium positive Omicron infection during rehabilitation (2022-KY-ZYY-07).

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to Mengxin Ye and Huirong Gao for their assistance in language editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fendo.2024.1361573/full#supplementary-material

References

1. European Society for Human R, Embryology Guideline Group on POI, Webber L, Davies M, Anderson R, Bartlett J, et al. ESHRE Guideline: management of women with premature ovarian insufficiency. Hum Reprod. (2016) 31:926–37. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew027

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Zhou Y, Jin Y, Wu T, Wang Y, Dong Y, Chen P, et al. New insights on mitochondrial heteroplasmy observed in ovarian diseases. J Adv Res. (2023). doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2023.11.033

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Zhang Q, Zhang W, Wu X, Ke H, Qin Y, Zhao S, et al. Homozygous missense variant in MEIOSIN causes premature ovarian insufficiency. Hum Reprod. (2023) 38:ii47–56. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dead084

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Cattoni A, Parissone F, Porcari I, Molinari S, Masera N, Franchi M, et al. Hormonal replacement therapy in adolescents and young women with chemo- or radio-induced premature ovarian insufficiency: Practical recommendations. Blood Rev. (2021) 45:100730. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2020.100730

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Chemaitilly W, Li Z, Krasin MJ, Brooke RJ, Wilson CL, Green DM, et al. Premature ovarian insufficiency in childhood cancer survivors: A report from the st. Jude lifetime cohort. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2017) 102:2242–50. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016–3723

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

6. Hamoda H, Sharma A. Premature ovarian insufficiency, early menopause, and induced menopause. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2024) 38(1):101823. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2023.101823

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

7. Menopause Subgroup CSoO, Gynecology CMA. [Consensus of clinical diagnosis and treatment of premature ovarian insufficiency (2023)]. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. (2023) 58:721–8. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112141–20230316–00122

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

8. Gunning M, Meun C, van Rijn B, Daan N, Roeters van Lennep J, Appelman Y, et al. The cardiovascular risk profile of middle age women previously diagnosed with premature ovarian insufficiency: A case-control study. PLoS One. (2020) 15:e0229576. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229576

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

10. Ishizuka B. Current understanding of the etiology, symptomatology, and treatment options in premature ovarian insufficiency (POI). Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2021) 12:626924. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.626924

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Armeni E, Paschou SA, Goulis DG, Lambrinoudaki I. Hormone therapy regimens for managing the menopause and premature ovarian insufficiency. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2021) 35:101561. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2021.101561

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

12. Cuzick J, Chu K, Keevil B, Brentnall AR, Howell A, Zdenkowski N, et al. Effect of baseline oestradiol serum concentration on the efficacy of anastrozole for preventing breast cancer in postmenopausal women at high risk: a case-control study of the IBIS-II prevention trial. Lancet Oncol. (2024) 25:108–16. doi: 10.1016/S1470–2045(23)00578–8

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Kalenga CZ, Metcalfe A, Robert M, Nerenberg KA, MacRae JM, Ahmed SB. Association between the route of administration and formulation of estrogen therapy and hypertension risk in postmenopausal women: A prospective population-based study. Hypertension. (2023) 80:1463–73. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.122.19938

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

14. Mohammed K, Abu Dabrh AM, Benkhadra K, Al Nofal A, Carranza Leon BG, Prokop LJ, et al. Oral vs transdermal estrogen therapy and vascular events: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2015) 100:4012–20. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015–2237

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

15. Booyens RM, Engelbrecht AM, Strauss L, Pretorius E. To clot, or not to clot: The dilemma of hormone treatment options for menopause. Thromb Res. (2022) 218:99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2022.08.016

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

16. Yang Q, Zhu L, Jin L. Human follicle in vitro culture including activation, growth, and maturation: A review of research progress. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2020) 11:548. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.00548

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

17. Kawamura K, Cheng Y, Suzuki N, Deguchi M, Sato Y, Takae S, et al. Hippo signaling disruption and Akt stimulation of ovarian follicles for infertility treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2013) 110:17474–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312830110

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

18. Zhai J, Yao G, Dong F, Bu Z, Cheng Y, Sato Y, et al. In vitro activation of follicles and fresh tissue auto-transplantation in primary ovarian insufficiency patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2016) 101:4405–12. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016–1589

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

19. Chen ZJ, Tian Q, Qiao J. [Chinese expert consensus on premature ovarian insufficiency]. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. (2017) 52:577–81. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529–567X.2017.09.001

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

20. Zhang S, Yahaya BH, Pan Y, Liu Y, Lin J. Menstrual blood-derived endometrial stem cell, a unique and promising alternative in the stem cell-based therapy for chemotherapy-induced premature ovarian insufficiency. Stem Cell Res Ther. (2023) 14:327. doi: 10.1186/s13287-023-03551-w

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

21. Yang L, Yang W, Sun M, Luo L, Li HR, Miao R, et al. Meta analysis of ovulation induction effect and pregnancy outcome of acupuncture & moxibustion combined with clomiphene in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2023) 14:1261016. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1261016

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

22. Lin G, Liu X, Cong C, Chen S, Xu L. Clinical efficacy of acupuncture for diminished ovarian reserve: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2023) 14:1136121. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1136121

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

23. Page M, McKenzie J, Bossuyt P, Boutron I, Hoffmann T, Mulrow C, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ(Clinical Res ed.). (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

24. Hugh M, Altman D, Hammerschlag R, Hammerschlag R, Li Y, Wu T, et al. STRICTA Revision Group. [Revised Standards for Reporting Interventions in Clinical Trials of Acupuncture (STRICTA): extending the CONSORT statement (Chinese version)]. Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Bao. (2010) 8:804–18. doi: 10.3736/jcim20100902

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

25. Li P, Zhang Y, Li F, Cai F, Xiao B, Yang H. The efficacy of electroacupuncture in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv Biol (Weinh). (2023) 7:e2200304. doi: 10.1002/adbi.20220030

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

26. Hui J, Yang P, Wang Y, Zhao X, Li B, Xiao Y, et al. Efficacy observation of tiao ren bu shen needling method plus western medication for premature ovarian. Shanghai J Acu-mox. (2021) 40:551–4. doi: 10.13460/j.issn.1005–0957.2021.05.0551

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

27. Miao Y. Clinical study on the treatment of premature ovarian insufficiency of kidney-deficiency and liver stagnation type by combination of acupuncture and medicine. Hubei,China: Hubei University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2019) 4:128–9.

