As a graduate student, I served as a teaching assistant in what I perceived as and experienced as a transformative course. The psychology of the African American experience. This was a course unlike any I had studied before. It was a learning space entirely focused on understanding the psychological nuances of Black life from a Black scholar’s perspective. I remember every time I walked into that course, there was an energy of constant curiosity and desire to learn more among the students. As the course progressed, I witnessed the students, especially the Black students, transform as they learned about themselves and their communities through the lens of Black psychology, a lens that not only centers the Black experience but also identifies history as the foundation for how one shows up and moves in the world. It was humbling to witness and experience the deep pride, determination, collective sadness and elation, critical consciousness, frustration, and connection that emerged from discussions of who Black people are and have been in this world.

Years later, in a meeting with a colleague, he asked, “What does history have to do with Black psychology?” From my experience as a teaching assistant, I remember being a bit surprised by the question. In that moment, I also realized that the question reflected a particular orientation to the study of psychology, one that might acknowledge the presence of cultural and historical context, but that does not consider history and tradition to be central to Black mental health and well-being. Now, as I myself teach a course that focuses on the connections between Black history and psychology, I am frequently reminded of how important it is to be part of conversations that help reorient the psychology of the Black experience to center history and tradition.

Historical background and psychology

The notion of historical context being peripheral to psychology is by no means new. There has long been tension about how, or to what extent, historical context and narratives are taken into account to understand the psychology of Black people, or racially and ethnically marginalized groups more generally. One need only consider the fact that topics such as culture, race, and even historical considerations were not part of social science research or theory until the second half of the 20th century to understand the unique relationship between psychology and history. Culture and its associated historical narratives were viewed as subtle and irrelevant in light of theories premised on universal human experiences.

But how can human experience be universal if the experience of human history is not universal? Afrocentric, Professor and philosopher Molefi Kete Asante reminds us that “the true character of a people lies in how it relates its history to its present and future.” While many human experiences can certainly be thought of as universal (for example, people desire connection and experience emotions), the ways in which people make meaning of their experiences, live their present, and envision their future are deeply defined by and connected to their history and heritage. This is especially true for black people.

The Importance of Black History

Black psychologists and scholars working on multiculturalism and social justice in psychology have a long history of A complete and accurate historyprovides fertile ground for mental health rooted in black humanity, resourcefulness and resilience. In fact, black psychologists like the late Asa G. Hilliard III have affirmed that it has a history stretching back to ancient Africa and has been a compass for black educational, spiritual and social freedom.

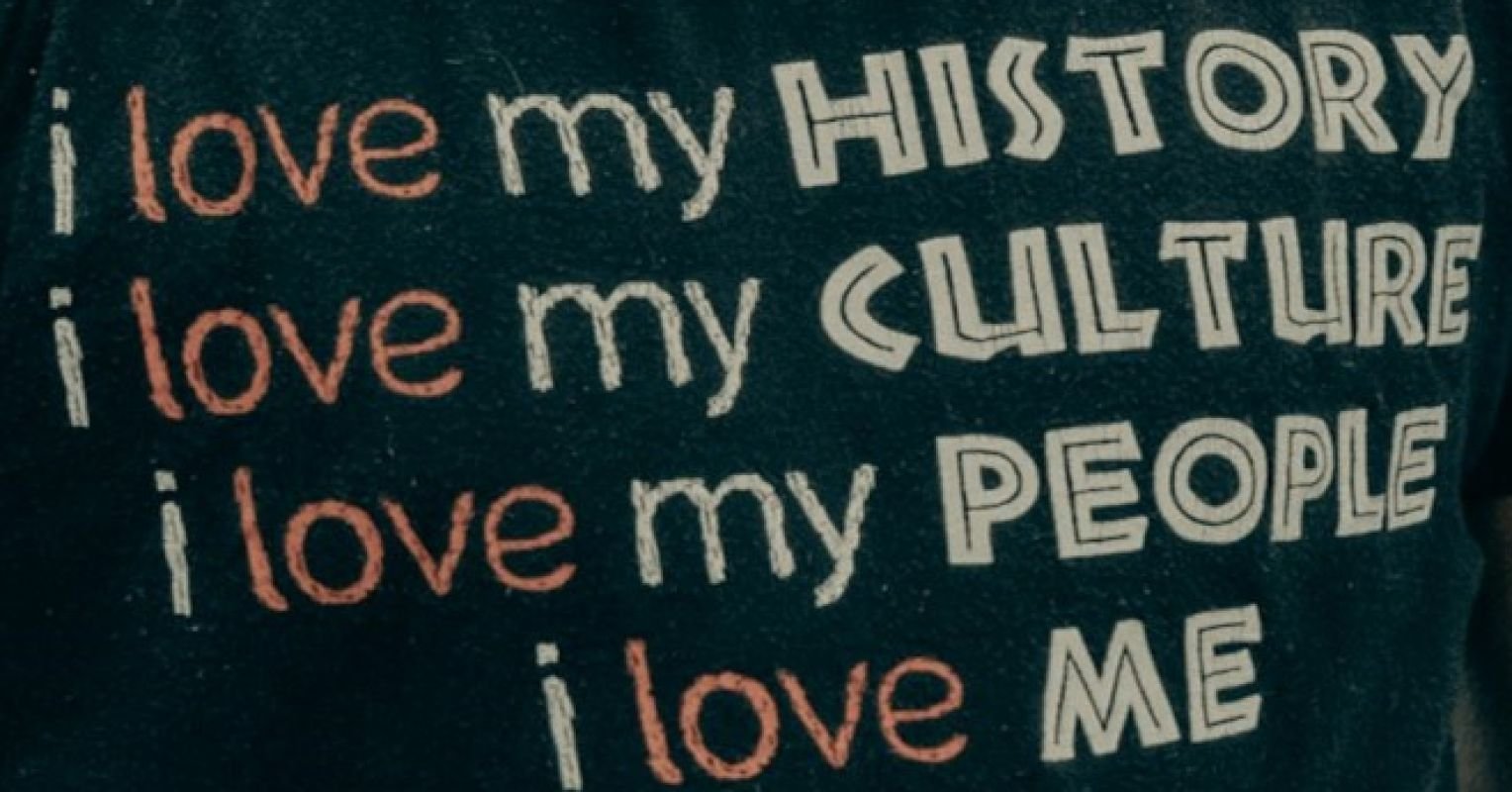

Hilliard’s position on the importance of history to Black people is substantiated by research showing the link between Black history and psychological outcomes. For example, Adams-Bass (2014) found that Black youth who are knowledgeable about Black history are less likely to endorse stereotypical and derogatory media images of Black people. This research also shows that exposure to Black history has a positive impact on racial identity development (Chapman-Hilliard and Beasley, 2018). In other words, Black history has been demonstrated to shape how Black people interpret the world around them and influence how they think about the self and the group.

Further pointing out the importance of history to Black health, Maulana Karenga writes: “History is the essence and mirror of a people’s humanity, not only in the eyes of others but also in their own eyes. It reflects…not only what they have done but who they are, what they can do, and just as importantly, what they can become as a result of a past that reveals their potential.” If I were to respond to my colleague now about how history relates to Black psychology, I think I would share that Black history around the world creates infinite possibilities for psychological health. Some may see the resistance, joy, hope, and prosperity found in Black communities as a collection of individual stories and narratives that never intersect. But Black history teaches us that these stories reflect the interconnected potential of so many people who have forged a path when sometimes there seemed to be no path.

History is made every day, and when Black people connect with possibility through knowledge of history and the undeniable courage of their ancestors, the experience of health, healing, and wholeness has no limits, only possibilities.