In 1990, as the Soviet Union was moving toward its final collapse, a famous Russian writer sketched out plans for a post-Soviet future. As the author outlines, Russia must unshackle the Soviet Union by voting out the shaky Communist Party and carrying out a major restructuring of the economy. The author added that the Kremlin should liberate Moscow’s former colonial territories, especially the Baltics, the Caucasus, and large parts of Central Asia.

In 1990, as the Soviet Union was moving toward its final collapse, a famous Russian writer sketched out plans for a post-Soviet future. As the author outlines, Russia must unshackle the Soviet Union by voting out the shaky Communist Party and carrying out a major restructuring of the economy. The author added that the Kremlin should liberate Moscow’s former colonial territories, especially the Baltics, the Caucasus, and large parts of Central Asia.

But other borders will be up for grabs. Parts of northern Kazakhstan – areas that, according to the author, were never truly Kazakhstan – should be returned to Russia. The same should be true of Belarus, which was hardly a different state from Russia. Most importantly, parts of Ukraine remained legitimately Russian territory, from eastern Ukraine to Crimea and even Kiev. All these lands constituted traditional Russian territory. The author proposed that all of these should constitute the future “Russian Federation.” Not just the sudden return of millions of ethnic Russians outside the borders of the Russian Federation to their homeland, but the return of Moscow to its rightful place in the world.

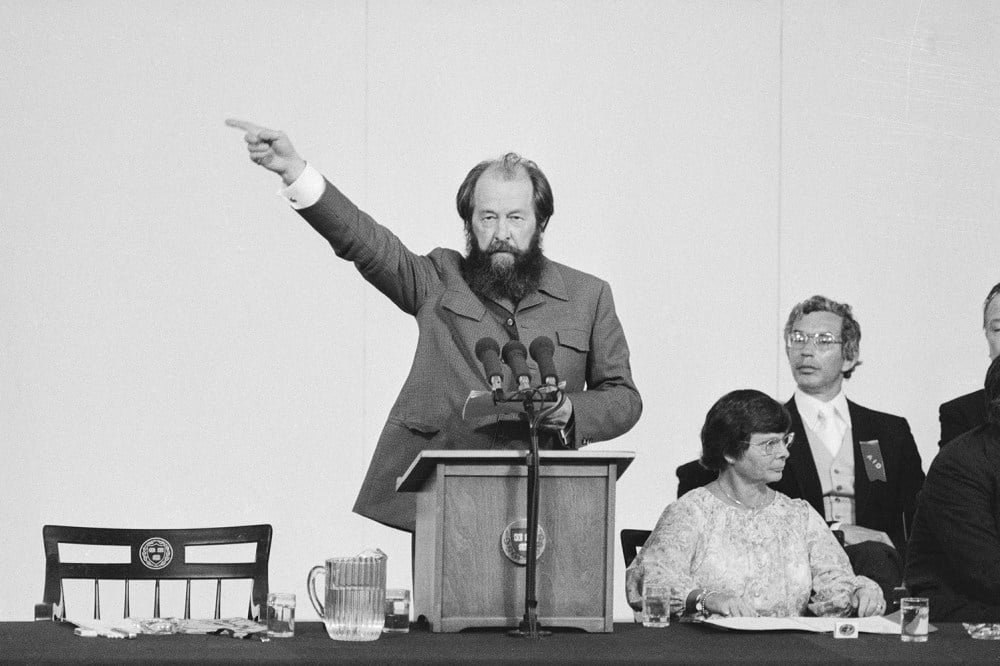

At the time, these policy proposals generated little interest or concern in Western countries. On the one hand, this oversight is understandable given that the Western powers were primarily focused on ensuring a stable collapse of the Soviet Union. But on the other hand, if the author of such a blueprint is rebuilding russiaAlexander Solzhenitsyn was a Nobel Prize-winning author and “the dominant writer of the 20th century.” new yorker Editor David Remnick once said of him:

Many of Solzhenitsyn’s works, especially concentration camp archipelagoThere are also books such as: cancer ward and A day in the life of Ivan Denisovich— is still widely analyzed and debated, rebuilding russia Probably his most overlooked book. And given how closely the Kremlin has followed Solzhenitsyn’s policy recommendations; rebuilding russia Several years have passed since then, and this oversight is even more unfortunate. Especially since this oversight tells us what the Kremlin wants in Ukraine, and by extension, in Ukraine.

