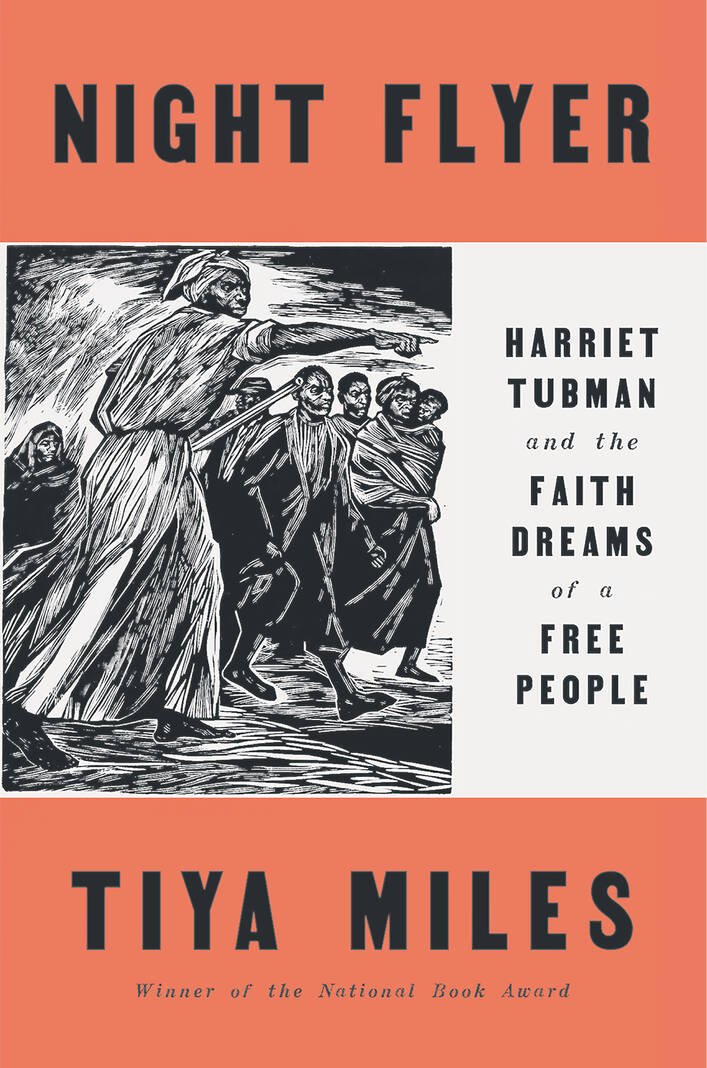

“Nightflyers” by Tiya Miles

Penguin/TNS

The subject of scholarly books, graphic novels and Hollywood movies, Harriet Tubman is widely known by elementary school children as well as viewers of public television documentaries, and her image will likely be etched in the wallets of millions of Americans in coming years as her portrait replaces Andrew Jackson’s on the $20 bill.

What else can be said about such a well-known historical figure? A lot, in fact.

In her insightful “biography of faith,” Night Flyer: Harriet Tubman and the Faith Dream of a Free People, Tiya Miles focuses on a lesser known aspect of Tubman’s life: the intertwined relationships with God and nature that underpinned her unwavering moral beliefs and connected her to other faithful black women of the 19th century.

In the decade since she escaped slavery in 1849, Tubman conducted numerous harrowing rescues and freed 70 slaves. Her heroism continued in the Civil War, when during fighting in South Carolina, Tubman helped free hundreds of slaves.

“Throughout her life, Harriet relied first and foremost on God,” writes Miles, a National Book Award winner (All That She Carried) who earned a doctorate in American studies from the University of Minnesota.

Miles places Tubman in an important lineage of black faith figures. Like Tubman, Jarena Lee, Zilpha Erow, Julia A. J. Foote, and a writer known as Old Elizabeth, wrote or dictated their spiritual lives in the decades before and after the Civil War. These black women, Miles writes, “took radical steps to preach and act on what they believed to be the word of God.”

As Miles describes it, Tubman’s faith went through several stages. As a child, she prayed “for a fighting chance in this unjust situation.” After a slave owner threw a heavy object at a slave boy, hitting Tubman in the head, “she may have come to a new state of spiritual being,” Miles writes, and her faith grew. She prayed to God to kill the man who had enslaved her. When the man died, she felt remorse, and “this only strengthened her faith.”

Miles draws many parallels between Tubman and the other women. All suffered physical illnesses and injuries at a young age, and each viewed these hardships through a spiritual lens, Miles writes. Similarly, Tubman was one of the black spiritual women of her time who “appealed to God beneath the trees, in the fields, and among the livestock she deemed sentient.”

Tubman told her biographer that in her dreams she was flying like a bird over the fields. Ello and Old Elizabeth used similar imagery to describe themselves. But while their birds were “speckled, or dark in color,” representing gender and race, Tubman’s bird was white, and it seemed to soar “beyond geographical reality” and “unconstrained by society’s rules,” Miles writes.

There are always gaps in Tubman biographies. For Miles, this is not an obstacle: Tubman bought a bull, but “we can only imagine whether she whispered to the bull or stroked its broad flanks before or after work,” Miles writes.

This book, more than many others, finds beauty in history’s unanswered questions.