Meaning of words Theologian Who comes to mind? A devout priest prostrating himself in prayer on the floor of his cell? A faithful soup kitchen volunteer? Or a serious type in tweed swapping metaphysical jargon with other bookish people? Probably the last.

A favorite phrase of my seminary professors was, “The study of theology needs to be connected to worship and prayer. It needs to actually shape your life.” The need for constant reaffirmation of this important teaching points to a contemporary reality. Theology and spirituality, once two sides of the same coin, are now often treated as different currencies. One has become an academic discipline, the other a bag of tools for dealing with life’s difficulties. How did we get to a theology without spirituality? And how do we get back to a concept and practice of theology that is necessarily godly, not merely optional or ideal?

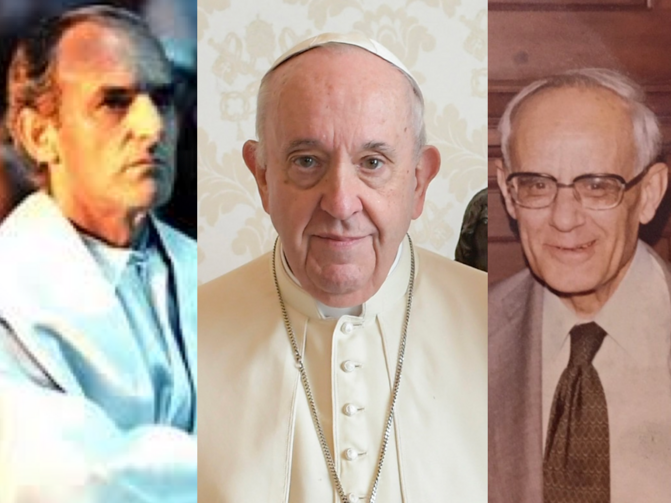

in Theological renewalJ. Matthew Ashley examines Ignatian spirituality and its illustrations in the lives and theology of three 20th-century Jesuits: Karl Rahner, Ignacio Eliascuria, and Pope Francis.

in Theological renewalJ. Matthew Ashley notes that as the divide between academic theology and spirituality deepens, there is a common sense among Christians today that theology has little relevance to their lives. But he argues that when we enter into a dynamic relationship with spirituality (and vice versa), the work of theology becomes deeply relevant to our lives and essential to following Christ at every level. It becomes a “way of life,” or part of the life of faith.

This integration is mutually beneficial: Academic Theology Sands Spirituality has become nothing more than a “jargon for experts” (to borrow French philosopher Pierre Hadot’s description of philosophy); Sands Jesuit theology is in danger of slipping into “provincialism, vague romanticism, or fanaticism.”To demonstrate this relationship and the lives it produces, Ashley turns to Ignatian spirituality and its illustrations in the lives and theology of three 20th-century Jesuits: Karl Rahner, Ignacio Ellacuria, and Pope Francis.

By examining in detail how each Jesuit’s thought and work are guided by the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola, the reader begins to get a sense of the scope of the reform Ashley advocates. Connected with a deeper source of spirituality, theology is not just a technical term but an experience of God, a force for good capable of mobilizing individuals and entire societies. This relationship between spirituality and theology is highly productive, not just for each other, but, as Ashley shows throughout, for all of us. Theological renewal“For the church and the surrounding community.”

Ashley takes Ignatius as the starting point and conceptual fulcrum of the book, not because he thinks that his spirituality alone can (or has already) done the work of theological renewal, but because of his “special aptitude” for the problems at hand: Ignatius lived at the beginning of modernity and thus had to wrestle with many of the same conditions that theologians grapple with today. Ashley further argues that these conditions created a rift between theology and spirituality; he summarizes them as modern individualism, the affirmation of everyday life, and the acceleration of life’s transience.

Ashley explains that these conditions of modernity have given rise to the very concept of spirituality as we know it. The first condition, individualism, can be seen in modern spirituality’s obsession with connecting the individual to an ever-elusive “true self.” The second condition, the affirmation of everyday life, is evident in what theologian and historian Bernard McGinn calls the “democratization of Christian mysticism,” and is even evident today in concepts such as “sexual spirituality” and “shopping spirituality.” And the third condition, in keeping with the transience of modernity, modern spirituality emphasizes portability, making us “like turtles with their shelter on their backs,” Ashley says.