The book itself is relatively thin, with an English translation of about 90 pages, more akin to a manifesto than a fully completed manuscript. But even in those pages, Solzhenitsyn is not only a Russian nationalist himself, but someone who dabbles in the kind of intrigue and mysticism that would later saturate Russian President Vladimir Putin. It makes something clear. Like Putin, Solzhenitsyn approvingly quotes Russian fascists like Ivan Ilyin and praises the “spiritual life of the nation.” He also claims that many of the small countries colonized by the Russian military during the imperial era “lived well” in the Russian Empire, but how the Russian military brutalized entire countries in North Asia. , it completely ignores how it stripped population and sovereignty alike, and even stripped it of state power. Genocide. He even writes that countries like Kazakhstan were “linked together in a completely haphazard way”, not just the modern country, but also the former Kazakhstan, which is still considered part of the Russian Federation. It downplays Kazakh historical claims to territory.

But it is in Ukraine, and in Solzhenitsyn’s call for the establishment of the Russian Federation, that Solzhenitsyn’s restorationism shines through and provides insight into the Kremlin’s forces and coming plans. Like many other writers, including figures such as Alexander Pushkin and Joseph Brodsky, Solzhenitsyn infused his writings about Ukraine with unabashed Russian chauvinism. Among topics that would later be taken up by other Russian nationalists, Solzhenitsyn argued that both the “Mongol invasion” and the “colonization of Poland” had torn apart Russians and Ukrainians (as well as Belarusians). , accused him of dividing “our people” into “three factions.” Ignoring centuries of scholarship, Solzhenitsyn said, “All stories about the existence of an independent Ukrainian people from around the 9th century and having their own non-Russian language are recently fabricated lies.” wrote. While previous attempts at Ukrainian independence were elite-led and top-down, taking place “without consulting the entire population,” more modern efforts to create an independent Ukrainian state “required It was nothing more than a campaign to destroy it. [Ukraine] It is a “cruel partition” that will tear “the lives of millions of individuals and families” apart.

Solzhenitsyn wrote that a new organization should stand up to replace Ukraine’s independence from the Russian Federation. “Only the entity called Russia, as it was designated long ago, will remain…or it may be called ‘Russia,’ the name it has used since the 18th century,” he wrote. The situation: “Russian Federation.” ”

Copies of Solzhenitsyn’s books and personal notes.Lasky Diffusion/Getty Images

Rather than writing for the Western audience that had previously admired works exposing Soviet crimes, Solzhenitsyn said: rebuilding russia Together only for the Russian audience. And they ended it quickly.and Approximately 20 million copies printed, Russian readers were hooked on Solzhenitsyn’s call to expand Russia’s borders and restore “the spiritual and material salvation of its own people.” Among those readers was Boris Yeltsin, the soon-to-be president of Russia, who, according to historian Vladislav Zubok, said the book had a “huge influence” on him, and who spoke of Ukrainians and He claimed that Russians were simply “one nation divided by geopolitical disasters and foreigners.” Conquest. “

Solzhenitsyn’s policy proposals also influenced Russia’s other future president, Putin. It is unclear whether Putin has ever read Solzhenitsyn’s work, but it is clear that the current Kremlin chief was a fan of Solzhenitsyn’s policy proposals, especially his nationalism.

It is not difficult to see how Solzhenitsyn became Putin’s “spiritual guru,” as one analyst has written. As Robin Ashenden has pointed out, Solzhenitsyn was not only “an unquestioned Russian nationalist”; rebuilding russia, Solzhenitsyn became increasingly disorganized and descended into the nationalist madness that would later drive President Putin. By the mid-1990s, Solzhenitsyn began to argue that the collapse of the Soviet Union was driven by the United States’ “common purpose” to “use any means possible, whatever the consequences, to weaken Russia.” (Of course, this ignores the fact that the George H.W. Bush administration not only sought to unite the Soviet Union, but also actively pushed back against Ukrainian separatism.) Soon Solzhenitsyn was spouting that Ukraine’s democratic Orange Revolution was just a symptom. NATO’s “Russian Encirclement Plan” and, in fact,[v]”Large areas of land that were not historically part of Ukraine” were “forcibly incorporated into the modern Ukrainian state and the policy of acquiring NATO membership at any cost.”

