The Hindu preacher who recently hosted a “spiritual” gathering of more than 250,000 devotees in north India, where 121 people died when the crowd stampeded, is one of many self-proclaimed messiahs who run various commercially successful cults across the country.

Suraj Pal Singh, a 65-year-old former police officer who transformed himself into a popular “spiritual seer” nicknamed “Bole Baba” – meaning “innocent elder” – in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh about three decades ago and is now in hiding, is wanted for police questioning following a horrific crash in early July in Hathras, 200 km southeast of New Delhi, that killed mostly women and children.

Like other flamboyant “godmen,” Baba claimed to be the reincarnation of various Hindu deities and to have extraordinary powers. Besides using these “talents” to provide financial and spiritual assistance to his poor, mostly low-caste Dalit followers, he also privately claimed the ability to cure various illnesses, disabilities, blindness, and even cancer. At one point, he claimed the ability to bring back to life a 16-year-old girl who had died in a crematorium in Agra, Uttar Pradesh, before police intervention in 1998.

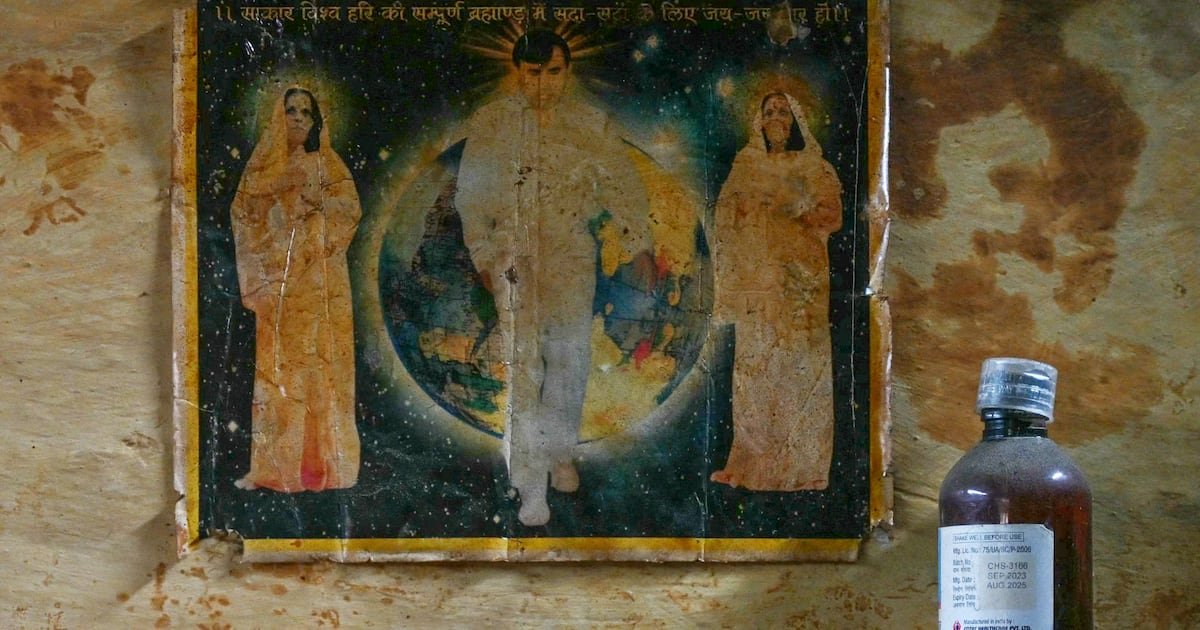

Videos posted on Baba’s YouTube channel, which claims to have more than two million viewers, show Baba arriving to large gatherings of his disciples, such as the one in Hathras, always dressed in a white three-piece suit, in a motorcade of 15 to 20 luxury cars and escorted by a group of uniformed leaders on motorbikes.

An army of volunteers in pale pink uniforms and carrying batons escorted Baba to an elaborate silver throne, and after the welcoming enthusiasm of the assembled (mostly female) crowd had died down, Baba began his speech, promising his devotees a utopian life if they would worship him.

For years, Baba has convinced devotees that the water he pumps from a hand pump at his home near Hathras is “amrit,” or nectar that guarantees long life. Baba also encourages devotees to collect “raj,” or “magic dust,” which rises as he walks or drives past, and eyewitnesses say that frenzied crowds gathering this “offering” sparked a deadly crowd stampede in Hathras.

Police, meanwhile, said Baba was facing charges of fraud, land grabbing and sexual assault. Other deities – known in India as gurus, yogis, sadhus and swamis – are also serving prison terms for a range of offences.

Police also said many such deities, with similar pomp and pageantry, are worshipped unquestioningly by millions of people in India’s complex and ancient fabric of religion, spirituality and multiculturalism, and their collective influence transcends all reason and logic among devotees.

Analysts said the priests’ appeal is directly proportional to their showmanship, their theatrical talents and their ability to make persuasive offers to meet the health, financial and spiritual needs of their followers in turbulent times.

Sociologist Badri Narayan said “miracles” performed by godmen have recently become popular through social media and television channels. He said distressed people flock to godmen in the belief that they can alleviate their afflictions and ailments in exchange for obedient worship of them through touch, amulets and libations.

Political patronage makes these godmen popular, and both parties mutually benefit from their dubious relationship: the politicians benefit from the godmen’s ability to mobilize voters from their vast followings, and in return, they grant the latter immunity from criminal prosecution, land transfers, tax exemptions and other state patronage.

The most recent example of this interdependence is 56-year-old Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh, better known as MSG (Messenger of God), who was sentenced to 20 years in prison in 2017 for raping two girls in the northern state of Haryana and killing a journalist who exposed his deviant behaviour.

But thanks to Singh’s political connections and a cult-like following of more than 60 million people, he has been granted parole nine times since, most recently in January, all ahead of state and parliamentary elections.

For nearly three decades, Singh practiced faith in God and presided over a den of immorality and perversion in his hermitage through violence, intimidation and blackmail. He allegedly ordered the castration of around 400 followers to “bring them closer to God”, but for many years he evaded arrest thanks to political backing from successive state governments that he helped to elect.