Nutrition policy in Madagascar

A review of nutrition policies and programs carried out since independence highlights Madagascar’s institutional approach to combating malnutrition, which has evolved over time and has become increasingly relevant to national development policies.

The establishment of the nutrition policy follows Madagascar’s participation in various international conferences on nutrition and compliance with the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Therefore, the first National Nutrition Policy (NNP) was implemented in 2004. Its general goal was to halve the prevalence of chronic malnutrition in children under 5 years of age.

Several programs and projects have been established to implement nutrition policies. From 1985 to 1989, the Project on Strengthening Legislation and Action on Nutrition (1985-1989) and the Project on Strengthening Food Management Structures (1989-1992) were carried out. In 1989, the country developed the Food and Nutrition Surveillance Program, followed by the National Program to Combat Nutrient Deficiency (1990-1994).

Since 2006, Mother and Child Health Week (MCHW) has been implemented to ensure vitamin A supplementation and deworming for children under five years of age and pregnant women. This campaign is held across the country twice a year by offering free intervention packages. Additionally, routine immunization reinforcement sessions are being organized to improve immunization coverage among children and pregnant women.footnote 2.

Rice production status in Madagascar

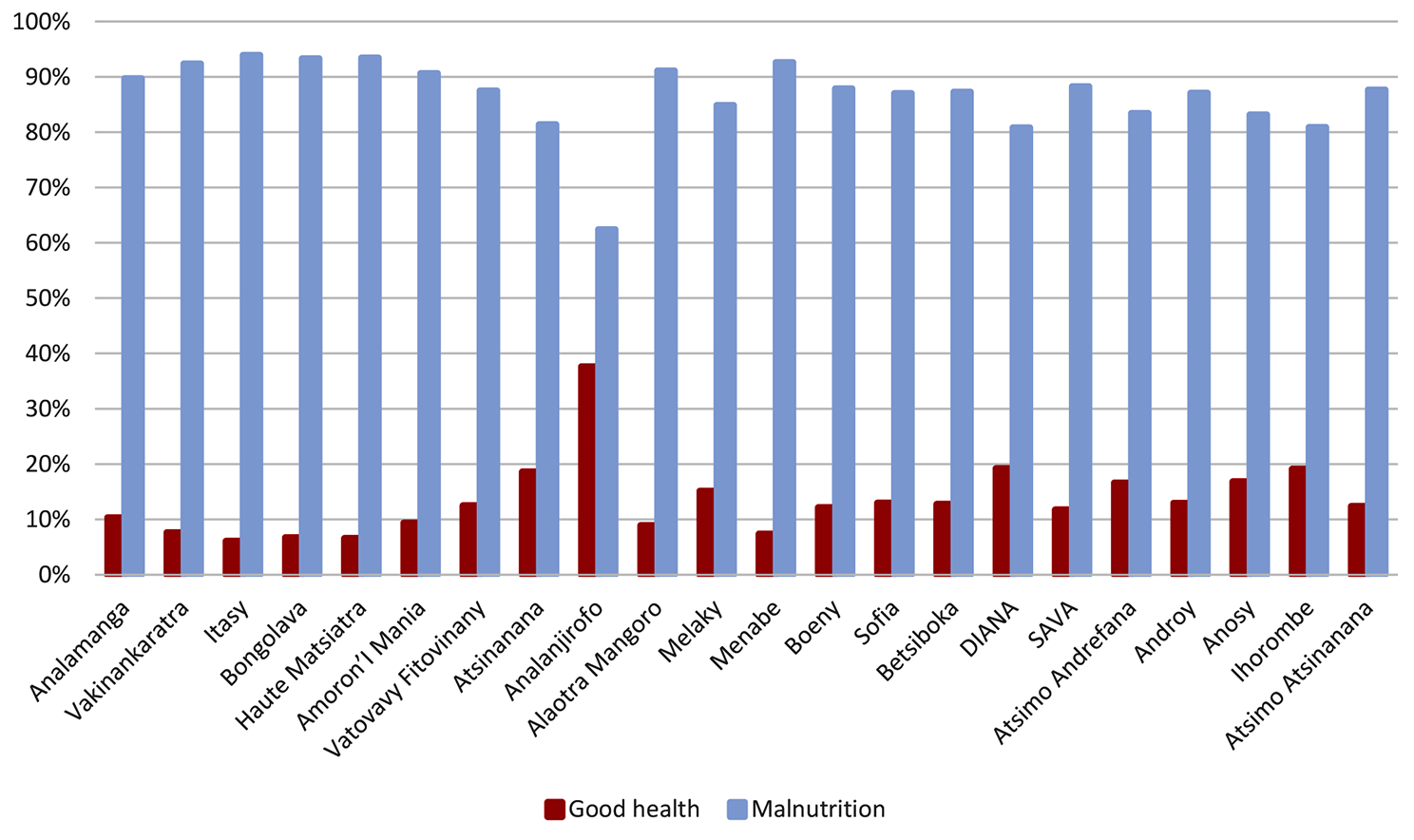

The relationship between rice production and nutrition is not yet clear. Of Madagascar’s 22 regions, the central highlands, comprising Vakinankaratra, Itasi, Alaotra-Mangolo, Amoroni-Mania and Analamanga, are the most affected by malnutrition. Nevertheless, these areas are Madagascar’s rice breadbasket, producing an average of 500,000 tons per year. Production in the region in 2018 was 540,000 tonnes (World Food Program Data, 2019).