Ashley argues that Ignatian spirituality reflects these conditions of modernity but is not limited by them. For example, Ignatius addresses the Spiritual Exercises to the individual but always locates them within the broader context of the Church and salvation history. Moreover, Ignatian theological anthropology does not amount to what Charles Taylor calls the modern “buffered self,” but rather to a thoroughly premodern “porous self.” Ignatian detachment is not a means of escape but rather a means to more fully imitate and embrace the reality of Jesus. Moreover, his affirmation of the everyday does not lower his vision of spirituality but raises the bar for all, regardless of occupation or vocation. Finally, the rootlessness of Ignatian spirituality is “consciously chosen,” leading to mobilization rather than fragmentation, a simultaneous presence in secular time and in salvation history.

The result is not the chaotic frenzy of modernity, but a sense of belonging brought about by God’s unifying love. Ashley summarizes the modern self as one self at work. Labor isIgnatius reorients Christians to the work of God, and the alienation of individual labor so poignantly described by Marx is redeemed by the united labor of God, which invites the participation of all, as exemplified by the work of Rahner, Ellacuria, and Francisco. Rather than merely a “refuge” for a fragmented spirituality, Ignatius offers these Jesuit theologians a “source of vision.” This is essential, because, as Ashley points out, “when vision is lost, theology fails.”

Ashley sums up the modern self as the self at work. Labor isIgnatius reorients Christians to the work of God, in which the alienation of individual labor is redeemed by the unitary labor of God.

Each person emphasizes different aspects of the Spiritual Exercises according to his own particular context and interests. For example, Rahner was primarily concerned with Taylor’s “buffered self” and the isolated world of modern secularism. He therefore emphasized Ignatian mysticism and was convinced that Christians could only survive in the modern world by paying attention to the mystical presence of God within it and becoming mystics themselves.

Ellacuría approached exercise with an emphasis on how this mystical encounter changes the way we see and participate in history, rather than on the liberation of the secularized individual. For him, exercise is useful in cultivating an appropriate emotional response to the current historical moment by cultivating an appropriate feeling for the historical significance of Jesus. This “orthopathy” (right feeling), he believed, “is at the root of healing the Christian social imagination and discerning in which historical acts we actually encounter God.”

Finally, the influence of Ignatius on Pope Francis is evident in the emphasis he places on pastoral care. He stresses the importance of encountering Jesus in his training, experiencing his mercy, receiving his comfort and being able to offer it to others, and he calls the Church to do so through his own example. Thus, Pope Francis sees in Ignatius that the Church’s mission and identity lies in going beyond the Church to reach the margins of society.

It is impossible to adequately describe these case studies in three short paragraphs. Ashley provides a very thorough portrayal of each of their lives and thought. He explores and outlines their intellectual and spiritual formations, how they approached the specific themes of the exercise, and the ways in which they used these to conceptualize and respond to the conditions of modernity that particularly interested them. Readers with varying degrees of familiarity with these three men will undoubtedly come away with a new appreciation for their thought and work.

The big results are Theological renewal A major feature of this book is that it offers a path toward a theological renewal that reflects and even welcomes contemporary pluralism. Rahner, Ellacuria, and Francisco do not agree on everything, and Ashley acknowledges that. But one of the underlying thesis of Ashley’s text is that because spirituality can cross cultural boundaries more easily than doctrinal issues or theological systems, theological differences are addressed more effectively when properly situated within strong spiritual traditions. Because spirituality “travels more easily,” addressing theological differences through spiritual traditions allows for “theological dialogue that goes beyond polemical rejection or laissez-faire relativism.”

While the division of theology and spirituality that Ashley focuses on is not itself new, the way he portrays its origins and traces responses from Ignatius to Francis takes a fresh approach. In reviving the relationship between theology and how we live in the world, Ashley does not simply present it in the abstract; he shows it is possible. He not only shows that a theological renewal is needed, but imagines what it might look like and allows readers to begin to imagine how this kind of renewal might take shape in their own theological traditions, their own contexts, and their own lives. The “creative alternatives” that this book offers are not silver bullets, but rather “sources of vision.”