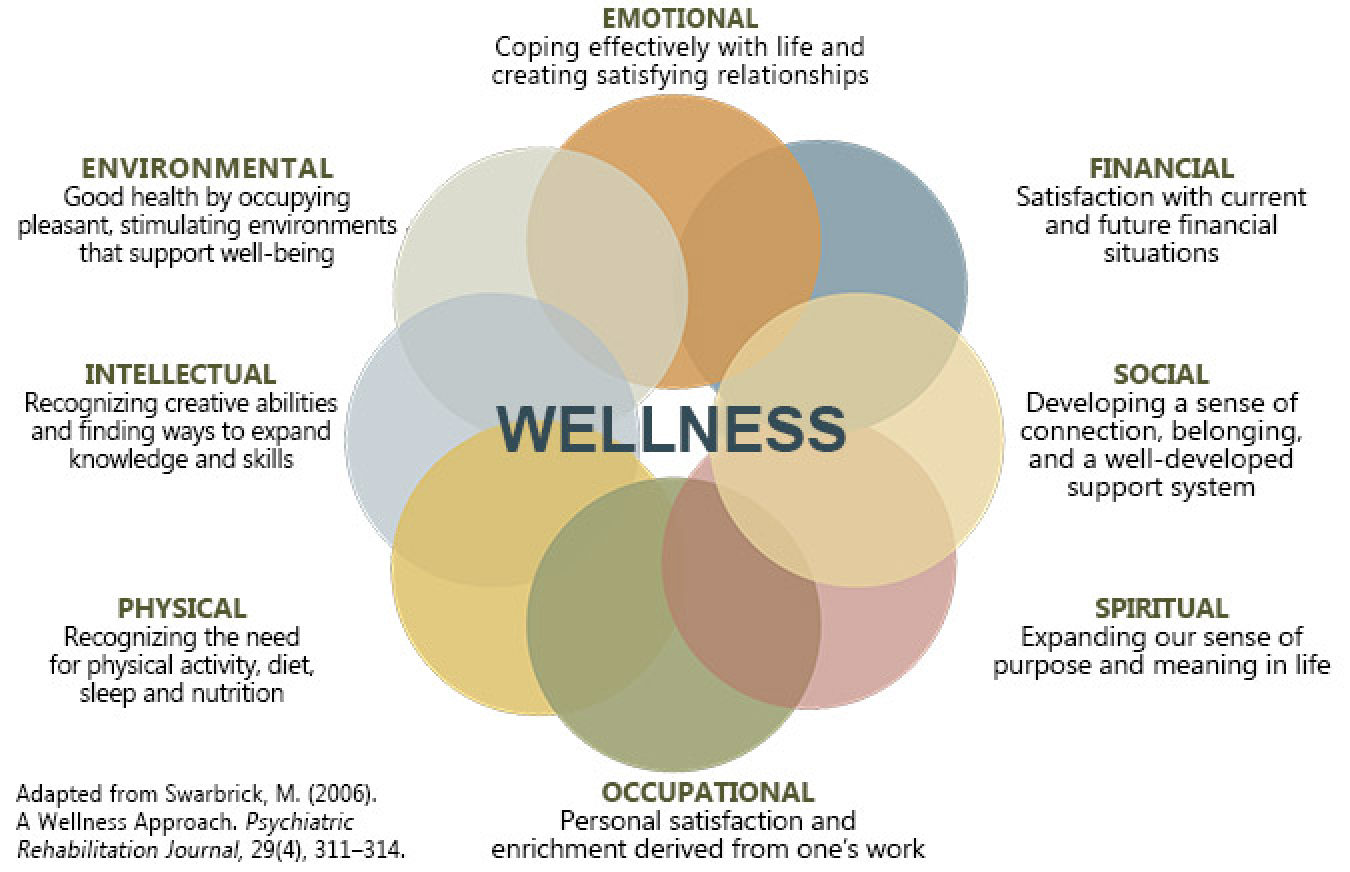

In the 1990s, Dr Peggy Swarbrick, a research professor of psychology at Rutgers University in New Jersey, USA, proposed the “Eight Dimensions of Wellness” model, which encompasses emotional, economic, social, occupational, physical, intellectual, environmental and spiritual well-being.

Where Swarbrick’s model becomes insightful is in the intersections of these dimensions: for example, mental health overlaps with social connectedness (‘sense of belonging’) and professional fulfillment (‘satisfaction with work’).

“Eventually, everything will be gone and my body will no longer be here, so I chose titanium. For me, this is as close to eternity as you can get,” the 68-year-old says.

His Work Transcendence The work, consisting of four 10-metre (33-foot)-tall titanium sculptures suspended from the chapel’s ceiling, is an attempt to transcend the limitations of space and time, and transform conflict into an opportunity for growth and enlightenment, he says.

“My pursuit has always been centered on transcending suffering, difficulty, misery and pain,” Chan reflects, “so that one can reach a state of serenity and peace, which is the essence of my creation.”

This is the only moment you have to create your life, to create something. It’s important to be in the moment and know the value of time.

His determination to impress his boss and keep his job was what propelled him on the path to artistic mastery.

“I had to be good at my work because it gave me my identity,” Chan says, “and the next few years became a search for skills and knowledge and learning how to communicate with my materials.”

After years of immersion and introspection into his craft, he created the Wallace Cut, a dreamlike three-dimensional sculpting technique, in 1987. He says the process transcends mere craftsmanship, it’s a fusion of mind, heart and hand, a state of perfect presence, as if the material itself ceased to exist.

He divides life into an “outer world” and an “inner world,” the outer world being something we observe and are attracted to or repelled from, and the inner world being something we discover when we look within ourselves. Fully accessing the second world takes a lot of practice, but the rewards are great.

“When you look within yourself, your practice begins, you control your desires, you start letting go, and then you find inner strength,” Chan says.

“When I was sculpting, it was like a religious practice – a dialogue with the tools and the raw materials. As a monk, I was able to put into words what I was experiencing,” he says. “Before, I wasn’t able to express it as a spiritual reality.”

Spiritual wellbeing may include religious practice, but a broader sense of purpose, connection and inner peace is important.

“Both religions have brought something to my life, small and big changes, so I’m always torn between the two religions. To me, both churches and temples are sacred places. I go to both churches and temples with respect,” Chan said.

He makes some bold statements about the similarities he sees between the two religions. TranscendenceIn addition to the hanging sculptures, the altar also features two smaller sculptures, one of Jesus and the other of Buddha, although Chan swapped their heads.

“The creative process is a process of constant self-reflection, always searching for purpose, meaning, connection and transcendence. It enhances my spiritual well-being,” Chang said, adding that he hopes the exhibition can provide viewers with a spiritual art experience, “a kind of spiritual upliftment”.

Transcendent experiences free us from ourselves and allow us to connect with something bigger, often giving us a greater sense of purpose and meaning.

While we can take some mental health tips from Chan, the life of an artist isn’t always a fulfilling one: When working on a project, he works long hours and often cuts down on sleep to devote more time to sculpting.

“Transcendence” is on display at the Santa Maria della Pietà Chapel in Venice until September 30th.