Anyone who meets Deborah Epstein, the architect and artist behind such projects as Rockport’s Waterfront Music Hall, would likely see her as a successful professional.

Epstein, founding principal of Epstein, Joslin & Picardi Architects, has been haunted by the memory of a knife attack on the Columbia University campus in 1977, when he was a student at Barnard College.

She endured the legal quagmire that followed after her assailant was indicted, and eventually pleaded guilty to the least amount of charges. But the memories of the stalking and threats never went away. Now, nearly 50 years later, she’s using the power of art to reclaim the parts of herself that the experience left buried.

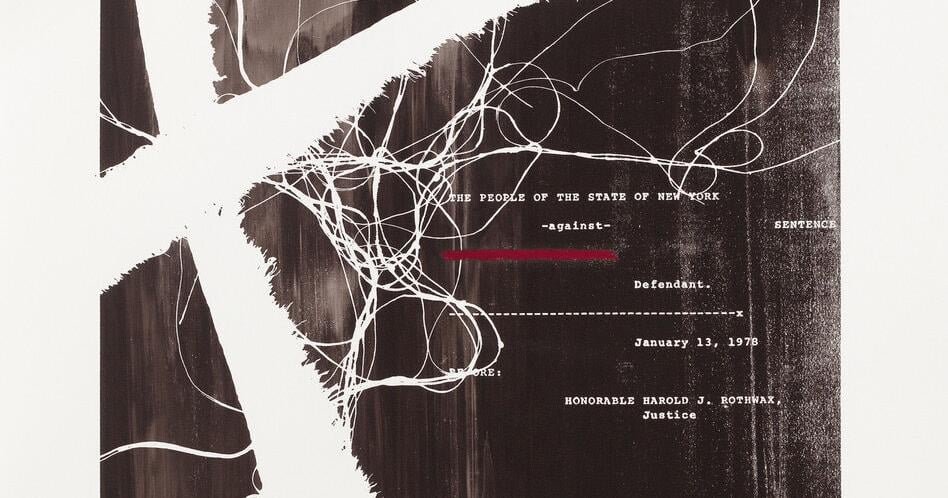

Epstein’s new exhibition, “No Words: Meditations on Being Stalked and Stabbed,” features 11 prints and has opened at the Mercury Gallery in Lockport. An artist talk will be held on Saturday, June 22, at 3:30 p.m.

The fingerprints emerged after years of poring over the “monster file” of documents relating to the incident in which she was stabbed in the head about two weeks after her ex-fiance threatened her with a knife.

“When I was 21, an ex-boyfriend tried to kill me. All I leave from that moment, over 45 years ago, are three scars on my scalp, a two-inch file of my father’s phone notes, court papers, and correspondence, and anger and a deep distrust for the system that was supposed to protect me. I called the work ‘No Words’ in part because those two-inch files are filled with so many words — my father’s words, my school’s words, my lawyers’ words, the courts’ words — but none of them are my words,” Epstein writes in her artist statement.

After graduating from college, Epstein earned a master’s degree in architecture from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, then got married and started a family.

It wasn’t until 2017, when her father’s aging became noticeable, that she asked him to see his files. She knew they must exist: He had files on each of his four children and six grandchildren, chock-full of paperwork about their childhoods and adolescence. In this case, she wanted to see her own case file; the story about the assault was a front-headline story in the college newspaper, the Columbia Daily Spectator.

“My father was a lawyer and controlled all communication and decision-making to ensure I was well taken care of,” Epstein recalled.

But the psychological and emotional wounds remained.

“When I started reading the files, I knew I needed to do something with this material, but I didn’t know what,” she said.

Gallery director Amnon Goldman was quick to support and encourage Epstein’s new work.

Epstein, a weaver and textile artist, initially thought she could create a textile project or even a series of quilts using the original documents.

“I ended up deciding to work thematically instead of chronologically, and I turned to printmaking because it allowed me to manipulate handwritten notes, typewritten letters, and court documents,” she said. “I could highlight important phrases or bring together parts of different documents to express emotion. Another reason printmaking made sense to me was that when I dropped out of college due to safety concerns, I took a printmaking class at the University of Michigan Art School. That class helped me find peace of mind and help me thrive during these difficult times. So it made sense to return to printmaking for this project.”

As she pored over hundreds of documents, she realized she didn’t want to emphasize words like district attorney and lawyer.

“I used parts that added more depth to my story,” she said.

Epstein recalled how terrified she felt when her ex-fiance violated his bail conditions and stalked her relatives.

“I was constantly scared and felt like I was drowning,” she said, referring to a piece in the exhibit called “Fear.”

The titles of the works in this series include words like “Forgiveness” and “No Consequences,” giving the viewer a sense of what experiences are explored in the prints.

“This story is mine, but unfortunately its themes will be all too familiar to so many, especially women,” Epstein said. “An unexpected outcome of this exhibition is that it has encouraged story-sharing. Resilience is the goal.”

Throughout the process, the exposure of her work has elicited many uncomfortable personal stories from viewers.

Sharing an anecdote about some kind of twist of fate, shortly after the raid, Epstein asked Barnard College what measures would be taken to ensure her safety, to which one administrator joked, “What should we do, get a bodyguard?”

But when Joan Mondale was to be the commencement keynote speaker, Barnard gave her a bodyguard, Epstein recalled, presumably because they didn’t want an incident to mar the celebration.