Professor Stuart Cook, from the Medical Research Council Institute of Medical Sciences at Imperial College, said: “The findings are extremely exciting.

“The treated mice had less cancer and didn’t show the typical signs of aging and frailty, but they also saw less muscle wasting and better muscle strength. In other words, the anti-IL11[treated]old mice were healthier.”

“Although these findings were only obtained in mice, they raise the intriguing possibility that this drug may have a similar effect in elderly humans.”

Humans inherited the interleukin-11 gene from fish hundreds of millions of years ago.

But while this adaptation was useful at the time, and still helps some species regenerate limbs today, it is now thought to be largely unnecessary in humans, causing tissue thickening, scarring and inflammation that contribute to ageing and disease.

The researchers came up with the idea that silencing IL-11 might be linked to aging after they noticed that the protein increased dramatically with age in lab animals.

‘Very excited’

“Out of curiosity we ran some experiments to look at IL-11 levels and we were really excited to see that the levels of IL-11 clearly increased with age,” said Anissa Wijaya, an associate professor at Duke National University of Singapore’s School of Medicine, who is collaborating with Imperial.

“We found that these elevated levels contribute to adverse effects in the body, such as inflammation and the inhibition of organ healing and regeneration after injury.”

The team had already found that this protein causes inflammation and prevents tissues from regenerating properly, so they wanted to see if blocking it could slow the ageing process.

Initial experiments with gene-edited mice in which the gene that produces IL-11 was deleted showed that the simple gene deletion extended the mice’s lifespan by an average of more than 20%.

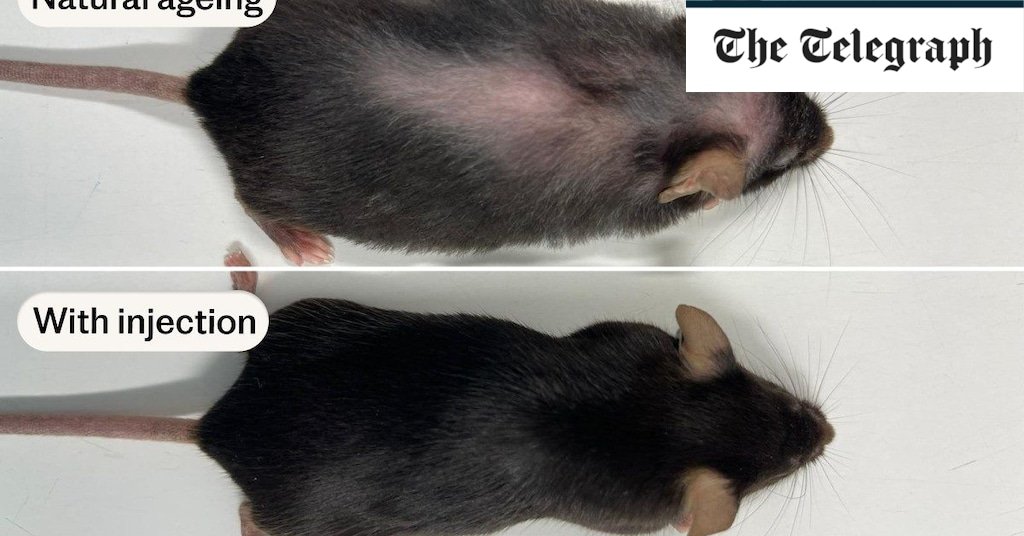

The scientists then treated 75-week-old mice (equivalent to about 55 human years) with injections of anti-IL-11 antibodies that block the effects of IL-11 in the body.

The researchers described the results as “dramatic”: Mice’s lifespan was extended by up to 25 percent, and the treatment significantly reduced cancer mortality in the animals, as well as preventing fibrosis, chronic inflammation and metabolic disorders.

“Your lungs will improve”

Professor Cook added: “The mice had stronger muscles, better lungs, better skin, better hearing, better eyesight and all sorts of improvements.”

“This means that it’s possible not only to delete the gene from birth, but also to administer a therapeutic drug later, opening up the possibility of applying this to humans.”

“Our goal is that one day anti-IL11 therapies will be available as widely as possible, helping people around the world live longer, healthier lives.”

Three companies are currently conducting clinical trials of anti-IL-11 therapeutics for scarring lung disease, fibrotic eye disease, and cancer.

Lassen Therapeutics, the company running the US trial, says the drug has an “excellent safety profile” and experts say it should be relatively easy to launch clinical trials in ageing.

Dr Wijaya added: “Although our studies were carried out in mice, studies in human cells and tissues have confirmed similar effects, so we are hopeful that these findings will be highly relevant to human health.”

“This study is an important step towards a deeper understanding of aging, and we have demonstrated in mice a treatment that has the potential to extend healthy aging by reducing frailty and the physiological signs of aging.”

The study was published in the journal Nature and was partly funded by the Medical Research Council.