Most Malagasy households consume rice as a staple food three times a day. The average annual consumption of rice per person is 130 kg. [11], rice production is still lower than consumption. This situation is due to the underdevelopment of arable land (only 10% of the 36 million hectares of arable land is cultivated), the insufficient level of development of hydroponic agricultural infrastructure, the use of rudimentary methods and the level of This is explained by several factors, including the low Development of road infrastructure limits access to food products. To avoid malnutrition and stabilize rice prices due to insufficient supply compared to demand, the Malagasy government had to import rice. The main suppliers are India, Pakistan and Thailand. [12]. The price of imported rice is lower than the local rice price, at 1,900 MGA, compared to about 2,300 MGA in December 2020 (Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries data, 2021). Therefore, this price stabilization policy should also contribute to the fight against malnutrition in Madagascar.

Impact of nutrition and agricultural policies on nutrition outcomes

According to Luo et al. (2020), “malnutrition in all its forms” can be measured using indicators based on the six global goals endorsed by the World Health Assembly and can indicate nutritional outcomes. [13]. Indicators include stunting, wasting, overweight in preschool children, anemia in women of childbearing age, low birth weight, and exclusive breastfeeding. Among micronutrient deficiencies, vitamin A deficiency is a major concern, especially for children living in developing countries.According to UNICEF, about a third of children don’t get the amount of vitamin A they need [14].Children who were not fed foods rich in vitamin A were more likely to be anemic. [15].

Kangas et al. (2020) studied the impact of a therapeutic feeding program on children with acute malnutrition. [16]. Treatment consisted of providing sufficient micronutrients and was aimed at restoring the body’s reserves. However, treatment has had little success. In other words, there was no difference in vitamin A status before and after treatment. [16]. Therefore, the authors suggested reviewing therapeutic nutrients. However, Bhutta et al. (2013) showed that vitamin A supplementation reduced all-cause mortality by 24% and diarrhea-related mortality by 28%. [17].Reinforcing this point, Keats et al. (2021) report that multiple micronutrient supplementation is highly beneficial for health. [3].

Parasitic infections also cause anemia, limiting a child’s physical and cognitive development. [18]. Sudarsanam and Thariyan (2013) studied the effects of deworming on infected children. The results showed that deworming increased the children’s weight and ultimately their hemoglobin. [18].

Next, Ecker & Qaim (2011) studied the effects of income and price policies on nutrient consumption and the prevalence of nutritional deficiencies. The authors found that income-related policies are better suited than price-related policies to improve nutrition. [19]. Pandey et al. (2016) analyzed the impact of agricultural interventions on nutritional status in South Asia. The results showed that targeted production of nutritious crops and diversification of agricultural production can improve nutrient intakes and nutritional outcomes. [20].

Regarding the relationship between food prices and nutrition, many studies, generally based on household surveys, have shown a strong association between these variables. Recent research on Indonesia’s rice market and policy suggests that some liberalization, rather than raising domestic prices and stimulating production, could help the government achieve its nutrition goals. [21, 22]. Ecker & Qaim (2011) argued that price shocks for major staple foods have a significant impact on dietary habits, particularly for food buyers in rural areas. [19]. Henriques et al. (2013) found in a study of eight developing countries that high simulated food prices reduced average consumption and food intake and worsened the calorie distribution of food. [23].

Other determinants of malnutrition

Regarding other determinants of malnutrition, child characteristics can explain malnutrition, such as the child’s health status. Akira Tano (2010) Fever and diarrhea are associated with chronic malnutrition. In fact, the disease causes loss of nutrient intake and disturbances in metabolism. [24].

Malnutrition can also depend on the child’s gender. In their studies, Kobelembi (2004), Mukalay et al. (2010), Black et al. (2013) and Augsburg & Rodriguez-Lesmes (2018) found that male children were more likely to be malnourished. [17, 25,26,27].Additionally, many studies show that the risk of stunting increases with age. [26].

Regarding maternal variables, body mass index (BMI) [17, 24]education level [28] and age [25] Associated with stunting in children. Breastfeeding is one of the factors determining a child’s nutritional status. You can receive all the nutrients necessary for growth up to 6 months of age.But its importance transcends this era [24, 29].

Other household characteristics, such as hygiene, use of “safe” toilets, etc. [29]access to safe water [26] and access to health care [30], which can also explain chronic malnutrition in children. Finally, disparities in activities and lifestyles between urban and rural areas lead to unequal risks of exposure to malnutrition. Urban areas have a well-developed medical infrastructure and are characterized by a greater number of medical professionals than rural areas. For Waiheniya et al. (1996) and Fagbamigbe et al. (2020), rural areas are more prone to malnutrition than urban areas. [31, 32].

In summary, Harris & Nisbett (2020) described the basic determinants of nutrition. The authors identified three interrelated factors: First, it is a resource that indicates the potential for individuals or groups to benefit from a good or service, such as purchasing food or accessing appropriate health care. Second, the social structures that condition access to these nutrition-related goods and services. Third, social patterns (gender, ethnicity, religion, age, disability) create inequalities for some groups. [33].