Google Scholar

28. Qi L, Su T, Yang Y, Jiang X. Clinical effect of acupuncture in the treatment of 30 patients with premature ovarian insufficiency. Clin Res Practice. (2019) 4:128–9. doi: 10.19347/j.cnki.2096–1413.201929055

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

29. Zhang J, Liu Y, Deng R, Guo Y, Yan B, Chen P, et al. Observation on therapeutic effect of “Tiaoren Tongdu acupuncture” on premature ovarian insufficiency of kidney deficiency. Chin acupuncture moxibustion. (2019) 39:579–82. doi: 10.13703/j.0255–2930.2019.06.003

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

30. Qiu J. Clinical observation on abdominal acupuncture combined with femoston in the treatment of premature ovarian insufficiency of kidney deficiency type. Fujian,China: Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2020).

Google Scholar

31. Song J. Clinical study on the treatmet of premature ovarian insufficiency in the kidney deficiency and blood stasis type by combining acupuncture with traditional Chinese medicine. Liaoning,China: Liaoning University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2020).

Google Scholar

32. Zhang S. Clinical observation on the combination of Chinese and Western medicine and acupuncture in treating patients with premature ovarian insufficiency of kidney deficiency and liver depression syndrome. Liaoning,China: Liaoning University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2020).

Google Scholar

33. Liu X. Metabolomics of Serum Studies on the impact of acupuncture combined with hormone replacement therapy on sex hormone-related metabolites and metabolic pathways in individuals with premature ovarian insufficiency. Hunan,China: Hunan University of Chinese Medicine (2021).

Google Scholar

34. Xu C, Li H, Fang Y, Bai T, Yu X. Effect of regulating menstruation and promoting pregnancy acupuncture therapy on negative emotion in patients with premature ovarian insufficiency. Chin Acupuncture Moxibustion. (2021) 41:279–82. doi: 10.13703/j.0255–2930.20200307–0004

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

35. Xu Q. Clinical study on acupuncture combined with traditional Chinese medicine in the treatment of premature ovarian insufficiency due to liver and kidney Yin deficiency. Liaoning,China: Liaoning University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2021).

Google Scholar

36. Zhuo Y, Huang X, Huang Y, Wu J. Effect of regulating menstruation and promoting pregnancy acupuncture in the treatment of patients with premature ovarian insufficiency undergoing in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. China Med Herald. (2021) 18:125-8,132.

Google Scholar

37. Liang S, Huang X, He D. Clinical observation of combined acupuncture and medicine in the treatment of premature ovarian insufficiency with kidney deficiency and liver stagnation syndrome. Lishizhen Med Materia Med Res. (2022) 33:2682–4. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1008–0805.2022.11.31

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

38. Bai T, Li H. Efficacy of medical moxibustion at baliao points combined with regulating menstruation to promote pregnancy acupuncture on premature ovarian insufficiency of spleen and kidney yang deficiency. Shangdong J Traditional Chin Med. (2023) 42:1074–9. doi: 10.16295/j.cnki.0257–358x.2023.10.010

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

39. Tao M, Shao H, Li C, Teng Y. Correlation between the modified Kupperman Index and the Menopause Rating Scale in Chinese women. Patient Prefer Adherence. (2013) 7:223–9. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S42852

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

40. Li Y, Xia G, Tan Y, Shuai J. Acupoint stimulation and Chinese herbal medicines for the treatment of premature ovarian insufficiency: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther Clin Pract. (2020) 41:101244. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2020.101244

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

41. Li H, Zhang J, Chen W. Dissecting the efficacy of the use of acupuncture and Chinese herbal medicine for the treatment of premature ovarian insufficiency (POI): A systematic review and metaanalysis. Heliyon. (2023) 9:e20498. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20498

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

42. Tan R, He Y, Zhang S, Pu D, Wu J. Effect of transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation on protecting against radiotherapy- induced ovarian damage in mice. J Ovarian Res. (2019) 12:65. doi: 10.1186/s13048–019-0541–1

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

43. Zhang H, Qin F, Liu A, Sun Q, Wang Q, Xie S, et al. Electro-acupuncture attenuates the mice premature ovarian failure via mediating PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Life Sci. (2019) 217:169–75. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2018.11.059

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

44. Chen M, He Q, Guo J, Wu Q, Zhang Q, Yau Y, et al. Electro-acupuncture regulates metabolic disorders of the liver and kidney in premature ovarian failure mice. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2022) 13:882214. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.882214

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

45. Geng Z, Liu P, Yuan L, Zhang K, Lin J, Nie X, et al. Electroacupuncture attenuates ac4C modification of P16 mRNA in the ovarian granulosa cells of a mouse model premature ovarian failure. Acupunct Med. (2023) 41:27–37. doi: 10.1177/09645284221085284

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

46. Xi D, Chen B, Tao H, Xu Y, Chen G. The risk of depressive and anxiety symptoms in women with premature ovarian insufficiency: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Womens Ment Health. (2023) 26:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00737–022-01289–7

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar