Psychiatric Opinions in the Daily News

In yesterday’s column, I wrote that I was left feeling dazed and confused after the presidential debate, and other colleagues expressed similar reactions, with some saying they were “physically shocked,” “utterly unbelievable,” and “like a nightmare” on one side, and others expressing more positive emotional reactions.

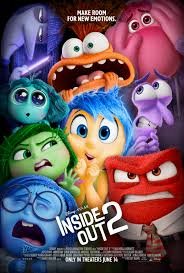

Thankfully, my new friend Al Simon came to the rescue. A week or two ago, he urged me to watch Inside Out 2, thinking that as a psychiatrist, I would be interested and wanted to see my reaction. Before I knew it, we went yesterday with our spouses.

I saw the original Inside Out about nine years ago. In that Pixar animated film, a nine-year-old girl named Riley moves with her parents from Minnesota to San Francisco. Her innermost feelings are expressed in the film as animated characters in a place called “Headquarters” – Joy, Sadness, Anger, Fear and Disgust. It was a creative, insightful, empathetic and compassionate portrayal of the impact emotions have on relationships.

That title was interesting to me, too, because a few years earlier I had written an unusual haiku about the ins and outs of our minds. I think it was published in the Houston Psychiatric Society newsletter. I remembered that line clearly:

Psychiatrist

Trying to change the inside

Outside ourselves

The sequel, which also depicts the change in neurons and memories through rising lines and marbles (which may mean “going crazy” mentally), is a huge hit with audiences and a psychiatric success. Now Riley is 13, an age when puberty brings increasing unhappiness, but in her case, it is made worse by having to move away from her two best friends and start a new high school. Moving forward in time, the friends are from different cultures and the girls play a fierce game of hockey.

As old emotions are temporarily stored in her psyche’s memory, new emotional core characters are added: anxiety, fatigue, envy, nostalgia, and embarrassment. In her efforts to make a good impression on her older students, anxiety dominates her joy and she becomes more selfish and less of a good person. She must finally grieve the losses of her past in order to move forward.

But as I told a friend later, the emotion that was missing for me was guilt. There seems to be a dark part of her mind that reminds me a little of past trauma, but it’s a side character. There’s little explanation for how and why she became a good person again. There’s no therapist nearby.

I am left wondering where the guilt was, or was there at all, in the presidential debates and among many politicians. Perhaps guilt is fading in our society at large. We know that sociopaths and excessive narcissists have no guilt.

There are more parallels to real life: conflicts are getting worse instead of being resolved; mental disorders are on the rise, especially among teens, and especially black women; and we are only just beginning to curb excessive cell phone use.

In movies, as in life, things sometimes pass by too quickly for us to comprehend, which is why I found myself wanting to watch this movie over and over again, and in that respect, maybe even discuss it as a group afterwards, as our two couples did over dinner.

I found the film therapeutic, as it appears to be aimed at teenagers, their teachers, and their parents. In that respect, it may be beneficial for patients, who may want to discuss it with their therapists. Understanding our emotions and the extent to which we can cognitively control them is difficult.

We older people might also benefit from watching this movie. We too can be helped by grieving what we have lost or are losing, such as people or a normal climate. As we start our lives over, we remember memories, especially those that are emotionally strong, both good and bad, but for some, memories are lost to dementia. Perhaps a sequel will follow us to our age, when we are losing neurons but gaining new connections of wisdom.

Dr. Moffic is an award-winning psychiatrist specializing in the cultural and ethical aspects of psychiatry, now retired and practicing as a private pro bono community psychiatrist. A prolific writer and speaker, he has written a weekday column titled “A Psychiatric Perspective on the Daily News” and a weekly video called “Psychiatry and Society” since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. He was selected as the 2024 recipient of the Abraham Halpern Humanitarian Award by the American Society of Social Psychiatry. He has been honored with the Administrative Award from the American Psychiatric Association in 2016, the one-time Hero of Public Psychiatry from the President of the General Assembly of the American Psychiatric Association in 2002, and the Exemplary Psychiatrist Award from the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill in 1991. He is an advocate and activist for mental health issues related to climate instability, physician burnout, and xenophobia. He is currently editing the final volume of Springer’s four-volume series on religion and psychiatry, “Islamophobia, Anti-Semitism, Christianity, and Now.” Eastern Religion and SpiritualityHe serves on the editorial board. Psychiatry Times.