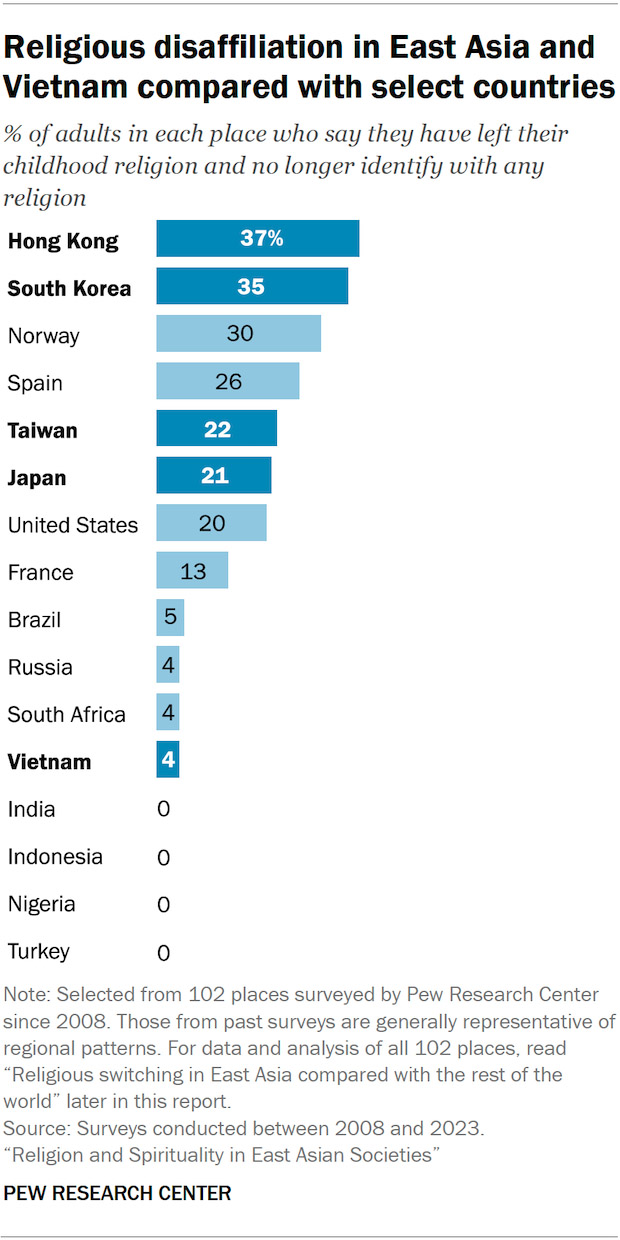

WASHINGTON (RNS) — East Asia has the highest rates of religious abandonment in the world, according to a Pew Research Center study released June 17.

However, many East Asians do not identify as followers of organized religions, but continue to hold spiritual beliefs associated with the faiths of the region.

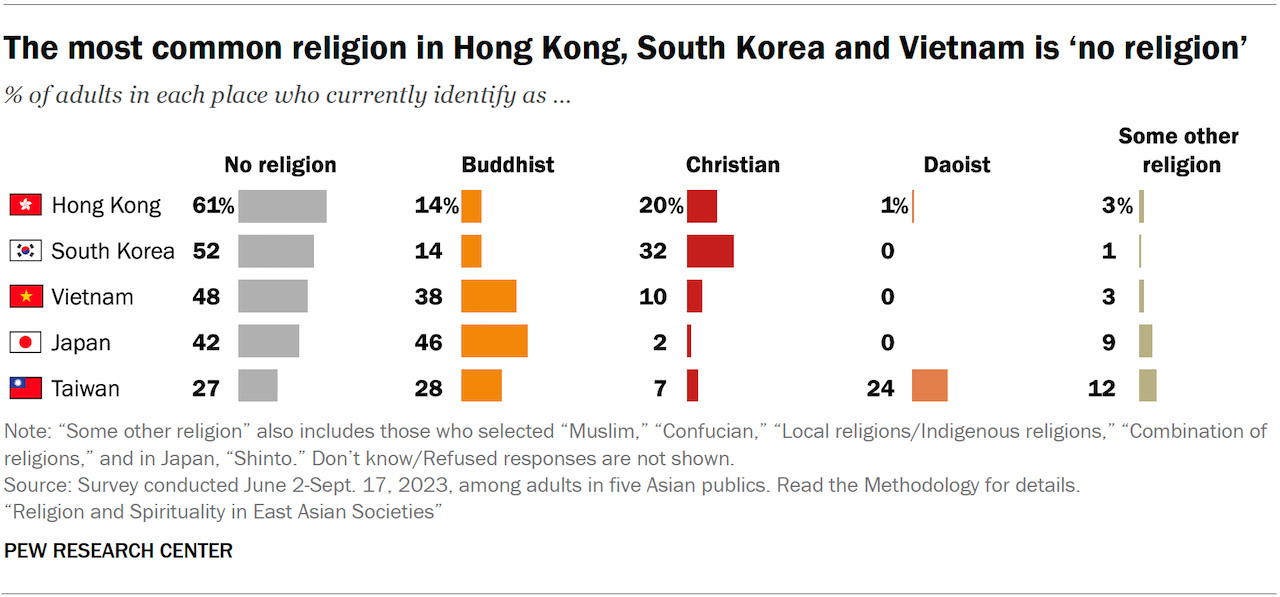

Pew Research Center surveyed more than 10,000 adults over a four-month period in Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and neighboring Vietnam and found that significant numbers of adults across the region say they have no religion, ranging from 27 percent in Taiwan to 61 percent in Hong Kong.

