Highlights:

- Women with breast cancer undergoing endocrine therapy experienced fewer hot flashes and less symptoms after receiving early acupuncture treatment.

- Immediate acupuncture also improved quality of life scores.

Acupuncture significantly reduced hot flashes and improved quality of life in women receiving endocrine therapy for breast cancer, according to three parallel randomized trials. cancer.

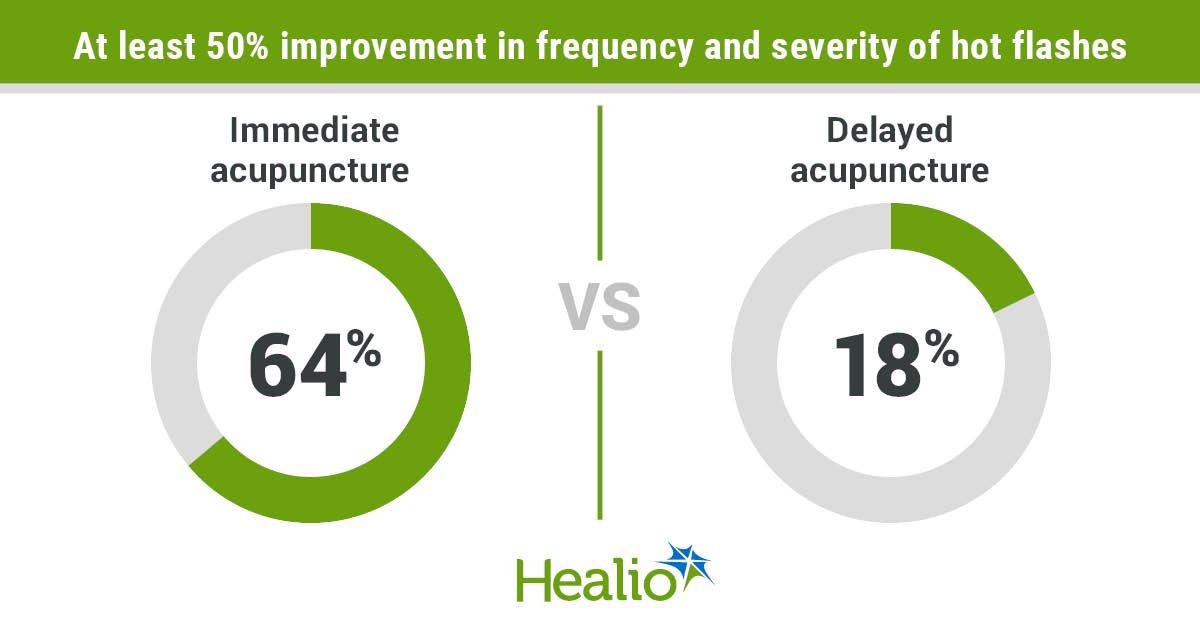

Hot flash scores, calculated by measuring the frequency and severity of patients’ hot flashes, were reduced by more than 50% in 64% of women who received immediate acupuncture at the start of endocrine therapy, compared with 18% in the control group who received delayed acupuncture.

Lu Weidong

“Unlike many medications that only target a single symptom, acupuncture has been proven to treat multiple symptoms simultaneously.” Weidong Lu, MB, MPH, PhD, “We’ve seen improvement not only in hot flashes, but also in a range of hormonal symptoms and overall quality of life. This holistic approach is especially helpful in managing the complex side effect profile of endocrine therapy,” the oncology acupuncturist in charge of the Leonard P. Zakim Center for Integrative Therapy and Healthy Living at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute told Healio.

Background and methodology

According to background information provided by the researchers, approximately 2.3 million new cases of breast cancer are diagnosed each year worldwide, and 685,000 women die from the disease.

Endocrine therapy can reduce the risk of recurrence or death in women with hormone receptor positive breast cancer, but it can also have side effects.

Approximately 80% of patients undergoing endocrine therapy experience hot flashes, which can affect mood and quality of life and may lead to discontinuation of treatment or medication.

“The dilemma is balancing the need for long-term use of the drugs, usually for five years or more, with managing these debilitating side effects,” Lu said.

“There are several pharmaceutical options to alleviate these effects, but they often come with side effects,” he added. “This is where acupuncture comes in as a promising non-pharmacological approach.”

Previous studies have evaluated acupuncture as a potential treatment for hot flashes, with mixed results.

Lu and his colleagues aimed to find more consistent results through a multinational study that included three trials with the same eligibility criteria and treatment protocols, one each from the United States, China, and South Korea.

The trial, which ran from January 2019 to February 2022, included women with stage 0 to stage III hormone receptor-positive breast cancer who had completed chemotherapy or radiotherapy, received at least four weeks of endocrine therapy, and experienced at least 14 hot flashes per week for four weeks.

The immediate acupuncture group received acupuncture twice a week for 10 weeks followed by 10 weeks of observation. The delayed acupuncture control group received no acupuncture for the first 10 weeks, but then received acupuncture once a week for the next 10 weeks.

The researchers randomly assigned 158 women (median age 48 years; 52.5% Asian, 39.9% Caucasian) to immediate acupuncture (n = 81) or delayed acupuncture (n = 77) groups.

The US trial involved 78 participants, while South Korea and China had 40 participants each.

Study participants experienced an average of 6.3 hot flashes per day at baseline.

The researchers assessed the Endocrine Symptom Subscale (ESS) score as the study’s primary endpoint and the weekly change in hot flash score as a secondary endpoint.

Results and next steps

Women who received immediate acupuncture had significantly improved ESS scores at week 10 compared with women who received delayed acupuncture (P = .0003).

Of the 136 participants who completed the 10th week of the study, 55 achieved clinically significant improvement (54% of the study group, 26% of the control group). P = .0009).

The largest improvement was seen in South Korea (change in ESS score: +8.5), followed by the United States (+5.3) and China (+1.7). This result surprised the researchers.

“The differences in symptom profiles observed between Chinese and Korean patients highlight the importance of taking individual and cultural factors into account in treatment planning,” Lu said.

The researchers observed a significant difference in hot flash scores at week 5.

Women in the immediate acupuncture group also had significantly improved quality of life scores compared with women in the control group.

Participants in the delayed cohort who received acupuncture experienced significant improvements in ESS and hot flash scores from the 10th week of treatment onwards.

Lu et al. reported no serious adverse events related to the intervention.

The researchers noted limitations in the study, including the use of a delayed acupuncture control rather than a pragmatic control, which increases the possibility of a “placebo effect”, a lack of diversity in the cohort, and differences in needle size and choice of equipment as the trial was conducted across multiple locations.

Lu said future studies could address multiple questions, such as whether acupuncture affects adherence to endocrine therapy, how acupuncture affects different racial and ethnic groups, and the underlying mechanisms that make acupuncture effective.

“Acupuncture should be seen as a complement to traditional cancer treatments, not a replacement,” says Lu, “It enhances the overall treatment package to improve patients’ health and treatment outcomes. As evidence accumulates, we need to consider how to effectively integrate acupuncture into standard oncology care pathways to ensure all appropriate patients have access to this beneficial treatment.”

For more information:

Weidong Lu, MB, MPH, PhD, Please contact us at weidong_lu@dfci.harvard.edu.