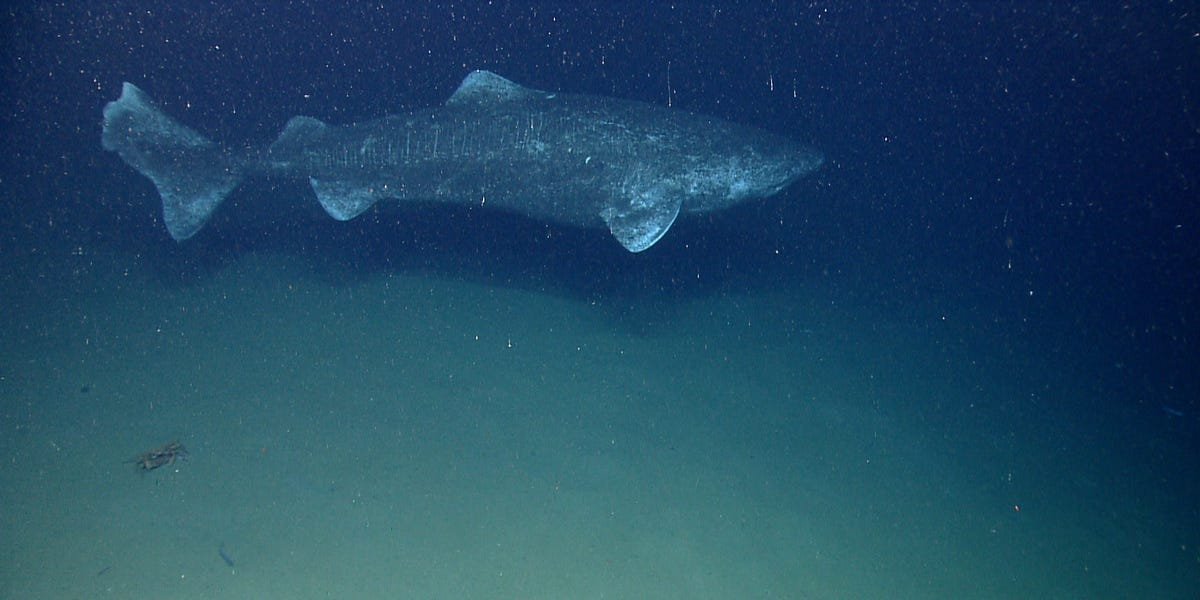

- Greenland sharks can live up to 400 years, making them the longest-living fish.

- Researchers are working to unlock the secrets of these sharks’ longevity.

- Understanding the lifespan of Greenland sharks could improve research into human health and ageing.

Abigail Adams, wife of the second President of the United States, was born in 1744. It is quite possible that the Greenland sharks that swam in the North Atlantic at that time are still alive today.

There’s no doubt that these large, carnivorous sharks can live for hundreds of years: in 2016, researchers found that they can live for at least 272 years, but could potentially live up to 400 years.

However, just why this shark is able to live such a long time remains a mystery – it’s thought that this may be due to the shark’s slow growth rate and low metabolic rate, but research is still ongoing.

Scientists hope that by unlocking the secrets of how these fish age, humans can help live longer, healthier lives. While we’ll probably never live to be 400 years old, extending our average lifespan by even a decade would be a breakthrough.

One of the scientists working on the study is Euan Camplison, who studies shark metabolism for clues about the ageing process.

“Better understanding of the anatomy and adaptations of long-lived species like the Greenland shark may help improve human health,” Camplison, a PhD student at the University of Manchester, told Business Insider.

A lifelong slow metabolism

According to National Geographic, Greenland sharks are lazy swimming fish that live mainly in the Arctic and North Atlantic Oceans and can grow to between 8 and 23 feet in length and weigh up to 1.5 tons.

These predators eat salmon, eels, seals, and even polar bears when the opportunity arises. But they also likely go long periods between meals. A 2022 study found that the 493-pound fish could easily survive on just 2 to 6 ounces of food a day.

Camplisson’s new research, presented earlier this month at the Society for Experimental Biology annual meeting, suggests that sharks’ metabolic rates may not decline as they age, which could help explain why they live so long.

The same isn’t true for most animals, including humans: our metabolisms tend to slow down as we age, for example, which can lead to unhealthy weight gain.

Camplison looked at the activity of five metabolic enzymes in preserved greyhound muscle tissue, and said, “In most species, we would expect the activity of these enzymes to change as the animal ages.”

“Some of them will decline over time as they begin to malfunction or deteriorate, but others will compensate and increase activity to keep the animal producing enough energy,” he added.

The Greenland sharks he studied, estimated to be between 60 and 200 years old, showed no significant change in enzyme activity, although of course the same may not be true for the third or fourth century, since a Greenland shark may be middle-aged at 200 years old.

Camplison plans to examine more enzymes to see if and how they change as sharks age.

Aging is complex

There’s still a lot of work to be done before this kind of research can be applied to humans.

“Aging is an incredibly complex system, and we still don’t have clear answers to how it works,” Camplison said.

For example, metabolic changes are only a small part of human aging — genetic errors, protein instability, and several other processes are known as “hallmarks of aging,” and Camplison believes sharks have a lot to teach us in these areas.

“We want to take a closer look at some of these characteristics and see whether the Greenland sharks are showing traditional signs of ageing,” he said.

The Greenland shark’s incredible aging process has allowed it to survive for centuries, but it can be a double-edged sword as its environment changes rapidly.

Camplison said the species, listed as “near threatened” by the World Conservation Union, may be too slow to adapt to climate change, marine pollution and other stressors.