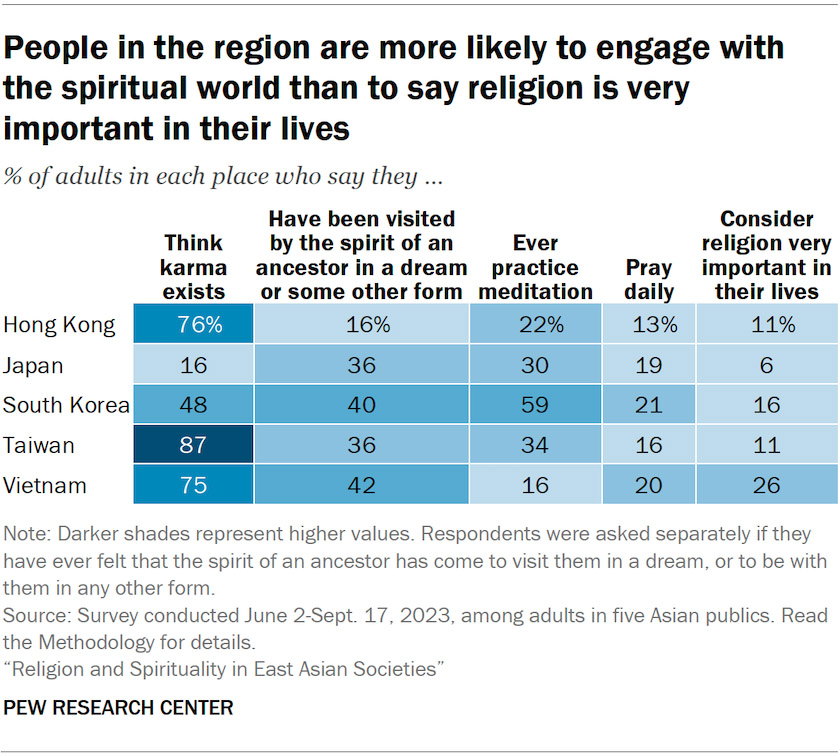

But among those without a religious affiliation, at least four in 10 believe in gods or invisible beings, more than a quarter say mountains, rivers and trees are inhabited by spirits, and more than half make offerings to deceased ancestors.

“When we measure religion in these societies not by whether people say they have a religion but by what they believe and what they do, the region is more religiously active than it might first appear,” the report said.

The survey also points out that the religious identity of people in East Asia is remarkably fluid.

Many say they have transitioned from the religious identity they were raised with to another religion or to no religion: In Hong Kong and South Korea, 53 percent of adults have changed their religious identity since childhood.

The tendency to drop out increases

The trend is to abandon one’s faith rather than change it: Hong Kong (37%) and South Korea (35%) have the highest proportions of adults in the world who grew up religious but now have no religious affiliation, ahead of several Western European countries such as Norway (30%), the Netherlands (29%) and Belgium (28%).

“There’s been a lot of research and discussion about how secularized Western Europe is,” said Jonathan Evans, a senior research fellow at Pew Research Center and lead author of the report, “but there doesn’t seem to be as much discussion about the religious change over the lifetime of people from East Asia.”

Sign up for our weekly edition and get all the headlines in your inbox on Thursdays

He added: “It’s really interesting to see how East Asia and religious identity fit into a more global understanding.”

Despite the high rate of exodus, public attitudes toward proselytizing vary widely: Majorities of adults in Japan (83%) and South Korea (77%) say it is unacceptable to persuade others to convert to your religion.

While opinions on proselytizing are divided in Taiwan and Vietnam, in Hong Kong the majority of respondents (67%) say proselytizing is acceptable.

In Hong Kong, 30% of adults report having no religion growing up, while 61% now report being religiously unaffiliated, a 31-point increase.

Meanwhile, 29% of South Korean Buddhists say they were raised as Buddhists, but only 14% currently identify as Buddhist, a 15-point drop.

The Pew team faced cultural and linguistic challenges in collecting data in East Asia, where the concept of religion is a relatively new concept, introduced by scholars only about a century ago.

Ask the right questions

According to the report, commonly used translations of “religion” are typically understood to refer to “organised, hierarchical forms of religion such as Christianity or new religious movements”, producing results that are “based on Judeo-Christian and Eurocentric ideas”, Evans said.

In the new survey, Pew designed questions to measure common beliefs and practices across Asian societies, revealing a highly vibrant spiritual life among East Asians.

In Taiwan, only 11 percent of adults say religion is very important to them, while 87 percent believe in karma, 34 percent have practiced meditation, and 36 percent have been visited by the spirits of their ancestors.

In another striking example, 92% of non-religious adults in Vietnam say they have made offerings to their ancestors in the past year. Majorities of adults in all five countries surveyed say they believe in unseen beings such as gods, deities or spirits.

Evans explained that while people may subscribe to a particular religious tradition, such as Christianity or Buddhism, the line between ritual and practice is often blurred.

“Some might classify this as a Buddhist practice, but do you see Christians doing this? Do you see non-religious people doing this?” he asked.

“People may label themselves, but that doesn’t necessarily reflect what beliefs or practices they hold.”