Years later, Solzhenitsyn’s comments have become almost indistinguishable from Putin’s rhetoric on Ukraine. Like Solzhenitsyn, President Putin considers Ukrainian territories such as Crimea and the so-called Novorossia to be legitimately Russian. Like Solzhenitsyn, Putin believes that ethnic Russians living in Ukraine face “fanatic suppression and persecution of the Russian language.” And like Solzhenitsyn, Putin believed that Russia could not “under any circumstances … abandon our solidarity” with Ukraine’s ethnic Russian population.

It is no wonder, then, that by the 2000s Solzhenitsyn had made it clear that he was a fan of Putin’s policies. Praising Putin’s “resurrection of Russia,” Solzhenitsyn received a state prize for cultural achievements from the Kremlin and was “deployed as part of the Kremlin’s counterrevolutionary strategy.” Tomiwa Owolade writes that the famous writer had become “the unofficial leader of Russian nationalist intellectuals.”

President Putin chats with Solzhenitsyn at his home near Moscow on September 20, 2000. AFP (via Getty Images)

It all culminated in a direct meeting between Putin and Solzhenitsyn just before Solzhenitsyn’s death in 2008. Sitting at a small table between bookshelves, Putin “talked to the ailing writer about the following things.” [Russia’s] future. ” It was, at least in part, the future that Solzhenitsyn had once sought. As President Putin has outlined, he has Many of the policies that he pursued were “generally in harmony with Solzhenitsyn’s writings.”

Russian President Vladimir Putin speaks at the inauguration of Solzhenitsyn’s new monument in Moscow, December 11, 2018. Mikhail Svetlov/Getty Images

It would be an overstatement to say that President Putin has relied solely on Solzhenitsyn’s blueprint to explain his paranoid obsession with Ukraine and the most devastating war Europe has seen in nearly a century. The roots of Russian nationalism are much deeper than any writer and much older than the works of Solzhenitsyn.

But Solzhenitsyn, an unparalleled writer especially in the collapsing Soviet Union, managed to capture the diffuse aspects of Russian nationalism in a way that would be attractive to future Russian leaders and to future Russian revivalists. It is clear that it has been structured. Solzhenitsyn called for, and even tolerated, Russian restitutionism, and in 1990 the coming new imperialism, as well as Russia’s continued and widespread belief in the subordination and essential falsehood of modern independent Ukraine. contributed to the foundation of

Defenders of Solzhenitsyn will point to his writings. rebuilding russia He despised militarism as a means of expanding Russia’s borders. (“Of course, if the people of Ukraine should I sincerely hope No one will try to forcefully detain them in order to separate,” he wrote. ) But even that defense is questionable. Years after Ukrainians in Crimea and Donbass explicitly voted for independence from Moscow, Solzhenitsyn still refused to consider these regions as legitimately Ukrainian. And given that he continued to support President Putin well into his later years, even after the Russian president claimed that Ukraine was “not even a country,” that defense has little credibility.

But even more indefensible is how the West ignored and belittled Solzhenitsyn’s unrepentant nationalism in the post-Soviet period. Western powers, distracted by Solzhenitsyn’s anti-Soviet credentials, missed the contours of the empire the author had painted and how they influenced the Kremlin in the years that followed. Even after President Putin escalated the invasion in 2022, the West, like many other Russian nationalists, turned a blind eye rather than confronting Solzhenitsyn’s revivalism head on. I hoped that the flames that fueled such views would die out on their own. .

But more than 30 years have passed since Solzhenitsyn first called for membership in the Russian Federation, and the flame shows little sign of extinguishing anytime soon. In fact, President Putin continues to push further and further into the abyss that Solzhenitsyn first laid out, and shows no signs of stopping. That is why Solzhenitsyn’s strategy, and Putin’s willingness to follow it, must be seen exactly as such. It is an unmitigated threat to European stability and to the very idea of the Ukrainian (and by extension Belarusian and Kazakh) statehood. Solzhenitsyn did not live to see the return of the Russian Federation, but it is not because Putin did not try, it is also because of the sacrifices of Ukrainians themselves that we did not.